Against the Grain

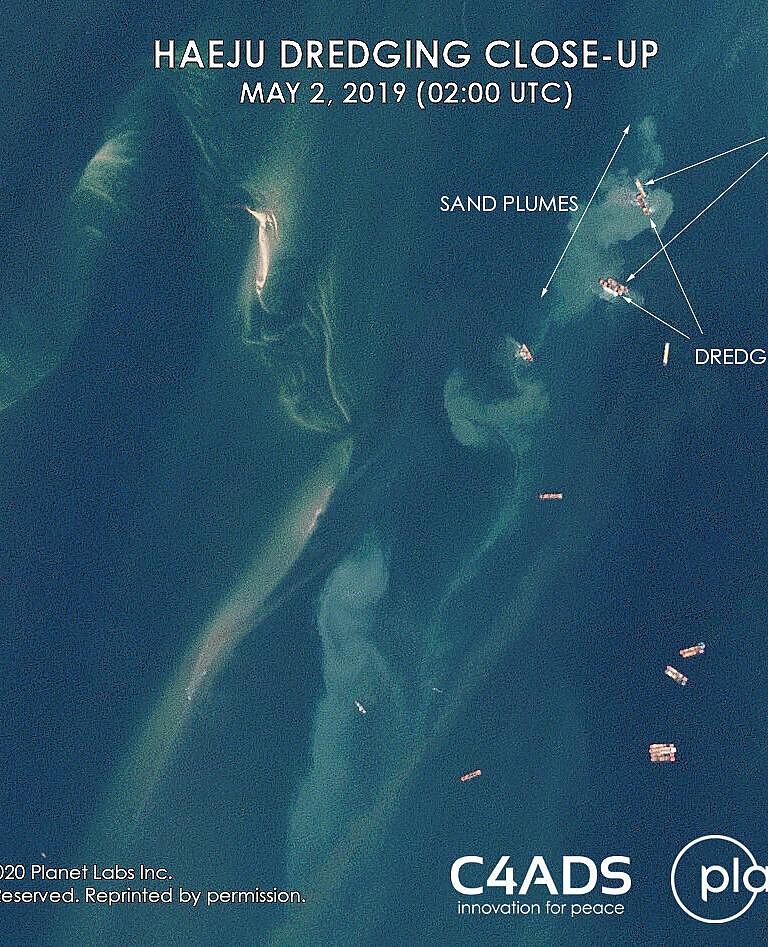

In the early afternoon of May 16, 2019, the normally quiet waters of Haeju Bay, North Korea could have been mistaken for a bustling, international port like Shanghai or Singapore. Less than 30 kilometers from the South Korean island of Yeonpyeong, satellite imagery showed 112 ships dotting the blue-green bay. But their intended cargo was not packed in a container or piled at Haeju Port, it was deep underwater. Among the crowd of ships in Haeju Bay, at least half a dozen dredgers — specialized vessels outfitted with excavation equipment — scraped tons of sand from the seafloor, stirring up tan-colored plumes that streaked across the surface of the water. Barges positioned themselves along either side of a dredger as sand flowed from the dredger’s chute into the barge’s open cargo holds. Once loaded, the barges departed Haeju Bay for various destinations in China.

This blog post is an introduction to and summary of preliminary findings of a C4ADS project investigating sand dredging in Haeju, North Korea.

In the early afternoon of May 16, 2019, the normally quiet waters of Haeju Bay, North Korea could have been mistaken for a bustling, international port like Shanghai or Singapore. Less than 30 kilometers from the South Korean island of Yeonpyeong, satellite imagery showed 112 ships dotting the blue-green bay. But their intended cargo was not packed in a container or piled at Haeju Port—it was deep underwater. Among the crowd of ships in Haeju Bay, at least half a dozen dredgers—specialized vessels outfitted with excavation equipment—scraped tons of sand from the seafloor, stirring up tan-colored plumes that streaked across the surface of the water. Barges positioned themselves along either side of a dredger as sand flowed from the dredger’s chute into the barge’s open cargo holds. Once loaded, the barges departed Haeju Bay for various destinations in China.

