Poison Pathways

In Peru, the use of mercury in illegal gold mining has poisoned tens of thousands of people and created a public health and environmental crisis. This investigation shows how illicit actors may be abusing Peru’s attempts to regulate the deadly chemical. Peru attempts to regulate mercury through a registry of authorized users. But by cross-referencing the registry with a national database of mining concessions, we found that many people with mercury access had long histories of illegal mining allegations. We also found that individuals linked to Peru’s main mercury importer may be illicitly marketing mercury to unauthorized third-party buyers. Some of these individuals wield considerable power in local politics, casting doubt on Peru’s control on the trade and distribution of this deadly chemical. What we uncovered call into question the seriousness of Peru’s commitments under the UN Minamata Convention on Mercury, a global environmental treaty, to limit the use of mercury in illegal mining.

Lee esto en español

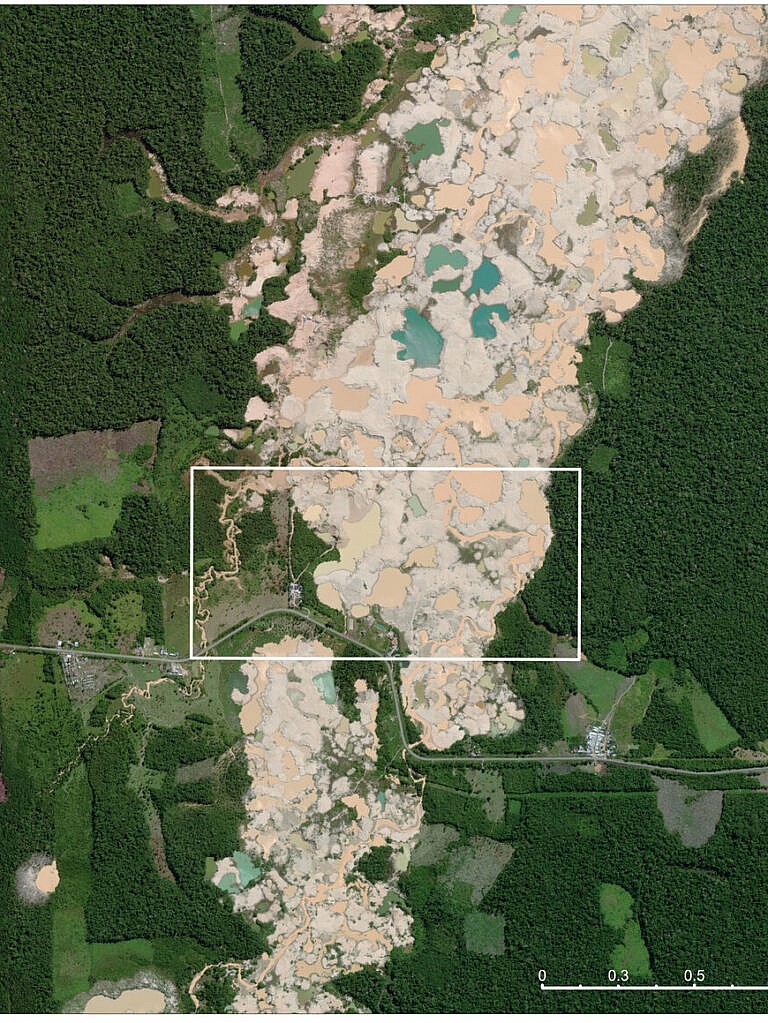

Peru is the largest producer of gold in Latin America and the sixth largest in the world. According to the Global Initiative Against Transnational Crime, as much as 28% of the country’s gold is extracted illegally: in 2013, illegal gold mining in Peru was valued at $2.6 billion. This form of extraction often relies on artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASGM) operations, which present grave threats to human security and the environment due to rampant deforestation, minimal safety protocols, and the unregulated use of mercury.

