Crowdsourcing

In Kazakhstan, one environmental conservation organization has developed an innovative approach to preserve one of the region’s most unique yet critically endangered species.

Saiga tartarica (saiga for short) is a species of antelope that has inhabited Eurasia for over 100,000 years. Adult saiga typically stand between two and three feet tall at the shoulder, and adult males have ribbed horns that grow to between eleven and fifteen inches. But the saiga’s most remarkable feature is undoubtedly its snout. The peculiar appendage allows the saiga to filter dust from the air and regulate its body temperature.

In Kazakhstan, one environmental conservation organization has developed an innovative approach to preserve one of the region’s most unique yet critically endangered species.

Saiga tartarica (saiga for short) is a species of antelope that has inhabited Eurasia for over 100,000 years. Adult saiga typically stand between two and three feet tall at the shoulder, and adult males have ribbed horns that grow to between eleven and fifteen inches. But the saiga’s most remarkable feature is undoubtedly its snout. The peculiar appendage allows the saiga to filter dust from the air and regulate its body temperature.

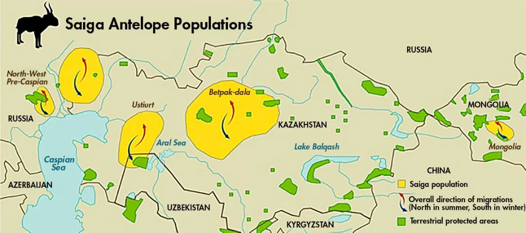

While once abundant and widespread, with 1.25 million saiga worldwide as recently as 1981, the species has suffered a catastrophic decline, decreasing to only 24,000 in 2004. Current estimates place today’s saiga population at around 165,600, with the remaining herds found in pockets of Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Russia, and Mongolia.

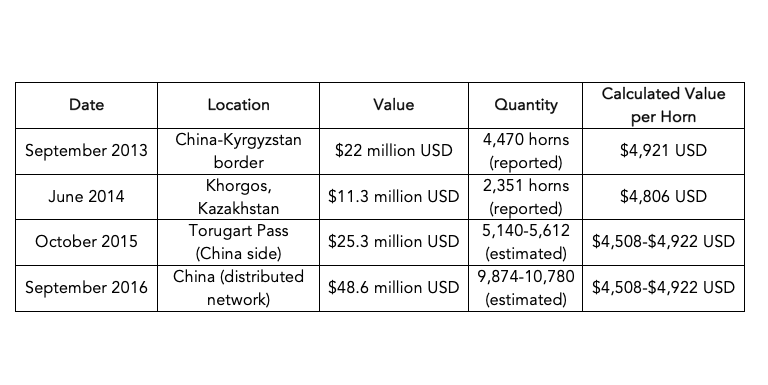

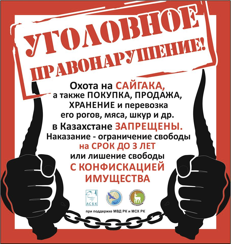

Poaching is one of the principal causes of the saiga’s drastic population decline in recent years. According to traditional Chinese medicine, saiga horn is believed to have medicinal properties that can regulate “internal heat” (“清热”). The horn is typically crushed, dissolved, and sold as “cooling water.” While trafficking in saiga horn is nominally illegal under the CITES convention, enforcement is lax and the trade is relatively open. In Kazakhstan, traders will even post flyers soliciting the horns, complete with a phone number or an email address.

The Association for the Conservation of Biodiversity in Kazakhstan (Казахстанская ассоциация сохранении биоразнообразия, or ACBK for short) has a unique approach to tackling the issue of saiga poaching and horn trafficking. ACBK runs an annual campaign in partnership with the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the Committee on Forestry and Fauna to combat the domestic trade of saiga horns. The goals are twofold: 1) raise awareness of the illegal nature of saiga horn trafficking, and 2) create a database of names and phone numbers associated with traffickers. These goals are achieved through a crowdsourced targeting of the flyers plastered across the country.

The most recently completed campaign wrapped up on January 21, 2017. As of February 26, ACBK’s pages on Facebook and VKontakte had 686 combined subscribers who contributed 92 photos. Twenty-one unique phone numbers were identified, spread across nine cities. Additionally, nineteen websites were identified as hosting posts for saiga horn. ACBK contacted the websites and requested that they take down the posts. Eleven websites complied, five did not reply, and three were defunct upon a follow-up check. While ACBK has not mentioned any resulting arrests or seizures, it has said that all the collected information has been transferred to the environmental police to assist in investigations.

This campaign is a low cost, effective approach to wildlife conservation. Organizing via social media allows for collaboration among disparate actors and crowdsourcing allows for the assiduous efforts of small-scale environmental organizations to be amplified by hundreds of local residents. While conventional anti-trafficking measures by law enforcement and NGOs hamper poaching operations and the flows of illicit wildlife products, they offer little opportunity for local participation. Contributions, regardless of size, give local volunteers ownership and investment in the outcome. In the long term, crowdsourcing campaigns such as ACBK’s may catalyze a shift in societal attitudes towards wildlife trafficking.