What happened on May 16, 2019 was not an isolated incident. Between March and August 2019, Haeju Bay appeared to be the center of a series of large-scale sand dredging operations. Using satellite imagery and Automatic Identification System (AIS) data, C4ADS tracked hundreds of vessels we suspect were dredging sand in Haeju Bay before transporting it to China. This sand extraction from North Korea to China violates United Nations Security Council (UNSC) Resolution 2397 (2017). More than that, the activity in Haeju demonstrates scale, and a level of sophistication unlike other known cases of North Korean sanctions evasion at sea, providing renewed evidence of the DPRK’s evolving abilities to coordinate and execute complex operations with facilitators abroad.

The DPRK and Sand #

Sand is a critical material with various uses in modern infrastructure, such as concrete and glass in construction, and silicon chips in electronics. Although it is the world’s most extracted natural resource today, its demand greatly outstrips supply. As the price of sand has risen rapidly in recent years, so has the practice of both licit and illicit sand excavation and trade around the world.

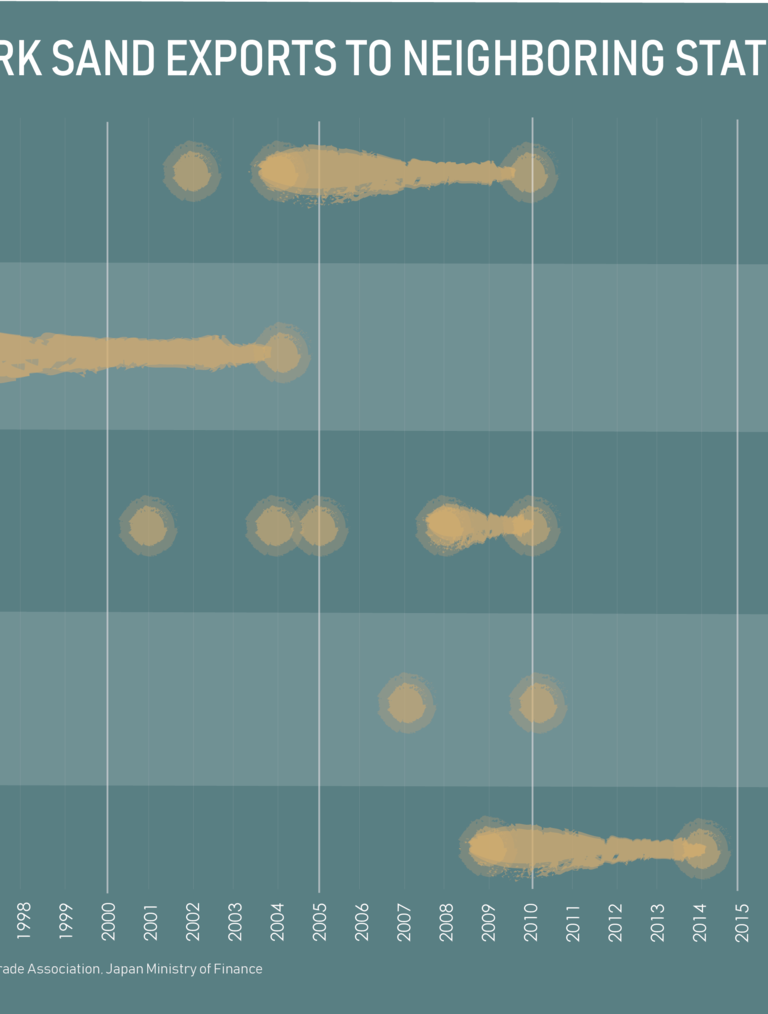

Sand as an export commodity is not new for the DPRK, which started trading sand in the 1990s. Between 1991 and 2017, the DPRK’s neighbors, such as Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, China, and Russia, have periodically imported sand from North Korea. However, in December 2017, UNSC Resolution 2397 imposed a sectoral ban on “earth and stone (HS Code 25).” The resolution prohibits the DPRK from supplying, selling, or transferring sand, directly or indirectly, from its territory or by its nationals or using its flag vessels or aircraft.

However, publicly available information (PAI) suggests that the sale of DPRK-origin sand is ongoing. In August 2019, Daily NK reported on a $3 million contract between Chinese and DPRK entities to dredge sand from the Chongchon river area. This article, as well as other examples in Chinese-language PAI, point to continued sand trade between the DPRK and China in 2019. We will be looking at dredging in Haeju Bay as a major component of this trade.

