Who Can Combat Forced Labor at Sea?

Forced labor at sea is rarely visible, but its witting and unwitting facilitators span the globe – and even our dinner tables. When a fishing vessel goes out to sea, it almost seems like it has disappeared from the world the rest of us inhabit. For months, the vessel and its crew fish in international waters, with little to no contact with those on land. This isolation creates a higher risk of forced labor, in which fishermen are forced to work in harsh conditions, often without pay or the fulfillment of their basic needs. To take a data-driven approach to some of these challenges, C4ADS has built a database of documented cases of forced labor in the fishing industry, enabling us to derive insights about the mechanisms and facilitators of forced labor in fishing.

Who Can Combat Forced Labor at Sea? #

When a fishing vessel goes out to sea, it almost seems like it has disappeared from the world the rest of us inhabit. For months, the vessel and its crew fish in international waters, with little to no contact with those on land. This isolation creates a higher risk of forced labor, in which fishermen are forced to work in harsh conditions, often without pay or the fulfillment of their basic needs. As with other forms of forced labor and human trafficking, the international and transnational nature of the crimes create challenges in identifying when crimes occur, how they occur, why they occur, and who can do something about it.

To take a data-driven approach to some of these challenges, C4ADS is building a database of documented cases of forced labor in the fishing industry. These cases are derived from information in the open source, partner organizations, and interviews with fishermen. The database aims to reconstruct the full scope of a given case from start to finish, from the recruiting companies to the final purchaser of catch. This means, to the extent possible, noting information about everything from the time period of the case to the ports that the vessel stopped at to the indicators of forced labor that were present in the case, alongside other relevant data points. By developing this database, we will be able to derive insights about the mechanisms of forced labor in fishing to drive more effective enforcement by states and other invested parties.

The first question we wanted to answer with this data is simple: what roles do different states play in these cases? Distant water fishing in international waters can occur outside the oversight of government, but it is still reliant on people, goods, services, and legal infrastructure in multiple countries. This gives these states, whether they are the home state of the fishermen or the end consumer of the fish that were caught, the ability to prevent these actors from committing human rights abuses. As our data shows, much of the world is more closely tied to this issue than may at first be imagined.

Below, we use this data to categorize how different jurisdictions play different roles in the forced labor cases we have encountered. Though our dataset is not a comprehensive sample of forced labor in fishing, likely overrepresenting and underrepresenting different states in different roles, it is still useful to identify how states are tied to forced labor, and therefore what enforcement opportunities are available to them. Using the data, we identified five significant ways in which states appear in these cases: as the source of the fishermen, as a transit point in the fishermen’s journey to or from the vessel, as the flag state of the vessel, as a port state that the vessel stops at, and as a market of the fish that are caught. Each of these roles provides states with different mandates and capabilities for addressing forced labor. Let’s take a look at each role in turn.

