Something Smells Fishy…

Combating illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing is inherently a big data challenge. Billions of Automatic Identification System (AIS) and Vessel Monitoring System (VMS) messages from tens of thousands of active vessels must be sorted and examined to find the few vessels that are likely to be committing illicit activity. On top of that, data visibility problems plague current monitoring systems, with AIS (which can “go dark” at the captain’s discretion) and VMS (which is largely unavailable to the public) both failing to provide the full picture of at-sea activity. In addition to the limitations that exist within these systems, only the largest fishing vessels are likely to carry AIS, and VMS adoption is dependent on coastal states requiring the system. The result is that the picture of maritime activity produced by AIS and VMS requires careful curating and additional analysis before conclusions can be drawn. Spotting these kinds of gaps in the huge amount of data collected can be difficult, but is necessary to identify many types of illicit activity.

With such a vast ocean of data to sift through, effective targeting requires focusing on chokepoints. For IUU fishing, the clearest chokepoint is the logistical vessels that support fishing vessels’ clandestine activities. For instance, “reefer” or refrigerated cargo vessels are critical facilitators that help deep sea fishing fleets regularly offload their catch and take on supplies while at sea, thereby allowing them to stay at sea for much longer periods of time than would otherwise be possible. Reefers service entire fleets, serving as a critical link bringing seafood— both licit and illicit—to shore. These reefers are far fewer in number than fishing vessels, and are much more likely to regularly transmit AIS signals, making them a visible data point that analysts can exploit.

C4ADS’ partnership with Windward enables us to use this type of data in our analysis. Using Windward’s maritime risk analytics platform, C4ADS is able to access structured several years’ worth of historical data on vessel operations. The platform is easily filtered according to customizable search queries, allowing tailored, hypothesis-driven analysis of specific questions.

C4ADS analysts have recently been using these queries to uncover IUU trends through analysis of risky vessel behavior. Some examples of risk indicators include:

- “Drifting” – Windward uses this term to denote vessel movement under 3 knots, which is the usual speed at which two adjacent vessels would travel to transfer goods, catch, or crew.

- High Risk Zones – Windward allows analysts to define zones where suspicious activity, such as ship-to-ship transfers, IUU fishing, or sanctions violation, commonly occurs.

- Flags of Convenience (FOC) – Vessels engaging in illicit activity often use flags of convenience as a means of obfuscating their ownership or avoiding legal action or scrutiny. FOCs are a means of circumventing regulatory oversight with little to no barrier to entry.

- “Meetings” – Windward applies machine-learning algorithms to detect anomalous ship activities, including meetings between vessels at sea, for extended periods of time. Vessels that “meet” for extended periods of time are more likely to be refueling at sea or transferring catch, crew, and/or supplies (known as transshipment), potentially in violation of law.

As an example, we will walk through a case in which Windward tools helped C4ADS analysts hone in on suspicious vessel activity and then map the corporate network behind three refrigerated cargo vessels.

From Activities… #

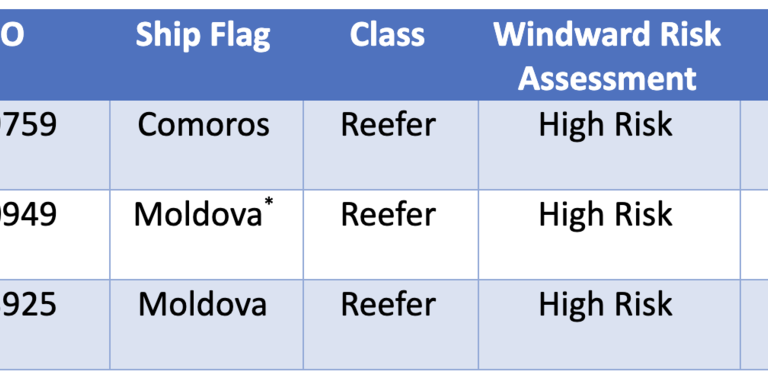

Using the above set of risk indicators, we identified three reefers operating in and around the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) of Guinea Bissau, Guinea, and Ivory Coast:

All three vessels are flagged to FOCs (Comoros and Moldova). According to their historical AIS transmissions, they consistently behave in the following ways:

- Drifting while at sea for periods ranging from under one hour to multiple days

- Changing port of destination and draft after drifting at sea

- Drifting near areas where fishing vessels from the same corporate fleet operate.