What Happened in Haeju? #

Between March and August 2019, C4ADS observed a large fleet of vessels originating from Chinese waters travelling to North Korea to dredge and transport sand from Haeju Bay. Using satellite imagery from Planet Labs and AIS data from the Windward maritime analytics platform, C4ADS identified at least 279 AIS profiles that likely participated in these dredging activities in Haeju Bay.

A SPIKE IN AIS ACTIVITY NEAR HAEJU, NORTH KOREA

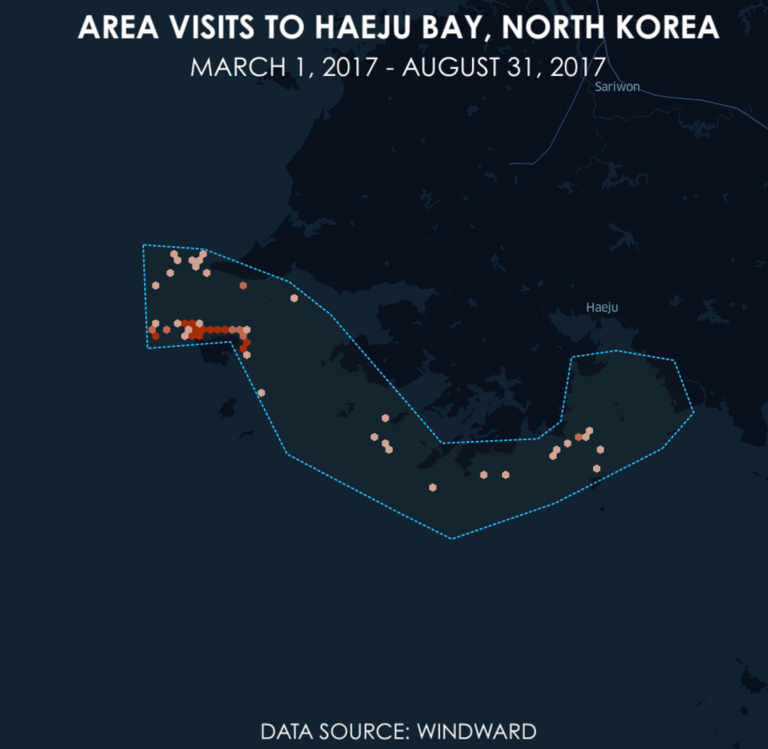

Beginning in March 2019, we observed a significant increase in the number of AIS transmissions in or around Haeju Bay. Foreign vessels rarely transmit AIS data near the North Korean coastline to avoid scrutiny from sanctions monitors. When dozens of ships began appearing near Haeju, the spike in AIS traffic caught our attention.

