Imported War

Every tool of war tells a story. For South Sudan, a country with no domestic weapons manufacturing and ongoing civil conflict, every weapon reflects international intermediaries and middle men that profit from procurement. In the fall of 2014, amidst ongoing civil war with the Sudan People’s Liberation Army in-Opposition (SPLA-IO), the government of South Sudan purchased Russian-made amphibious vehicles (AMVs). With the purchase of these AMVs, the government forces acquired a unique degree of mobility to maneuver in wetlands, extending the reach of their attacks, including deliberate attacks directed at civilians.

Imported War: South Sudan’s Russian AMVs and the Role of Al Cardinal #

Every tool of war tells a story. For South Sudan, a country with no domestic weapons manufacturing and ongoing civil conflict, every weapon reflects international intermediaries and middle men that profit from procurement.

In fall of 2014, amidst ongoing civil war with the Sudan People’s Liberation Army in-Opposition (SPLA-IO), the government of South Sudan purchased Russian-made amphibious vehicles (AMVs). With the purchase of these AMVs, the government forces acquired a unique degree of mobility to maneuver in wetlands, extending the reach of their attacks, including deliberate attacks directed at civilians.

Using publicly available information, we traced these AMVs from their manufacturer in Russia to a Kenyan port, and ultimately to several assaults directed at civilians during fighting in South Sudan. According to records reviewed by C4ADS, a key player in the procurement of the AMVs was a UAE-registered company owned by a Sudanese businessman named Ashraf Seed Ahmed Ali Hussein (commonly referred to as Al Cardinal). Based on previously publicized cases reviewed by C4ADS, between 2015 and 2018 Al Cardinal has potentially profited from up to $832 million in government payments and contracts with the Government of South Sudan (GOSS).

Despite fluctuations in fighting and international attempts to cut off arms transfers into South Sudan such as the July 2018 UN Arms Embargo, intermediaries such as Al Cardinal have remained constant. As long as such intermediaries maintain access to the global financial system, perpetrators of violence in South Sudan will be able to procure the tools necessary to wage war.

From Russia to South Sudan #

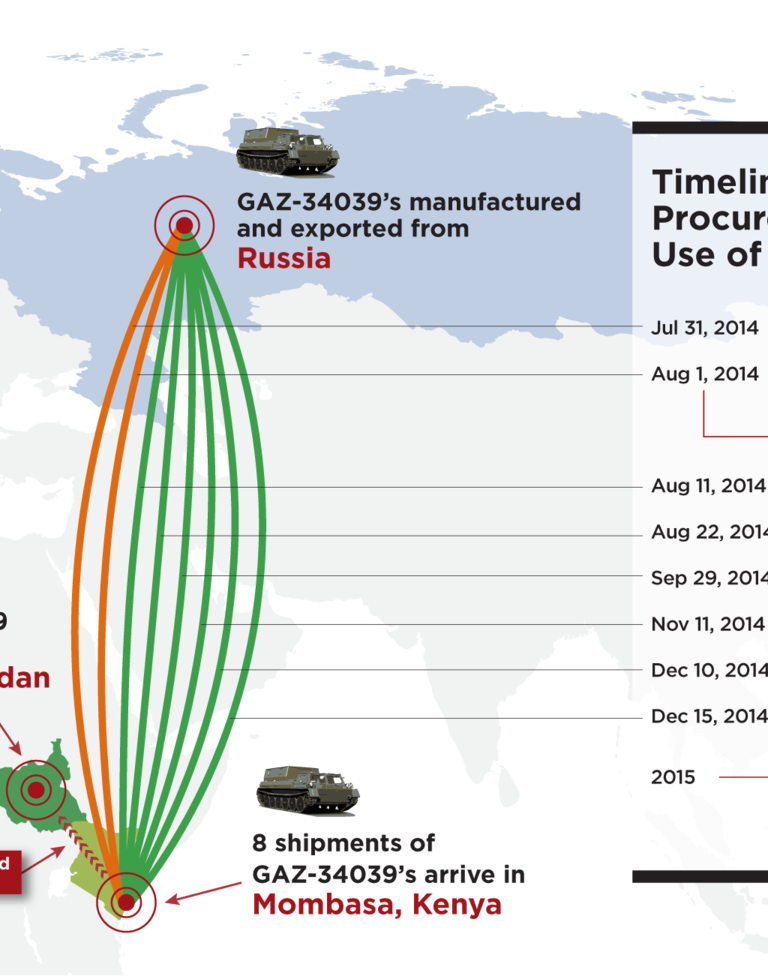

By examining imagery, corporate records and trade data, we followed the AMVs from Russia through Kenya and ultimately to South Sudan.