Despite its devastating effects on the environment and public health, mercury is widely used in ASGM to amalgamate and extract gold from sediment and ore. Unregulated mercury use in gold mining has poisoned tens of thousands of Peruvian citizens, and poses a particular threat to indigenous communities whose livelihoods are linked to the rivers of the Amazon basin. This dependence on mercury presents an opportunity for investigators, however, to trace the commercial networks that fuel illegal gold mining Peru.

Drawing on government records, trade data, social media, and local reporting, C4ADS examined Peru’s trade in mercury. Although Peru’s National Customs and Revenue Authority (SUNAT) aims to control the use of mercury in gold mining through a special registry of authorized mercury users, C4ADS found evidence that individuals affiliated with the country’s main mercury importer, Triveño Mining Company del Peru S.A.C., may market its mercury to unauthorized third-party buyers in spite of a ban on such transactions. C4ADS also found several entities on the list of licensed mercury users with documented histories of alleged illegal mining, casting into doubt the strength of Peru’s enforcement of controls on the trade and distribution of this deadly chemical.

Follow the Mercury #

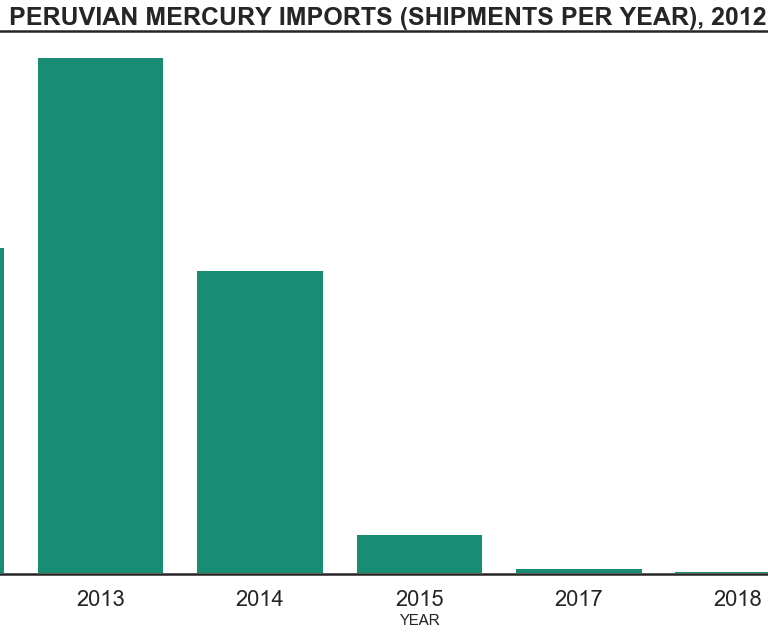

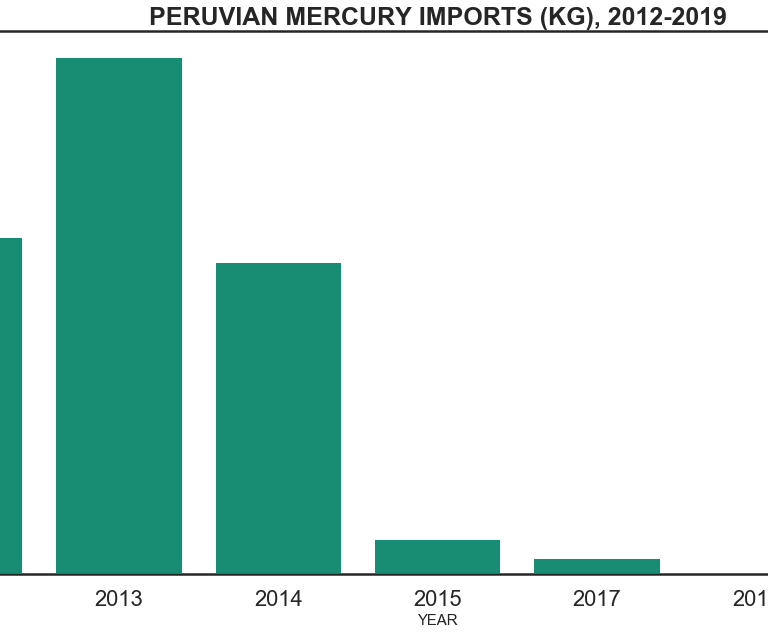

Trade data shows that Peru has reduced imports of mercury substantially since its 2015 ratification of the UN Minamata Convention, a global treaty designed to protect human health and the environment from the adverse effects of mercury. After peaking at 155 in 2013, annual shipments of mercury declined to just one shipment in 2018. In 2019, after four years of decline, the number of shipments increased to ten.

A similar trend is reflected in the total weight of mercury imports from 2012 to 2019. After peaking at 188,383 kilograms in 2013, the volume of mercury imports declined to just 40 kilograms in 2018. In 2019, however, that figure rose to 9,061 kilograms.

Just as interesting as the quantity of imports are the people and companies that allegedly received them. According to trade data, of the ten mercury imports recorded in 2019, nine went to Triveño Mining Company del Peru S.A.C., adding up to a combined net weight of 2,181 kilograms. According to an archived copy of its website, Triveño Mining Company forms part of the Grupo Triveño, a consortium with interests in logistics, mining, and other sectors. Customs records from Veritrade show that the company’s most recent shipment occurred in December 2019. All nine of its 2019 shipments were imported from Mexico, the world’s second biggest mercury producer after China.

Grupo Triveño has a history of reported involvement in illicit mercury trade. Its president and CEO, Adolfo Triveño Torres, was convicted of trafficking in mercury for illegal mining in 2016. According to a court document, Triveño Torres sold small containers of mercury labeled “Mercurio Rey Español Triveño” from a store in the Puerto Maldonado, which serves as a logistical hub for miners in the region of Madre de Dios, a gold-rich region in the Amazon basin bordering Bolivia and Brazil. Triveño Mining Company has nonetheless remained on SUNAT’s list of authorized mercury users and resumed importing mercury in 2019.