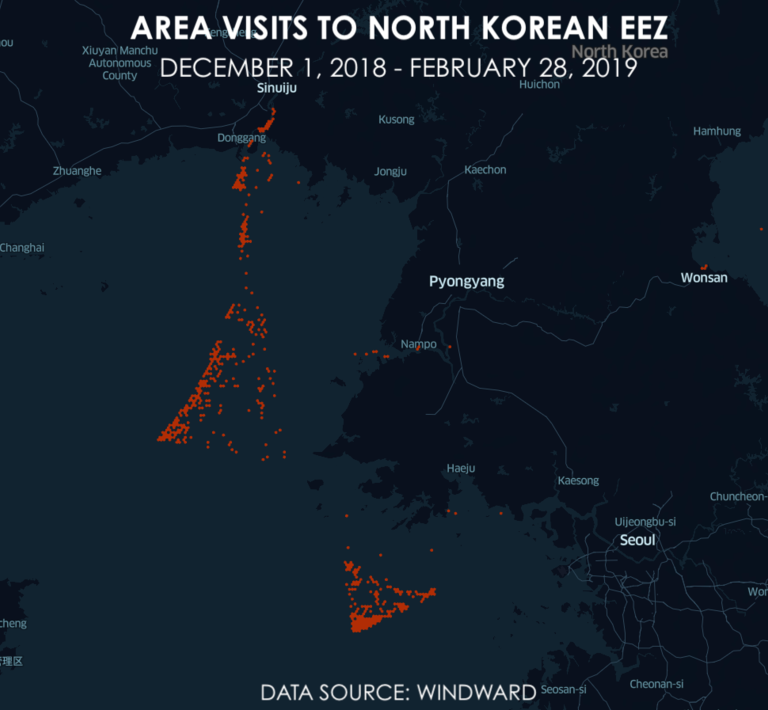

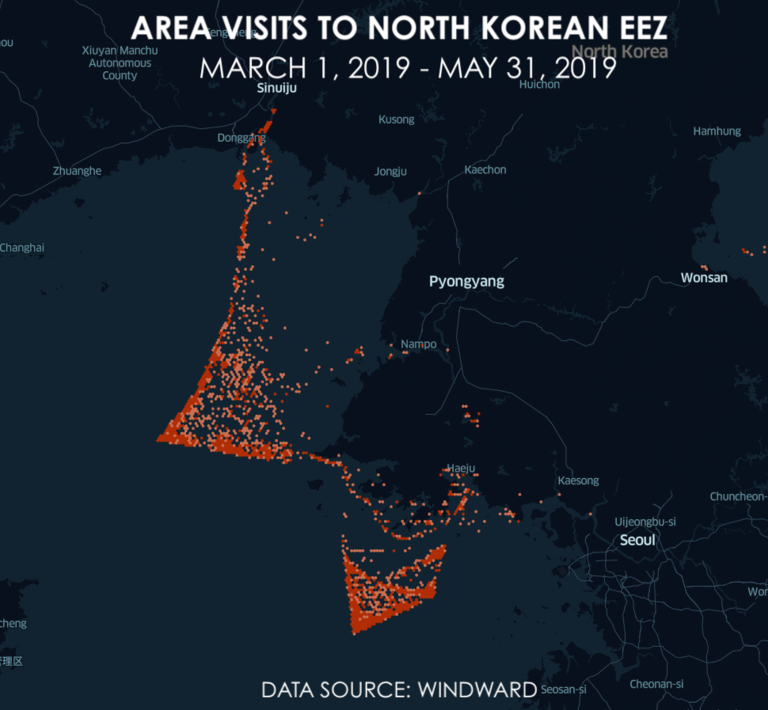

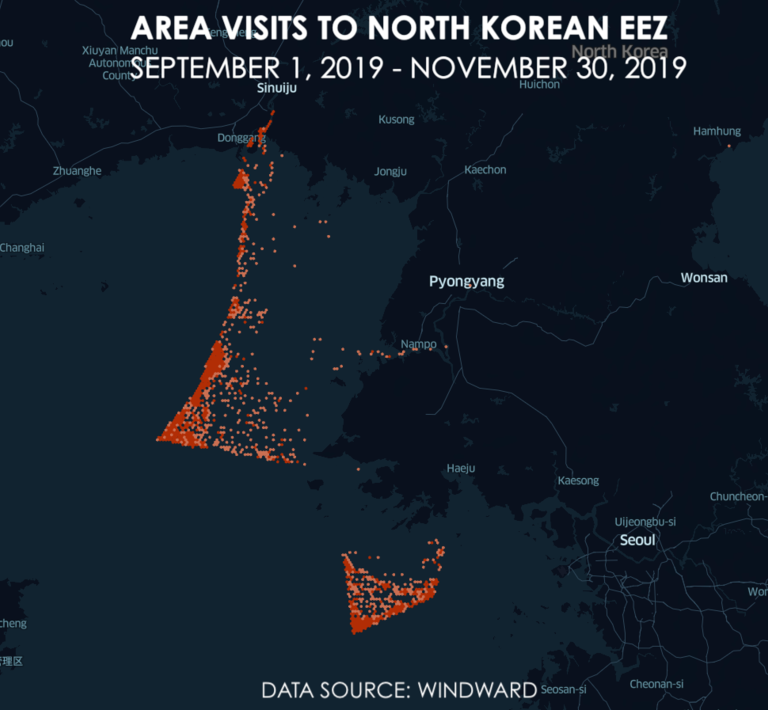

To contextualize the activities in Haeju, we used Kepler.gl, an open source geospatial analysis platform, to visualize AIS transmission patterns in the North Korean Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) during the months before, during, and after the dredging activities. We plotted the locations where vessels entered the North Korean EEZ in three-month periods between December 1, 2018 and November 30, 2019. The data show little to no AIS transmissions in or around Haeju until the beginning of March. The activity picks up quickly in April, peaks in May, and tapers into August.