These behaviors are common for vessels that are transshipping, but do not necessarily indicate illicit activity. However, when this activity is observed in a particular high-risk zone, such as the EEZ of Guinea Bissau— where at-sea transshipment has been banned since 2015— this behavior warrants further scrutiny.

…To Insights… #

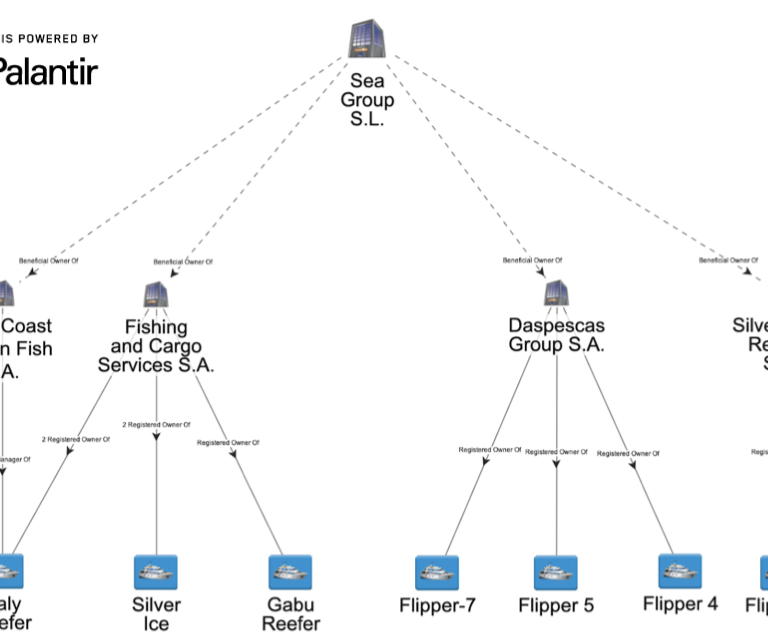

All three vessels, along with at least four other trawlers, are registered to several Panama-domiciled companies, which are all ultimately controlled by Sea Group SL, a company incorporated in the Canary Islands. The Panama connection is a red flag for our analysts, as the country has frequently been criticized by experts as a haven for tax evasion, money laundering, and other illicit activity.

Vessels in Sea Group SL’s fleet have also been implicated in risky activity. For example, in 2014, the GABU REEFER was fined US$2,000 by Liberia for landing fish without the necessary authorizations. Then in 2015, the SILVER ICE was categorized as a high-risk vessel by the West Africa Task Force (WATF) after the government of Comoros raised concerns about the vessel’s activity in the region. While it is unclear what activity directly incited those concerns, the SILVER ICE was documented landing catch sourced from Guinea Bissau and Guinea in numerous ports in West Africa at the time.

Inquiries into the SILVER ICE were also in part due to pressure from the European Union for Comoros to increase oversight of distant water fishing vessels registered under their flag. Flag registration in Comoros is reportedly controlled by the Administration of the Union of Comoros and is an open registry. This means that in Comoros, foreign companies are able to register vessels without proving a “genuine link” to the country and oversight is outsourced to private interests.

Finally, in 2017, the SALY REEFER was caught carrying out an illegal transshipment with three other ships in the EEZ of Guinea Bissau. The owners and crew members reportedly faced fines and legal action as a result of the illegal transshipment.

…To Action. #

Ultimately, fully understanding illicit maritime activity requires going from sea to shore. A vessel is just an asset owned by an onshore network, and its activity at sea is ultimately determined by the financial interests of its beneficial owners. C4ADS therefore believes effective maritime analysis requires both at-sea and onshore analysis to connect vessel behavior to corporate networks.

C4ADS’ Natural Resources Cell is committed to using these and other methods to combat IUU fishing. Windward’s technology is a critical part of this effort, helping our analysts identify high-risk activities at sea that can be tied to on-shore corporate networks. Directing this information to the right authorities can then result in real action—like arrests, seizures, and ship detentions—that have a tangible effect on the overall trade in illicit fish products.