The Handasieh Network

On April 6, 2018, a sunny day in Douma, Syria, bombs began falling from the sky, assaulting the city indiscriminately. The attack continued into the next day, when chemical weapons were dropped on the city’s citizens, over 500 of whom were brought to medical facilities with symptoms of exposure to a chemical agent. At least 43 people died as a result of this exposure.

Hundreds of chemical attacks like this one have taken place on Syrian soil since the beginning of the civil war there. The Global Public Policy Institute has attributed two percent of these attacks to the Islamic State and 98 percent to the Syrian government under the leadership of President Bashar al-Assad. The attacks carried out by the Assad regime have used chemical weapons such as chlorine and sarin, and they have resulted in the death and injury of thousands of Syrian citizens.

These persistent attacks raise the question of how a regime under such a heavy international sanctions regime can acquire the supplies needed to manufacture chemical weapons. Although some of the necessary chemicals and equipment may be available within Syria, other elements, such as specific chemical precursors or corrosion-resistant construction materials, must be sourced from abroad. The Syrian Scientific Studies and Research Center, also known as the SSRC, is the government body that oversees the production of Syria’s chemical weapons, including the import of chemical precursors and other materials. The United States government has identified and sanctioned Syrian and foreign companies used by the SSRC to procure such materials. By examining these companies, their broader corporate networks, and their current and former activities, we can identify possible routes for continued procurement of materials that support the Syrian chemical weapons program.

The Handasieh Network #

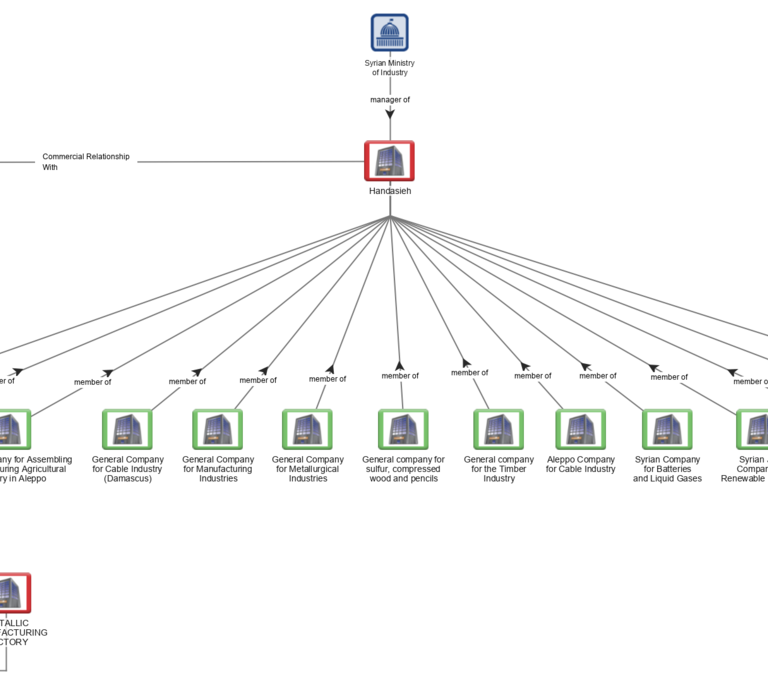

One good example is Syria’s General Organization for Engineering Industries, a sprawling state-owned conglomerate under the authority of the Syrian Ministry of Industry that supervises public companies active in the construction and industrial sectors. Also known as Handasieh, the organization was sanctioned by the US Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) on July 18, 2012 for “acting for or on behalf of Syria’s SSRC” and “contribut[ing] materially to the proliferation of WMD or the means of their delivery.” But Handasieh is more than just one Syrian company – there are at least fourteen subsidiaries operating directly under it that produce everything from steel to renewable energy to pencils. If these companies are 50% or more owned by Handasieh, they too are legally sanctioned under OFAC’s current regulations. However, only one of Handasieh’s direct subsidiaries, the Syrian Arab Electronic Industries Company (Syronics), has been explicitly sanctioned by OFAC, while two additional entities that share identifiers with one of Handasieh’s subsidiaries have also been sanctioned.