According to AIS data, the increase in vessel traffic near Haeju during the months between March and August does not appear to be a seasonal phenomenon. Windward records only 418 area visits in the waters in and around Haeju during the same months in 2017 and 2018 combined, compared to 1,563 in 2019 alone.

By looking deeper into these transmissions, we amassed a likely candidate list of 279 AIS profiles—the “Haeju fleet”—that we determined were likely to be involved in this unusual maritime activity in Haeju Bay. It is important to understand that the potential manipulation of AIS, as well as identity reconciliation errors, can result in discrepancies between the number of AIS profiles and actual vessels present in a given location. However, AIS profiles, especially when combined with satellite imagery, offer the most effective proxy for analyzing the overall scale and trends of vessel activity in Haeju Bay.

What We Found #

Satellite imagery from Planet Labs between March and August 2019 provides visual evidence of the vessels engaging in sand dredging activities in Haeju Bay. How do we know that?

Broadly speaking, two types of vessels are most prevalent in these images—dredgers and barges. The tan-colored plumes in the water behind the dredgers indicate that they are pulling up sand from the seafloor. The sand plumes seen here are distinctly different to wakes left in water behind moving vessels.

In the Planet images, it appears that cargo barges are pulling up next to these dredgers to load the excavated sand. Other barges are either already fully loaded with sand or arriving in the area empty. Satellite imagery shows some barges with tan-colored cargo in their holds—suggesting a full load of sand—and others with dark shadows—suggesting empty holds. Consistent with information transmitted through AIS, the majority of the vessels in the images of Haeju are cargo ships.

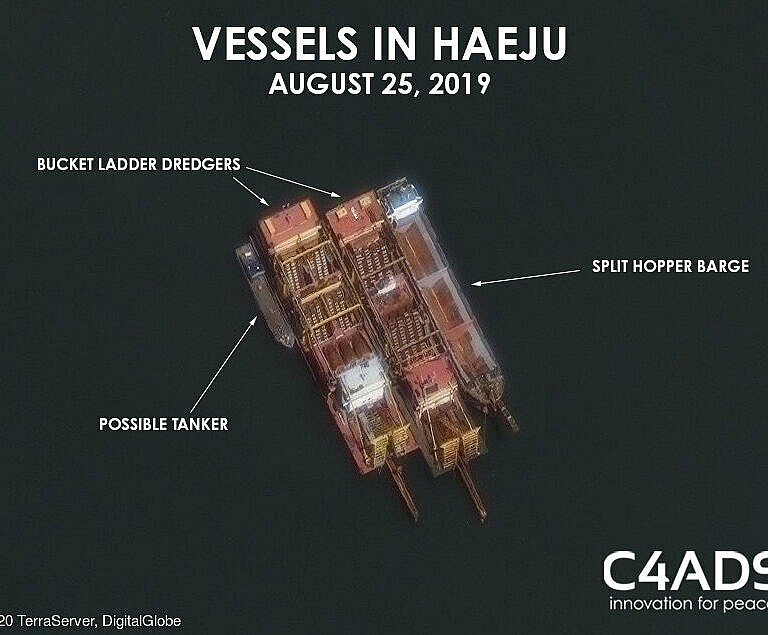

Although no AIS profiles transmitted from Haeju Bay on August 25, 2019, C4ADS obtained a high-resolution satellite image from Terraserver of four vessels in Haeju Bay that day. The image shows a split-hopper barge, two bucket ladder dredgers, and a possible tanker positioned side-by-side, offering further context on the organization of the Haeju sand dredging operations and identities of those involved.

HOW DID THE VESSELS GET THERE?

The voyage patterns of the vessels involved in the Haeju dredging activity exhibited several notable features. While in North Korea waters, the Haeju vessels sailed in a predictable pattern. From the Yellow Sea, they entered the strait between North Korea’s Ryongyon Peninsula and South Korea’s Baengnyeong Island. The vessels hugged the North Korea side of the Northern Limit Line, the disputed maritime boundary between the two Koreas, as they wound their way to Haeju Bay. The vessels then exited Haeju Bay using the same route.