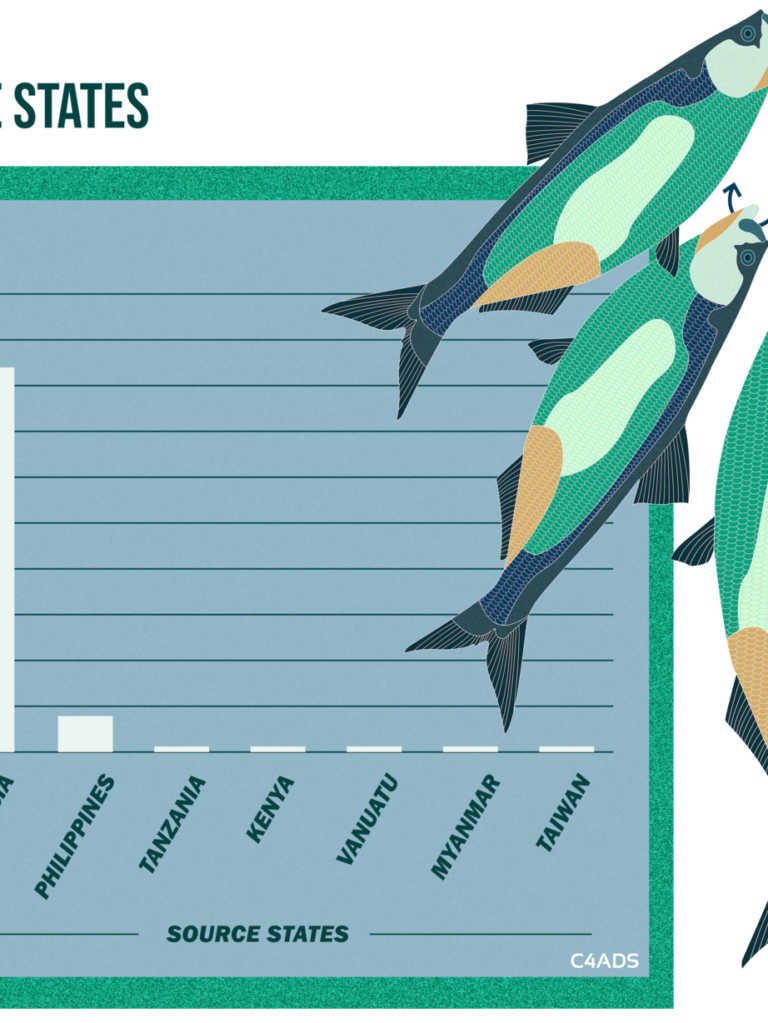

The Source States #

Many distant water fishing vessels are not crewed by fishermen from the country of the vessel owner, but instead by migrant fishermen from other countries. Much reporting has been done on the prevalence of Indonesian and Filipino fishermen on these vessels, and our data supports this as well. The vast majority of the victims identified in our cases were from Indonesia, followed by those from the Philippines. In almost all of these cases, we identified the manning agency, based in and regulated by the source state, that recruited the fishermen.

