Illicit Influence: Part One

In the spring of 2016, as the Russian-domiciled First Czech Russian Bank (FCRB) approached insolvency, staff worked feverishly to erase ledgers, destroy documents, and conceal evidence of the bank’s activity over the previous 9 years.

These documents, had they survived, would have revealed the details of a litany of questionable activities: financial support for Iran; use of the bank as a vehicle for money laundering by corrupt elites on a massive scale through the Russian Laudromat, a money laundering scheme identified by Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP); support for sanctioned organized crime figures; and most alarming of all, Russian state-sanctioned interference in the Western political system in the form of a 9.4 million euro loan to the National Front, a far-right French political party.

Executive Summary #

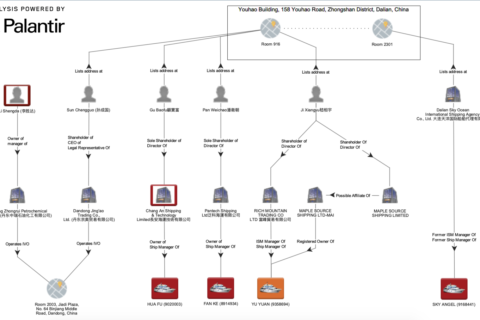

In the spring of 2016, as the Russian-domiciled First Czech Russian Bank (FCRB) approached insolvency, staff worked feverishly to erase ledgers, destroy documents, and conceal evidence of the bank’s activity over the previous 9 years. These documents, had they survived, would have revealed the details of a litany of questionable activities: financial support for Iran; use of the bank as a vehicle for money laundering by corrupt elites on a massive scale through the Russian Laudromat, a money laundering scheme identified by Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP); support for sanctioned organized crime figures; and most alarming of all, Russian state-sanctioned interference in the Western political system in the form of a 9.4 million euro loan to the National Front, a far-right French political party.1 While most documents attesting to these activities were destroyed,2 a more banal form of illicit activity—self-enrichment by the bank’s director—caused litigation over remaining assets and liabilities. Information released in that litigation offered investigators a rare glimpse into how a private Russian bank became a key cog in Moscow’s attempt to swing political contests overseas—and how this bank sought to use existing campaign finance loopholes to achieve political objectives.

In light of recent electoral interference posed by Russian public and private actors, US and European law enforcement have intensified scrutiny of Russian financial support for foreign political actors in Western political systems. Despite this attention, relatively few instances of direct Russian financial interference in the political processes of other countries have been reported in the media. It is thus imperative to carefully study the known instances of Russian financial support for foreign political actors in order to identify the nodes and pathways facilitating these financial flows. Of these few instances, the FCRB’s 9.4 million euro loan to the National Front is perhaps the best known. The loan, unlike many other instances of Russian political finance, was channeled through formal financial mechanisms, rather than opaque or criminal pathways. But while the funding of the National Front did not involve sophisticated money laundering or outright bribery, the use of a private bank nonetheless provided a layer of deniability, shielding the involvement of senior Russian government officials who had helped to arrange the loan.