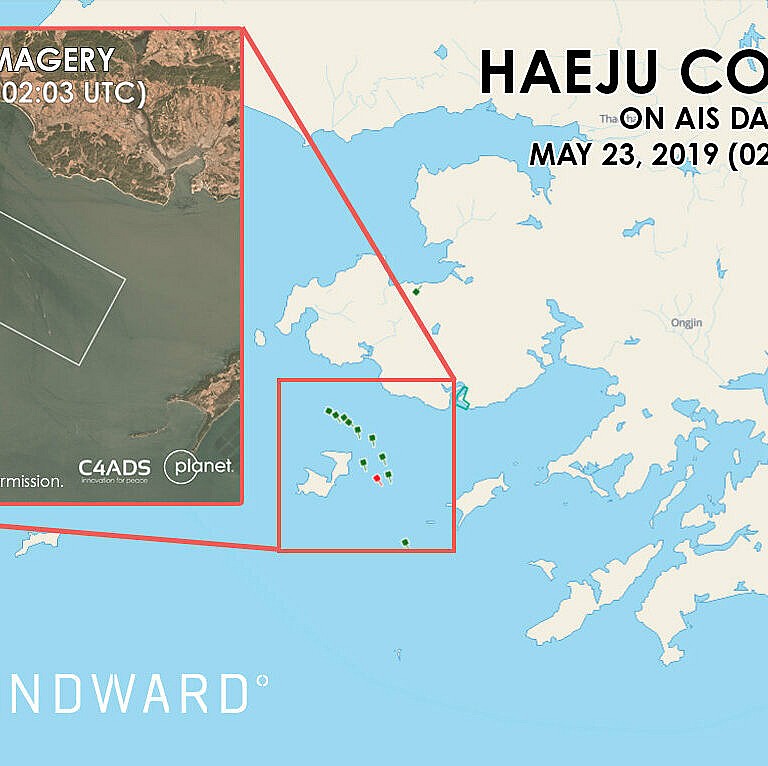

Satellite imagery and AIS data also show some Haeju vessels traveling in a convoy-like fashion, suggesting probable coordination between vessels at sea. For example, on the morning of May 23, 2019, Planet Labs photographed 14 vessels in North Korean waters en route to Haeju Bay. The vessels sailed in close formation, with one ship less than 500 meters behind the other. We matched 12 of these 14 vessels to their likely AIS signatures and tracked them as they entered the strait near the Ryongon Peninsula and sailed in sync towards Haeju Bay. Using the method above, we identified multiple instances of Haeju vessels traveling in convoys between March and August 2019.