These unsanctioned subsidiaries represent possible avenues for sanctions evasion and chemical weapons procurement. By examining corporate and trade records associated with these entities, we can conclude that they may be acting in coordination with Handasieh (and thus potentially with the SSRC), and that foreign procurement activity continues through them. This foreign procurement activity may coincide with the procurement of chemical precursors or other materials the Assad regime needs to launch attacks like the one on April 7.

Convergence and Coordination #

Handasieh’s connections with its subsidiaries don’t end at the level of corporate affiliation: public records show that different companies in the Handasieh network can be tied together through their common use of identifiers like addresses, websites, and email addresses. For example, the General Company for Steel and Steel Products lists “www.handasieh.org” as its website on a public tender for zinc, while a profile for the General Company for Cable Industry in Damascus lists Handasieh’s primary email address as a point of contact. On public tenders, the General Company for Cable Industry in Damascus has used an email address associated with another Handasieh subsidiary, the Aleppo Company for Cable Industry. Such shared identifiers were common throughout tenders appearing in the names of Handasieh subsidiaries, indicating a high likelihood of coordination between the companies in the wider Handasieh network.

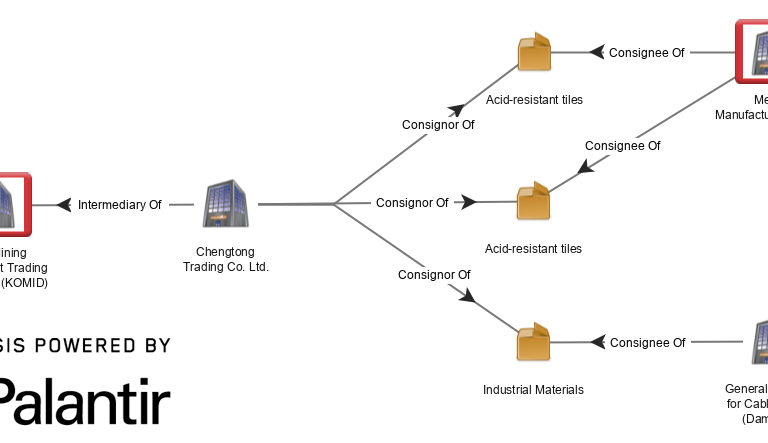

A series of three shipments from North Korea to Syria illustrates the point. In its March 2018 report, the UN Panel of Experts for North Korea indicated that the General Company for Cable Industry was the intended consignee of a 2016 shipment of industrial materials sent to Syria from North Korea. This shipment was part of a batch of five shipments sent from North Korea to Syria. Two of the shipments were sent to the Metallic Manufacturing Factory, an OFAC-sanctioned company that is connected with another Handasieh subsidiary, the Company of Metallic Constructions and Mechanical Industries. These shipments contained “acid-resistant tiles, adhesive paste, and accessories,” materials which, according to a UN Member State, could “be used to build bricks for the interior walls of [a] chemical factory.” Not only does the network appear to be integrated, with members using identifiers associated with Handasieh and other Handasieh subsidiaries, but it appears to be coordinating activity among both sanctioned and unsanctioned nodes in the network, highlighting the risk of complex evasion schemes.