On August 1, 2014, nearly eight months after civil war began in South Sudan, the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) announced that they had purchased 10 AMVs. These vehicles are capable of traversing both dry and water-logged terrain, giving the SPLA the ability to maneuver areas of South Sudan like the Sudd (a vast wetland). This allows the SPLA to pursue rival armed groups, as well as civilians, into previously inaccessible swamps and wetlands.

Soon after the SPLA announced its purchase, evidence of the AMVs was published by the United Nations Panel of Experts on South Sudan (UNPOE) in its August 2015 report. The images published by the UNPOE show AMVs in Upper Nile State. Analyzing the social media of SPLA-affiliated individuals, we identified at least four different Facebook accounts that posted additional images of AMVs between 2015 and 2018.

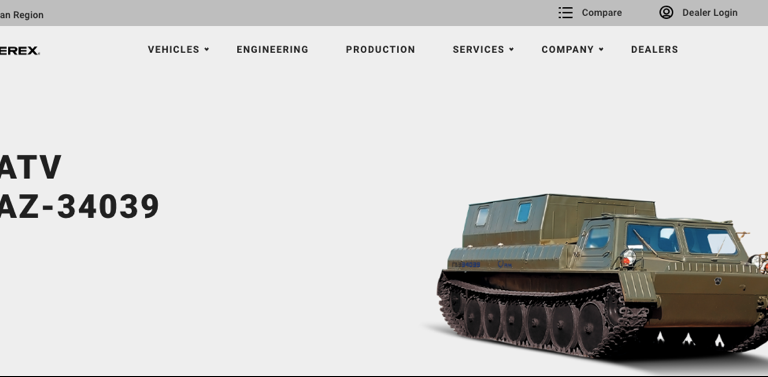

The August 2015 report published by the UNPOE confirmed that the AMVs operating in South Sudan were the GAZ – 34039. The GAZ – 34039 is a model manufactured by only one Russian company: the Zavolzkhsky Crawler Vehicle Plant (ЗАВОЛЖСКИЙ ЗАВОД ГУСЕНИЧНЫХ ТЯГАЧЕЙ), a subsidiary of RM-Terex, a joint venture between Russia’s state-owned Russian Machines and the Terex Corporation.

For a GAZ-34039 to reach a landlocked country like South Sudan, it would usually need to transit through a third country on its route from Russia; this would force the shipment to travel through visible points in its way to South Sudan, including sea ports or border crossings where trade data is aggregated by customs officials. To better understand the GAZ-34039’s global route, we examined publicly available trade data of Zavolzkhsky’s exports to East Africa.

In the months leading up to AMVs appearing in South Sudan, Import Genius records[1] show that Zavolzkhsky made eight shipments to East Africa. All of these shipments were exported to Kenya’s port of Mombasa. The recipients of the shipments were listed in trade data as South Sudan’s Ministry of Interior (MOI) and a company named Green for Logistics LLC.

Every one of these eight shipments listed GAZ-34039s and/or related GAZ parts in the shipment description. According to Import Genius records, The Ministry of Interior of South Sudan received two shipments in a two-day span (July 31-August 1, 2014) while Green for Logistics LLC received 6 shipments across 4 months (August 11 – December 15, 2014). The shipments from Zavolzkhsky bear several similarities beyond the timing of their delivery: at least two shipments report identical weights, product descriptions, and quantities. Interestingly, after the first direct purchase by the Ministry of Interior, all subsequent purchases were conducted through a private company called Green for Logistics LLC.

Al Cardinal – South Sudan’s Sudanese “Swiss Army Knife” #

Green for Logistics LLC is a private Dubai-based company, which reports from credit information bureau Cedar Rose (held by author) show is 39% owned by Sudanese commercial magnate Ashraf Seed Ahmed Ali Hussein (Al Cardinal).

Dubbed the “Swiss Army Knife” of the Government of South Sudan (GOSS) by Africa Intelligence, Al Cardinal has faced accusations of orchestrating corruption schemes with actors at the highest level of South Sudanese politics for at least 12 years (prior to South Sudan’s independence). C4ADS has reviewed media reports and documents which allege that Al Cardinal or companies allegedly affiliated with him have received up to $832 million USD of payments or alleged procurement contracts from the government of South Sudan between 2015 and 2018.