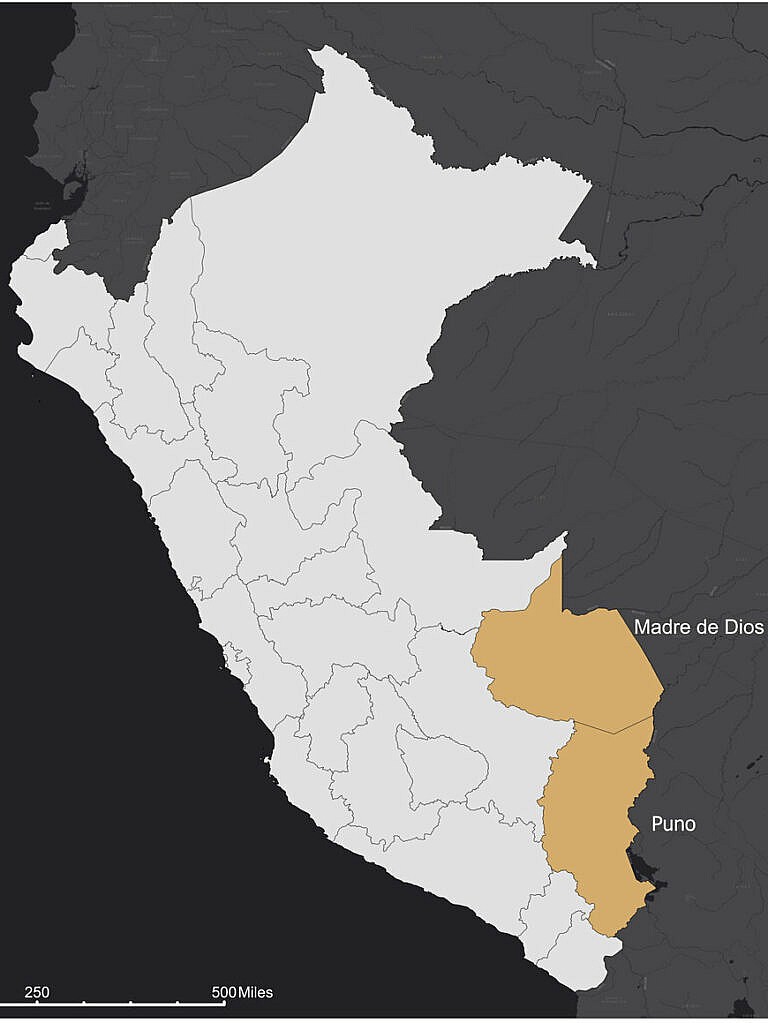

Mercury resale appears to have continued through 2019. It is illegal to sell mercury to buyers without SUNAT authorization, but a post in the Facebook group “Avisos Clasificados (Puno – Juliaca)” advertising wholesale and retail mercury in 34.5 kg bottles suggests that at least part of the Triveño Mining Company’s supply may still be passed on to unauthorized third-party buyers. The Facebook user’s LinkedIn profile states that since 2013, the account owner has been employed by Grupo Triveño at its branch in the mining hub of Juliaca, Puno, a department on Peru’s southern border with Bolivia. In October 2019, Peruvian authorities seized 200 kilograms of mercury allegedly intended for use in illegal mining from a store in Juliaca, which public records show is owned by Triveño Mining Company. Since January 2020, no new imports of mercury have been recorded in Peruvian customs data, according to Veritrade.