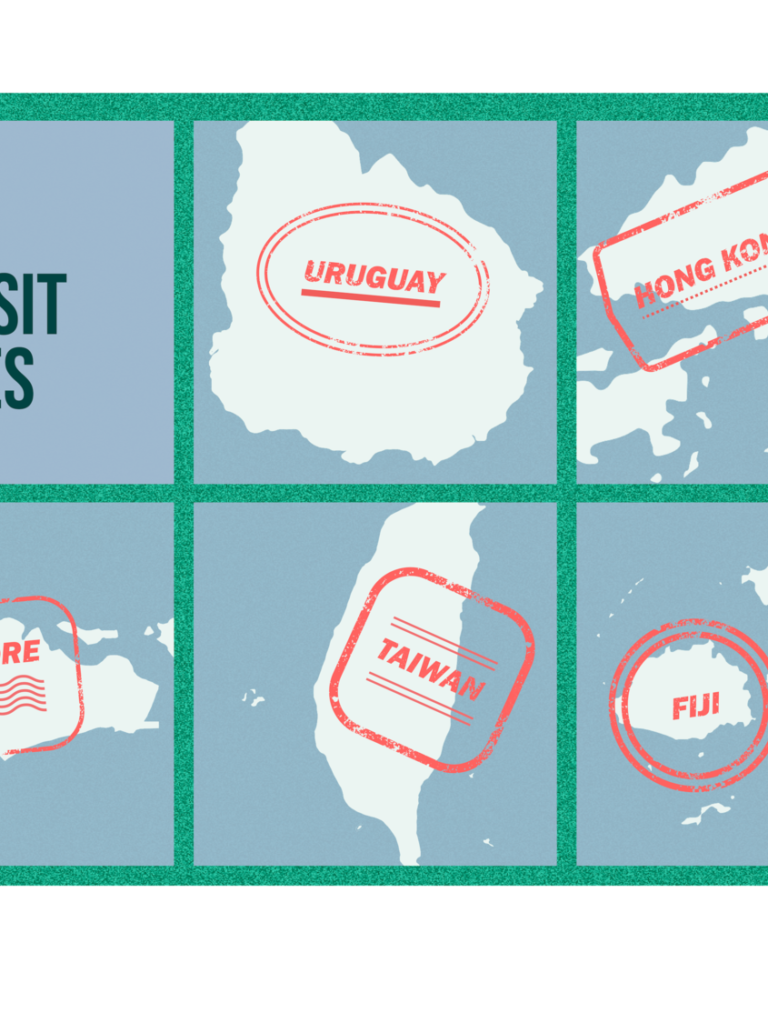

The Transit States #

We found that in many of our cases, fishermen travelled through intermediate countries before boarding the vessel and on their journey home from the vessel. While data on this leg of the journey was scarcer, particularly in cases found in the open source, the data that we do have provides a window into an often-overlooked stage of a fisherman’s experience of forced labor. The most common transit point in our case data was Singapore, followed by Hong Kong and Taiwan. Singapore and Hong Kong are both major economic and transit hubs in East and Southeast Asia, which may be the reason for their prominence on this list. Taiwan, on the other hand, is one of the most common flag states of the vessels in our database. These points of transit provide opportunities for the identification and disruption of forced labor prior to the fishermen boarding the vessel.

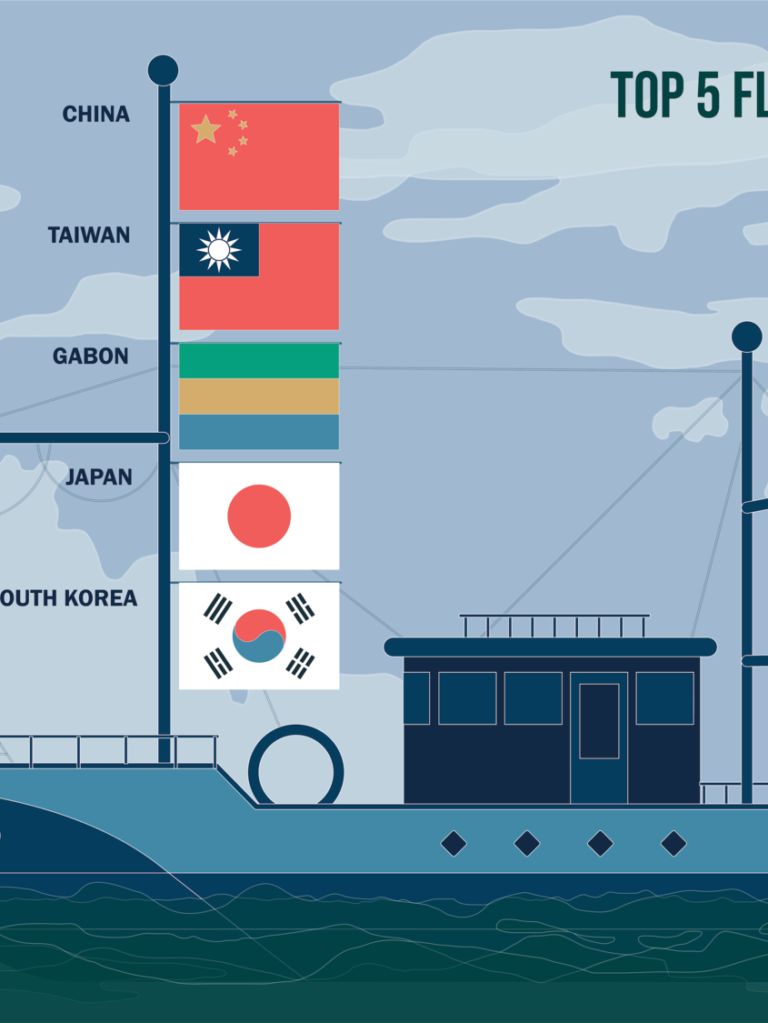

The Flag States #

States exercise authority over vessels that are registered to them and are flying their flag, even when the vessel is in international waters or within the waters of a foreign country. This means that the flag state of a vessel has jurisdiction when crimes, such as forced labor, are committed on board the vessel. In our dataset, China and Taiwan were the most frequent flag state of the vessel. China and Taiwan have the two largest distant water fishing fleets, but they are overrepresented in our case data compared to the next three biggest fleets: Japan, Korea, and Spain.