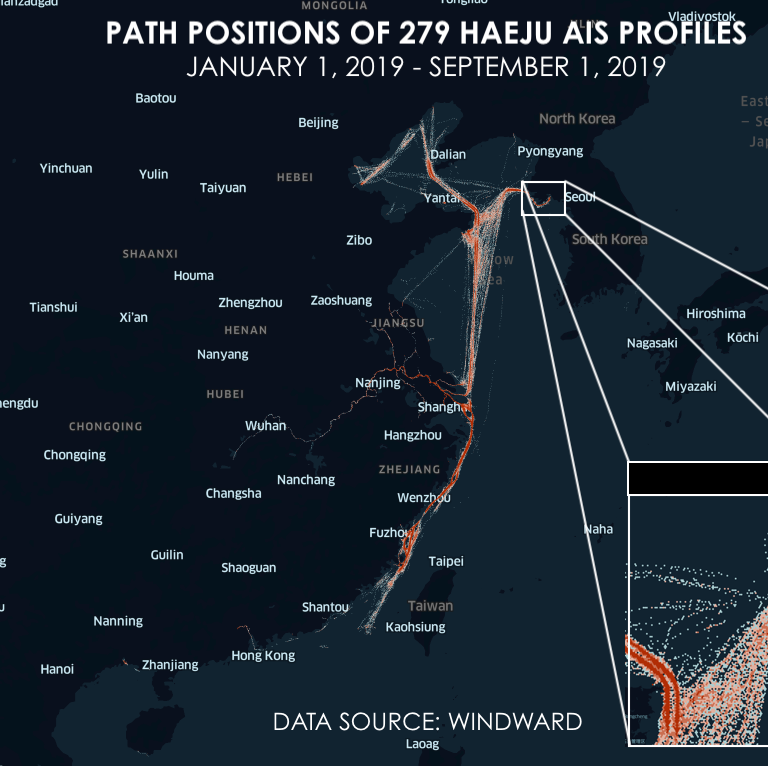

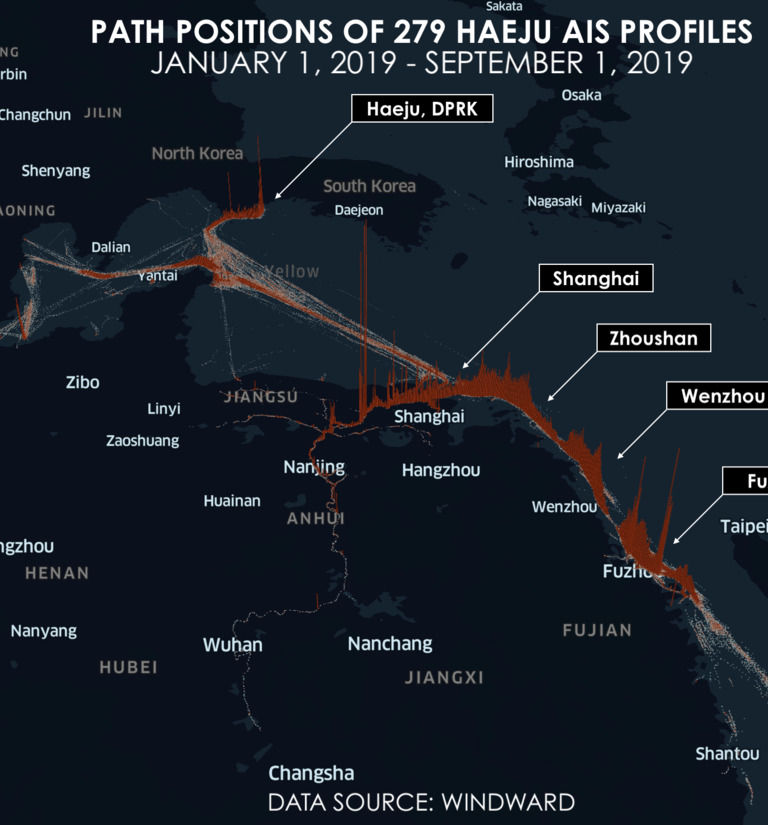

But where are these vessels coming from and where are they going? We visualized the path positions of the 279 AIS profiles that likely participated in the Haeju sand dredging operations from January 1, 2019 to September 1, 2019 below. China appears to be the primary origin and destination country for the Haeju vessels. From Liaoning to Guangzhou, the Haeju vessels sailed up and down the Chinese coast and operated nearly exclusively in Chinese territorial waters. The Haeju vessels also frequented domestic waterways within China such as the Yangtze River and its tributaries near Shanghai. Since none of the Haeju vessels reported an IMO number, it is possible that they are Chinese domestic vessels—therefore not required to apply for an IMO number— that were re-tasked to transport sand from the dredging operations in Haeju back to China.

Scale, Sophistication, and Implications of the Haeju Activity #

Through the above observations, we identified 279 AIS profiles which we assess with a high degree of confidence were involved in the sand dredging operations in Haeju Bay. A closer look at these AIS profiles suggested a high level of coordination among these vessels, and sophisticated tactics used to complicate the process of attributing the vessels to on-shore entities.