Mercury Users and Mining Concessions in Peru #

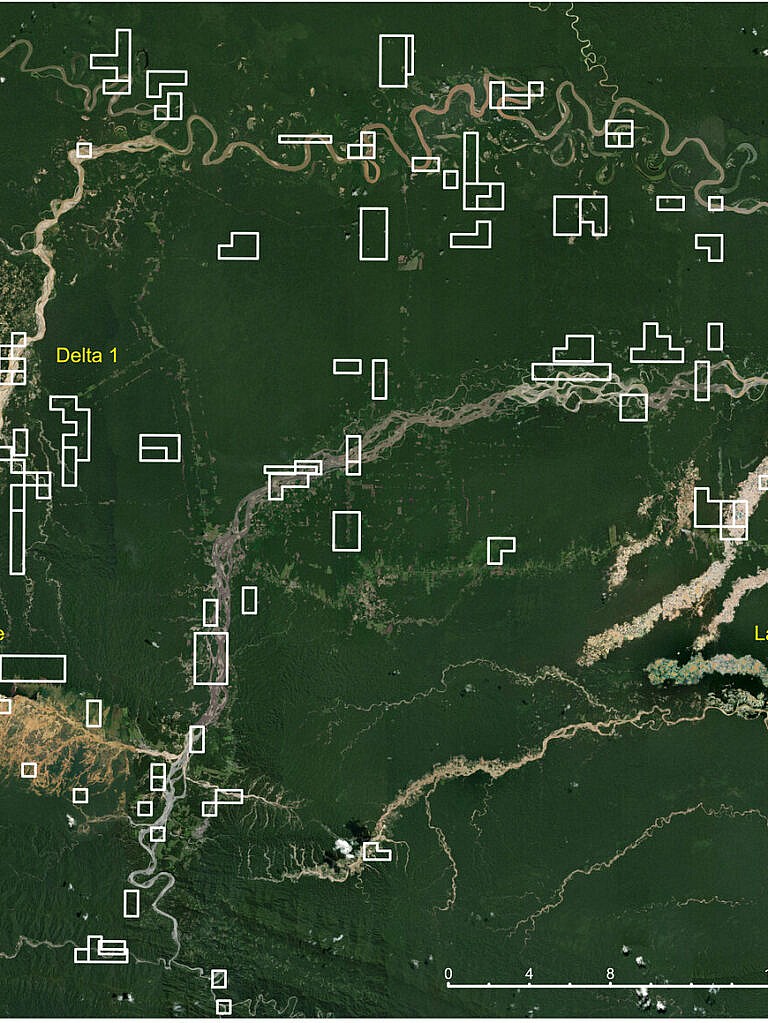

Grupo Triveño is not the only mercury importer that may be engaging in illicit activity. To get a better sense of the scale of the mercury trade, C4ADS combined SUNAT’s list of authorized mercury users with a database of mining concession titles from Peru’s Ministry of Energy and Mines (MINEM) to map out mining concessions controlled by authorized mercury users. Of the 173 names on SUNAT’s list of authorized mercury users, 102 also appear as title holders of mining concessions. While not on its own an indicator of illegal activity, the joint holding of a mercury use license and a mining concession caused us to dig further. In total, 1,728 mining concessions covering 1,101,269 hectares (2,721,295 acres) are owned by people or businesses authorized to use mercury. The majority of these concessions are owned by a handful of large companies: Compañia de Minas Buenaventura S.A.A. (649 concessions), Union Andina de Cementos S.A.A. (255 concessions), Minera Barrick Misquichilca S.A. (164 concessions), Minsur S.A. (161 concessions), and Minera Yanacocha S.R.L. (77 concessions).

Of the 102 authorized mercury users who also appear as title holders of mining concessions, 75 are located in Madre de Dios. Across the region, they hold a total of 170 mining concessions covering 46,221 hectares (114,215 acres). 78% of these concessions in Madre de Dios are held by individuals, compared to just 8.6% of concessions nationwide. This disparity reflects the prevalence of ASGM in Madre de Dios, which is driven by networks of individual people rather than large corporations. As with large-scale mining, however, the control of critical inputs and infrastructure in the region’s mining economy tends to accumulate in the hands of a powerful few.

Among the authorized mercury users with concessions in Madre de Dios are several individuals with histories of alleged involvement in illegal mining, pointing to potential weaknesses in SUNAT’s enforcement of Peru’s controls over the deadly chemical and calling into question the seriousness of its commitments under the Minamata Convention.