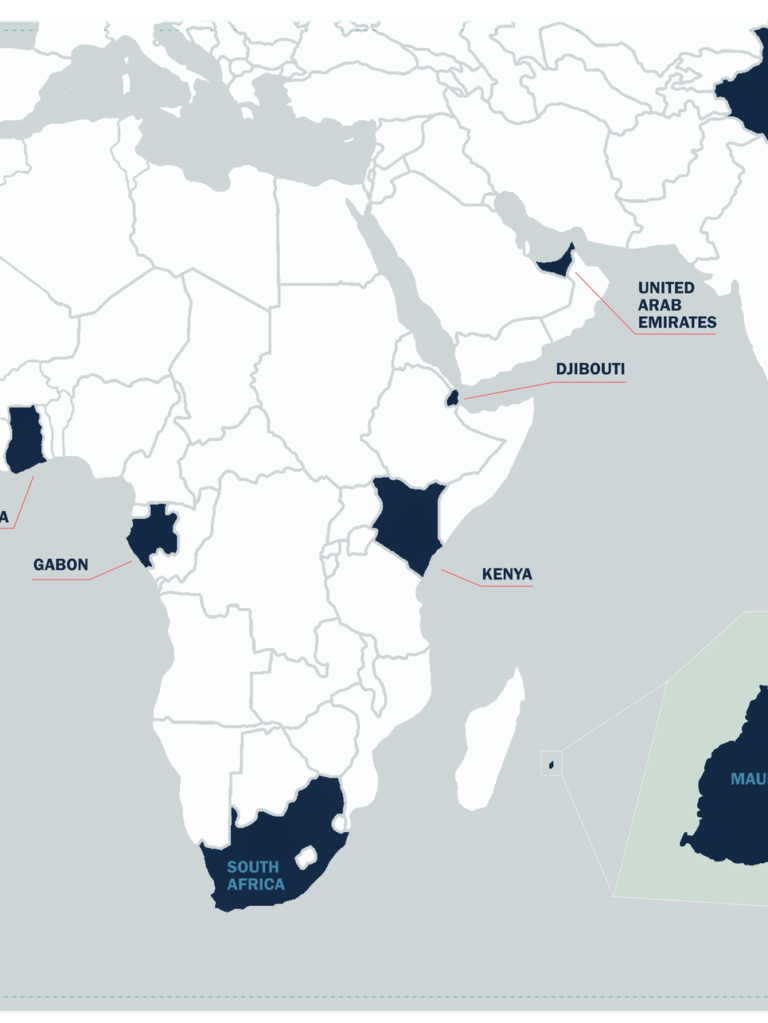

The Port States #

At some point, fishing vessels need to stop at port to restock, refuel, and offload fish, among other activities. During this time, the port state also has jurisdiction and can take measures against illicit activity such as forced labor or illegal fishing. We used information provided by the case sources as well as Windward Intelligence, a maritime domain awareness platform, to identify which port states were most frequently used by the vessels during incidents of forced labor. We found that the three most common port states were China, Taiwan, and South Africa. In the cases of Taiwan and South Africa, port calls were almost entirely centered around a single port (Kaohsiung and Cape Town, respectively), while in the case of China, port calls were dispersed across 10 different ports.