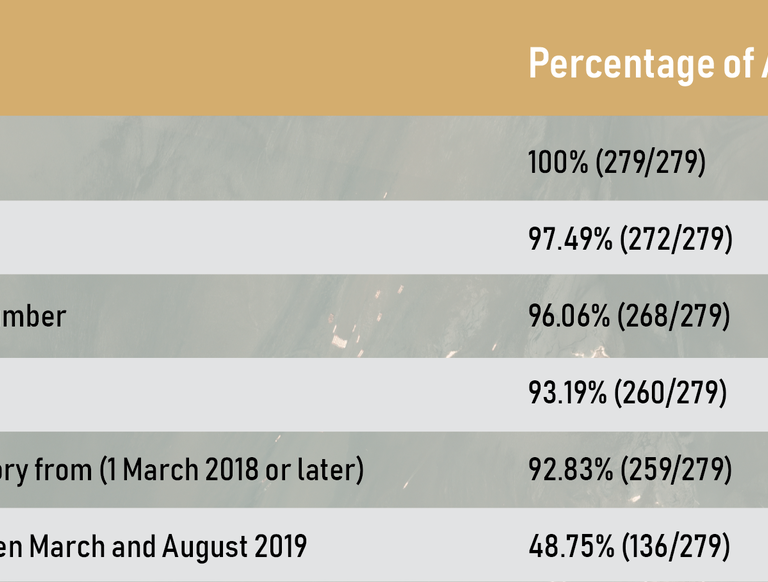

Despite the size of the fleet, the Haeju vessels are a relatively homogenous group. The 279 AIS profiles shared several common characteristics, which are detailed in the table below.

First, none of the 279 AIS profiles transmitted an International Maritime Organization (IMO) number—a permanent identification number assigned to every ship with few exceptions. Participation in the IMO number system requires submission of the vessel’s basic ownership and management information to an IMO-designated entity. Without an IMO number, the identities of the individuals and entities involved are obscured. The lack of transparency limits the ability of investigators to map the network back onto shore, where they are more vulnerable to law enforcement.

Second, the AIS profiles transmitted identifiers associated with Chinese registration, ownership, or management. We assessed that over 97 percent of the Haeju vessels reported a romanized Chinese name and over 96 percent transmitted a maritime mobile service identity (MMSI) number corresponding to a China flag registration. While it is not unusual for ships to change names and MMSI numbers, it is significant that the overwhelming majority of the Haeju vessels broadcast common identifiers.

Third, the age of the AIS profiles and timing of their creation may point to coordination and further attempts to obfuscate the identity of the vessels and their owners and managers. Over 92 percent of the AIS profiles were created after March 2018—just one year before the start of dredging activities in Haeju Bay. Furthermore, nearly half appeared for the first time between March and August 2019 when dredging activities were ongoing in Haeju Bay.

Conclusion #

The dredging and shipping of sand from Haeju Bay to China constitutes a violation of UNSC Resolution 2397 (2017). In other words, the sale of sand or sand-dredging rights is a typology of North Korean financing practice that the international community should be monitoring to enforce global compliance of sanctions on the DPRK. The Haeju case also demonstrates the importance of looking beyond established vectors of North Korean illicit financing and proliferation activities to date, such as coal, oil, or arms, and provides analysts with another angle through which to explore the DPRK’s participation in the illicit economy.

Moreover, the sand shipment activity in Haeju Bay is unprecedented in its scale and coordination, and speaks to the sophistication of DPRK capabilities to leverage entities and networks outside of its borders. The international community has never previously witnessed the DPRK engage in activities involving over 200 vessels over a sustained period of time and in coordinated fashion—the sheer number of transmissions within North Korean waters showcases the boldness and impunity with which sanctions evasion networks operate, even under close scrutiny.

Despite the audacity of the Haeju fleet, the international community is hard-pressed to find effective means to disrupt such illicit activity. The tactics deployed to obfuscate vessel identities on AIS transmission significantly complicate the task of identifying the vessels involved in sanctions violations, and connecting them to entities on shore. What we have seen in Haeju therefore prompts broader questions of how these capabilities and connections may be further leveraged for other forms of illicit revenue generation and proliferation activities by the DPRK.

In our follow up to this blog post, we hope to provide more insight into the strategic importance of North Korea’s sand trade. Stay tuned for more to come.

The authors would like to thank C4ADS research consultants Andrew Boling and LukeSnyder; Evan Accardi, C4ADS Analyst; Anna Wheeler, C4ADS Design Lead; and the many other individuals for their invaluable contributions to this project. The authors would also like to thank Ines Nastali and Christopher Owen of IHS Markit, and Kiran Pereira, Founder and Chief Storyteller at SandStories for sharing their expert insights.