One such individual is Eugelio Amado Romero Rodriguez, also known by his nickname “Comeoro,” a former member of congress (2011-2016) and former director of the Mining Federation of Madre de Dios (FEDEMIN). Romero Rodriguez also ran for governor of Madre de Dios in 2018. In December 2011, he was suspended from Congress for 120 days after a federal investigation revealed that he permitted illegal miners to work on his concessions in exchange for payments in gold. In 2012, he was reportedly a principal organizer of demonstrations that drew over 30,000 miners against new regulations on informal mining; he later introduced legislation aimed at overturning the laws. According to official records, Romero Rodriguez holds three active concessions in Madre de Dios: Tres de Agosto I, Sol de Mayo, and Taliban.

Yony Baca Casas, who holds three active concessions, also appears on the list of authorized mercury users. Baca Casas, a member of one of the region’s most powerful mining families, was the president of the Miners’ Association of Huepetuhe as of 2018, which represents one of the largest mining camps in Madre de Dios. The Baca Casas family has been subject to numerous denunciations, investigations, and efforts at state sanction since at least 2000. Because the family members are viewed by Peruvian authorities as coordinating their activities as a single economic unit, federal authorities consider their business too large to qualify as artisanal mining and instead treat it as a medium to large-scale enterprise. The Ministry of Energy and Mines blocked the family from undergoing a process to formalize its operations that was initiated in 2012 for those who truly qualify as artisanal miners. In 2012, the Ministry of Interior issued a statement denouncing members of the Baca Casas family for money laundering. The following year, the Ministry of Environment initiated proceedings against the family and its companies for illegal mining. Despite—or perhaps because of—the family’s economic activities, however, it has become an influential local political force: Yony’s father served as the mayor of Huepetuhe, and Yony herself participated in talks between local miners and former president Pedro Pablo Kuczynski.

