Illicit Influence: Part Two

This case study goes beyond well-known instances of coercive Russian hydrocarbon diplomacy to examine how energy dominance is paired with deceptive corporate and financial obfuscation to undermine Western democracy, enrich elites, and achieve political ends.

Executive Summary #

Russia has a long history of using its control over European energy supplies to achieve political aims, and this “energy weapon” has become famous as a blunt instrument. According to the dominant image of Russia’s energy diplomacy, if states diverge from Russian foreign policy aims, the gas will be cut off in the dead of winter—as it was in Ukraine.

But in reality, the energy weapon is much more subtle, and much more effective at undermining Western states. The Russian government has learned to use energy to cultivate politically important relationships in consumer countries. At the same time, Russia uses its tools of asymmetric influence, including political interference and disinformation, in furtherance of its energy goals. This multi-faceted toolkit gives Russian policymakers more avenues to pursue their policy aims in the West, something missed when Russia’s energy diplomacy is thought of exclusively in terms of gas and oil cutoffs.

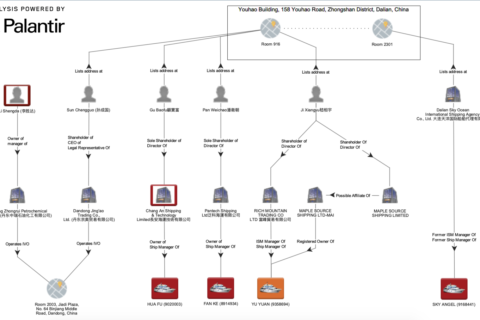

This case study goes beyond well-known instances of coercive Russian hydrocarbon diplomacy to examine how energy dominance is paired with deceptive corporate and financial obfuscation to undermine Western democracy, enrich elites, and achieve political ends. Examining case studies from several European countries, it highlights three relevant typologies that show how Russian energy politics go beyond pipeline power to include financial and other malfeasance:

- The use of energy delivery intermediaries, often based in Switzerland, to enrich favored elites in consumer countries;

- Russian use of energy firms to conduct political financing designed to influence the political affairs of consumer countries; and

- The pursuit of politically driven energy decisions in the fields of natural gas and nuclear power.

The aim of these tactics is to gain political leverage, often indirectly or through intermediaries and cutouts, in order to build long-term influence. Although they are easier to miss than crude gas cutoffs, energy-based relationships are arguably more important, as they create durable favorable constituencies, corrode democratic politics, and tie European countries to inefficient energy suppliers for the long run.