Procurement Abroad #

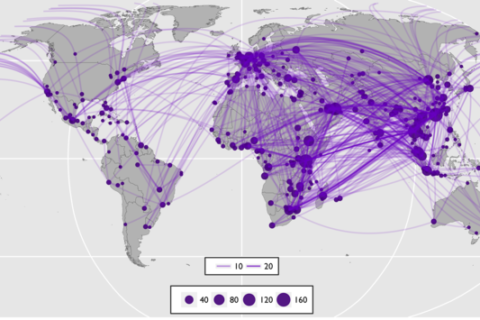

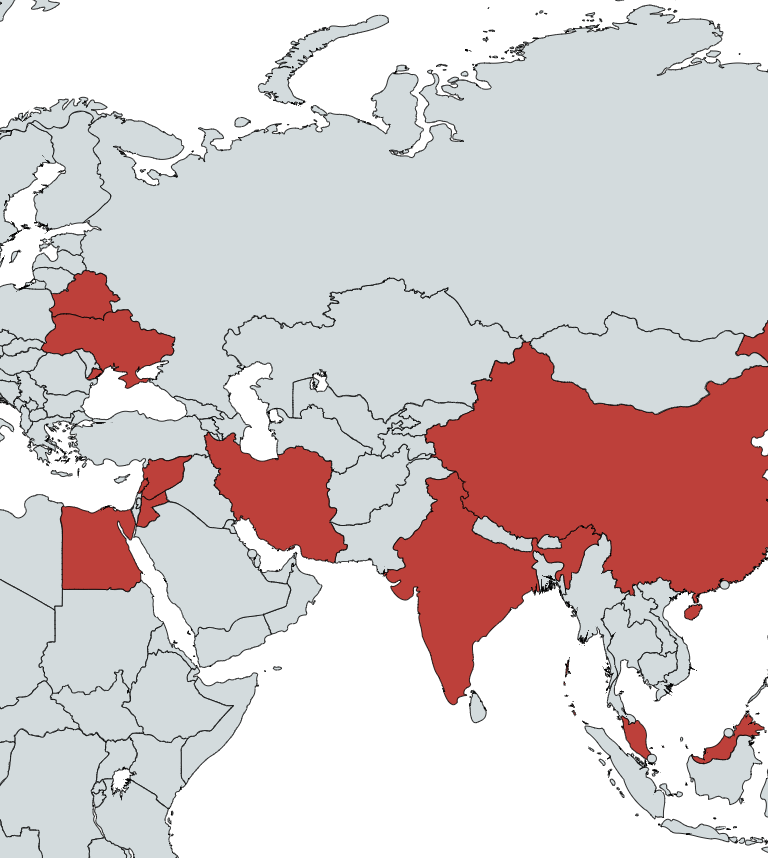

Tenders, trade data, and other public material can provide a wealth of information about procurement pathways used by the Handasieh network (and therefore possibly the SSRC). Many of the companies associated with Handasieh have public tenders posted on their websites, Facebook pages, or on the websites of Syrian foreign affairs offices around the world. While tenders are of course helpful in identifying what a company is looking for, they are also helpful in identifying where the company is seeking to procure its materials from. For example, Syronics, the OFAC-sanctioned Handasieh subsidiary, has had tenders posted by the Syrian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in both Egypt and Lebanon. Trade data can also shine a light on the countries from which these companies are sourcing. Commercial trade data indicates that the Handasieh-linked General Company for Iron and Steel Products has received at least 39 shipments of industrial parts and equipment from Apollo International Limited, an Indian company. Sometimes making connections between these companies and foreign countries is even easier: one of Handasieh’s subsidiaries is the “Syrian-Ukrainian Joint Company for the Production of Photovoltaic Pumps.” To date, we have identified thirteen countries (Belarus, China, Egypt, France, Germany, India, Iran, Jordan, Lebanon, Malaysia, North Korea, South Korea, and Ukraine) from which Handasieh subsidiaries have procured, are procuring, or have attempted to procure materials after OFAC sanctioned Handasieh in 2012.

Much of the procurement that we can see in the open source, whether through tenders or trade data or international agreements, may be perfectly licit, and destined for civilian engineering projects across Syria. We do not assert that any entity mentioned in this blog post knowingly contravened any international law or treaty. However, the pathways that licit products take can also be used to procure the materials the Syrian government needs for its chemical weapons program. Given the known procurement of materials by Handasieh (and some of its subsidiaries) on behalf of the SSRC, the interconnected nature of the companies in the Handasieh network, and the illicit procurement on the part of non-sanctioned entities in the network, all Handasieh subsidiaries and the methods through which are worth a second look by the international community, law enforcement, and civil society.

Austin Bodetti contributed in the research and investigation for this blog post.