SUNAT’s list of authorized mercury users not only points to the political clout of illicit mining networks, but also to the informal power structures within Peru’s gold mining economy. Two men accused of running Madre de Dios’s illegal gold mining organizations—Celso Quispe Chipana and Leonardo Huaman Huanca—also appear on the list of mercury-authorized concession holders, Quispe Chipana with three active concessions and Huaman Huanca with two. A 2012 article published in La República named the two men among the “gold barons” behind illegal mining in Madre de Dios. Both were alleged to control numerous mining operations; Huaman Huanca also allegedly owned several properties and fuel stations along the Interoceanic Highway. Quispe Chipana was sentenced to prison for illegal mining in 2014.

In addition to local political figures and power brokers, the owners of mining, transportation, and construction companies also appear on SUNAT’s list of mercury users. Among these, Francisco Quintano Mendez is one of the most surprising names to surface. Although he only holds one active concession in his name, Quintano Mendez’s company Minerales del Sur (Minersur) was one of Peru’s largest gold exporters until 2018. That year, SUNAT itself began investigating the company for links to illegal mining and money laundering. Minersur’s sole international client, Swiss refinery Metalor, which has processed an estimated 106 tons of gold worth $3.5 billion from Minersur since 2001, suspended imports from the company in early 2018.

Mercury Smuggling from Bolivia #

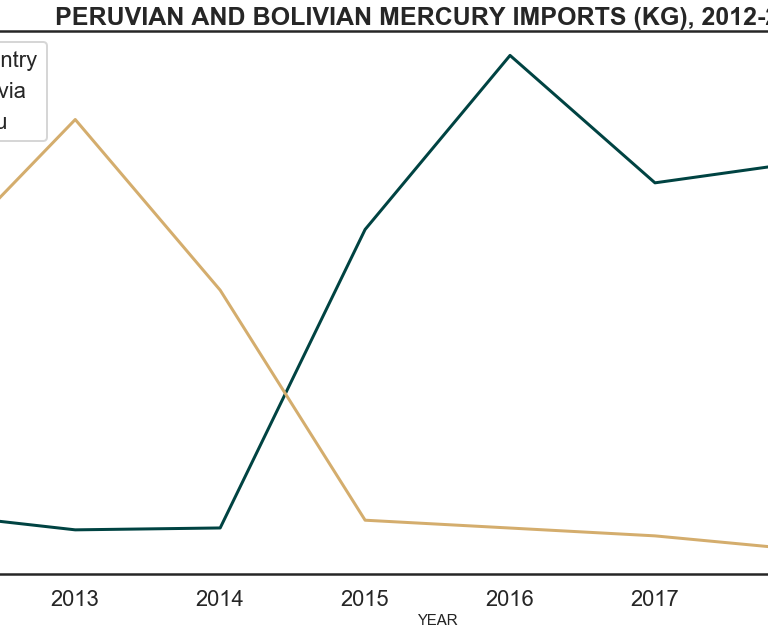

While some of the mercury used in ASGM in Peru is sourced overtly, a great deal is smuggled into the country under the radar. Although the country largely stopped importing mercury in 2015, police seizures and trade data suggest that illicit supply chains have arisen along Peru’s southern border with Bolivia, where mercury imports skyrocketed from 9,514 kilograms in 2014 to 216,454 kilograms in 2016. In 2015, Peruvian authorities seized over a ton of illegally smuggled mercury in the border region of Puno. In a separate incident in 2019, customs authorities in Puno confiscated 110 liters of mercury shipped from Bolivia. Other reports indicate that smaller quantities of the substance are smuggled across the border in suitcases by passengers on commercial buses.