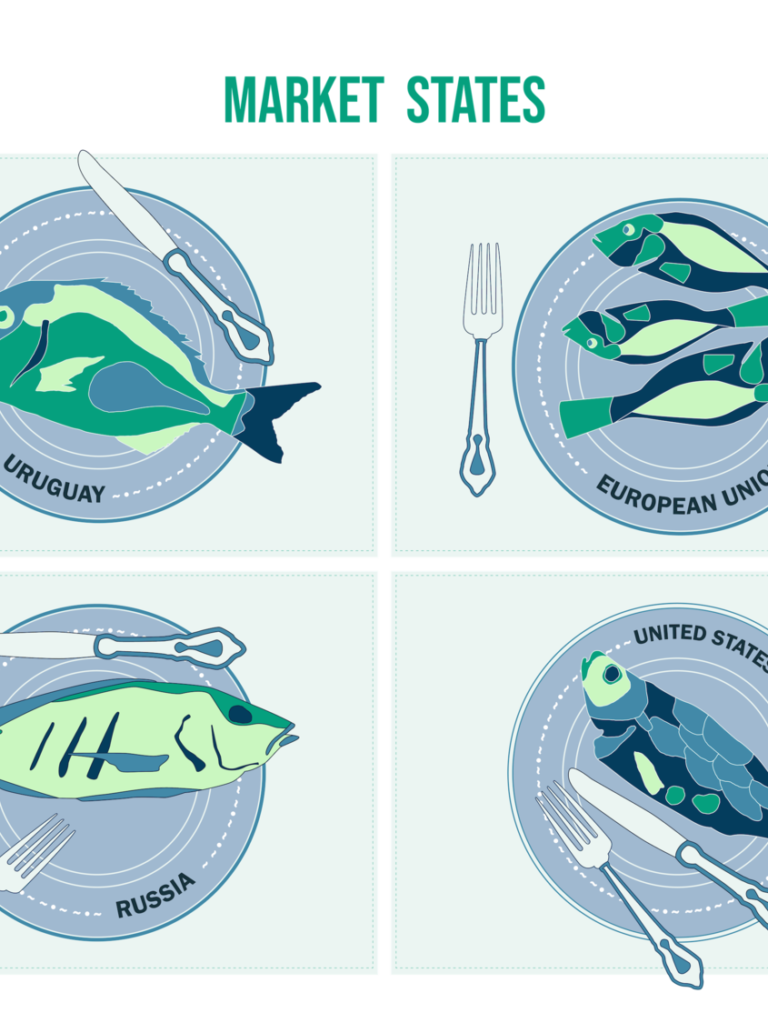

The Market States #

Forced labor in fishing is not confined to the vessels on which it occurs: the fish that is caught on these vessels travels around the world and lands on the plates of unsuspecting consumers. Proving a fish caught by a victim of forced labor is the same fish that shows up in the supermarket is difficult, but there are certain ways we can trace potential pathways. Some jurisdictions, like the European Union, only license certain vessels and companies to import fish, which we can compare against the vessels known to have employed forced labor. In other cases, we can identify trade from the companies that own these vessels to other jurisdictions. In our database, we used these methods to identify four jurisdictions that may be recipients of fish caught by forced labor: the European Union, the United States, Russia, and Uruguay.

By aggregating the states that play these five roles in our database, we identified 43 unique states, plus the European Union, that have a role to play in preventing forced labor in fishing. Within each role (and many states appeared across roles), states, as well as parties outside of government such as industry, financial institutions, and civil society, have unique mandates and tools to prevent, disrupt, and penalize the practice of forced labor in fishing.

Interactive: States Implicated in Forced Labor in Fishing Cases, by Role #

Forced labor at sea is rarely visible, but its witting and unwitting facilitators span the globe – and even our dinner tables. When a fishing vessel goes out to sea, it almost seems like it has disappeared from the world the rest of us inhabit. For months, the vessel and its crew fish in international waters, with little to no contact with those on land. This isolation creates a higher risk of forced labor, in which fishermen are forced to work in harsh conditions, often without pay or the fulfillment of their basic needs. To take a data-driven approach to some of these challenges, C4ADS has built a database of documented cases of forced labor in the fishing industry, enabling us to derive insights about the mechanisms and facilitators of forced labor in fishing.

Bringing a data-backed approach to forced labor can help analysts, law enforcement, and civil society better understand the causes, mechanisms, and avenues for disruption of the transnational trade in forced labor. This is particularly important on the world’s oceans, where the lack of a single state authority creates gaps which recruiters, unscrupulous vessel operators, and other members of illicit networks can exploit. As such, C4ADS and contributing partners will continue to build and analyze our forced labor in fishing case database for the purpose of better understanding this crime and how we can end it.