A prolific businessman, Al Cardinal reportedly has investments in the agricultural, shipping, sports, automotive, finance, petroleum and healthcare sectors ranging from the US, the UAE (documents held by author), and the UK to Ethiopia, Egypt, Sudan, and South Sudan (documents held by author). He is frequently mentioned in media reporting for his alleged role in suspected money laundering during the Kiir presidency, including:

- Receiving a contract for 3,133,208 barrels of oil from the South Sudanese Ministry of Petroleum and Mining in 2017 (documents held by author)

- Receiving $30,000,000 from the Ministry of Petroleum in May 2018

- Receiving $299,614,428 from the Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning on July 25, 2018

- Received $250,000,000 for brokering a deal between Sudan and South Sudan

On multiple occasions, Al Cardinal has been accused of significantly overvaluing vehicles in sales to the GOSS:

- In early 2007, Al Cardinal was arrested in Juba in relation to a government procurement scandal. The South Sudanese government purchased 450 Toyota Land Cruisers from an Al Cardinal Group branch located in Saudi Arabia for $95,000 each, even though they had a market value of $50,000. As of August 2019, only 153 of the 450 cars have been delivered.

- In June, 2015, local media reports surfaced that President Kiir had purchased 1,000 tractors from Al Cardinal Group for donation to the Ministry of Agriculture. It was later discovered that these tractors were bought using government funds and not from Kiir’s own pocket as originally reported. It was further discovered that these tractors, with market value of $27,000 per vehicle, were purchased by GOSS for $50,000 per vehicle.

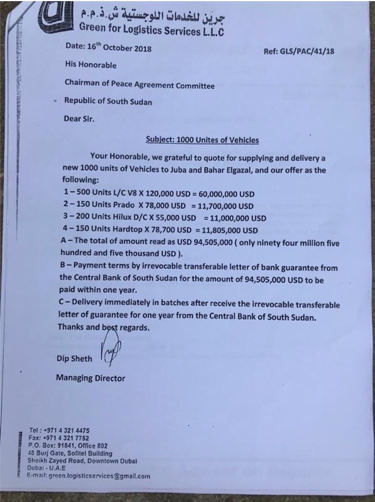

- Al Cardinal’s name surfaced once again in fall 2018 in relation to vehicle procurement, this time along with Green for Logistics LLC. Documents surfaced on Twitter and confirmed by Africa Intelligence detailed Green for Logistics LLC’s bid to supply South Sudan with $94 million in Toyota Land Cruisers and other vehicles. This suggests that Al Cardinal continues to play a role as an intermediary in contracts with the Government of South Sudan.

VIOLENCE DIRECTED TOWARDS CIVILIANS

In both 2015 and 2018, AMVs were used for attacks against civilians fleeing violence. In places like the Sudd, where other tracked and armored vehicles have struggled, AMVs gave the SPLA a unique capability to extend offenses that included violence directed towards civilians.

According to the UNPOE for South Sudan, between April and June 2015, the SPLA used AMVs to carry attacks “into the swamps of the Sudd, where civilians fleeing violence had sought refuge.” This was part of the offensive of Unity State, in which deliberate attacks on civilians by government forces contributed to substantial civilian displacement. Victims interviewed by Human Rights Watch claimed the AMVs were a critical component of the Unity Offensive, as they were used to follow fleeing civilians “into very wet swampy areas where they hid as they tried to flee attacks.”

Despite international outrage, the AMV’s role in terrorizing civilians has continued. As recently as July 2018, Amnesty International has continued to publish information on the use of amphibious vehicles to “hunt down civilians who fled to nearby swamps.” Survivors that spoke with Amnesty International described how “groups of five or more soldiers swept through the vegetation in search of people, often shooting indiscriminately into the reeds. ”

Ultimately, the tools of violence and war in South Sudan rely upon a network of companies, ports, brokers, and politicians. Individuals such as Al Cardinal with sophisticated logistical capabilities are critical to providing instigators of violence with the tools needed to wage war – but facilitators such as Al Cardinal are still dependent on access to international financial and commercial systems. Limiting that access in support of the UN Arms Embargo can help disrupt the supply chain of violence in South Sudan.