Moving Beyond “Operation Mercury” #

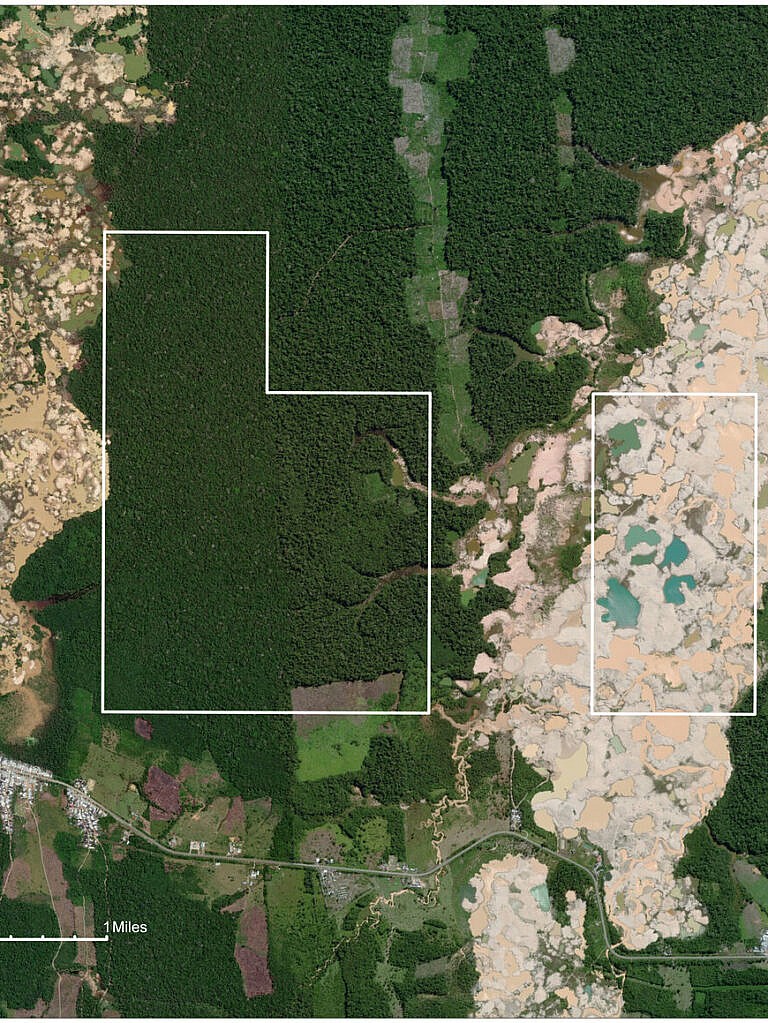

In February 2019, Peruvian authorities initiated “Operation Mercury 2019”—a sweeping crackdown on illegal mining in Madre de Dios that witnessed the installation of military bases and monitoring programs in the region’s most affected areas. In the intervening months, the operation has succeeded in halting the most pernicious environmental effects of illegal gold mining. An August 2019 analysis by Monitoring of the Andean Amazon Project, which tracks deforestation trends in the Amazon basin, found that deforestation in monitored areas had dropped by 92 percent.

To succeed in regulating illegal mining over the long term, however, Peru must couple strong local enforcement with rigorous oversight of mining supply chains. This not only requires that Peru enhance controls within its borders, but also that it strengthen cooperation with its neighbors. Like Peru, Bolivia has ratified the Minamata Convention, but its quantity of mercury imports in recent years indicates a lack of meaningful action towards meeting its international commitments. Peru must work closely with Bolivia to exchange information, build enforcement capacity, and ensure that illicit transnational supply chains do not fill the void left by domestic importers.

Although Peru has attempted to regulate mercury supply chains through a national registry of authorized users, some of these very users have been repeatedly accused of violating laws that aim to counteract the toxic effects of mercury in illegal gold mining. In several cases, these same individuals wield considerable power in local political federations and government institutions, further complicating national efforts at meaningful regulation. In July 2019, SUNAT issued new guidelines that relax the requirements necessary to register as an authorized mercury user—which, judging by current standards, suggests that the threat of unregulated mercury use in Peru’s illegal gold mines is far from resolved.