Indirect Fire

Despite extensive Western sanctions, Defense Industries System (MASAD) and its subsidiaries continue to use a network of subsidiaries to obtain ammunition components from India that enable indigenous arms production, facilitating ongoing armed conflict in Sudan.

Background #

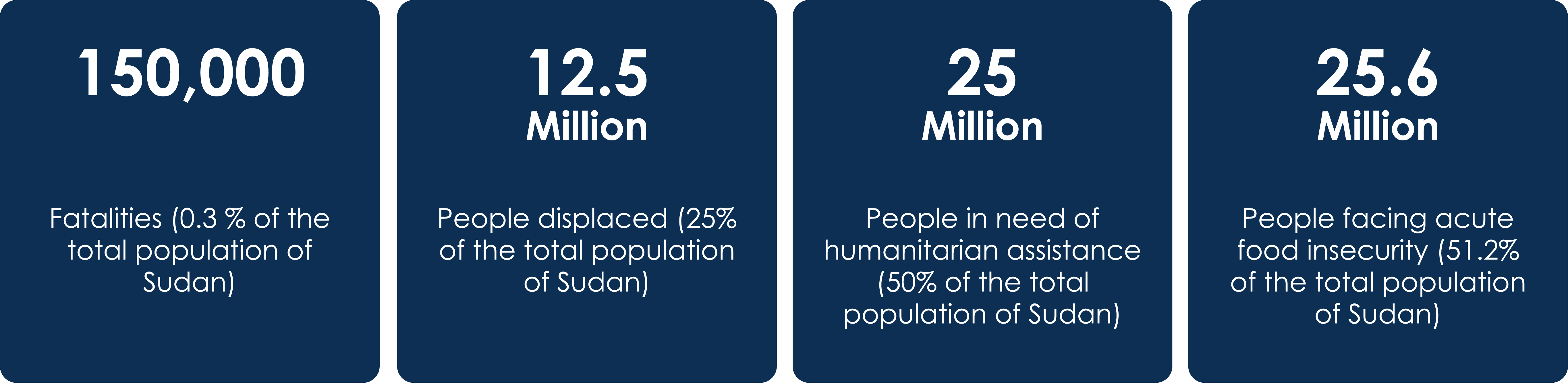

The 2023 ongoing armed conflict in Sudan has devastated the population. The U.S. State Department reported that the conflict “has resulted in the world’s largest humanitarian catastrophe” for Sudan’s 50 million residents.

As of the beginning of the third year of the crisis, it has resulted in: [1]

Expanded access to and availability of arms, ammunition, and military goods has continued to fuel the crisis. The Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) continue to equip themselves, and have mobilized domestic resources, including gold and oil, to procure weapons and potential precursor materials from other regions like Russia, India, Turkey, China, and the United Arab Emirates. The SAF and RSF’s exchange of Sudanese resources for military materials has created a self-sustaining war economy, which fuels both parties’ ability to prolong the war.

The Western-sanctioned Defense Industries System (MASAD) is Sudan’s largest defense enterprise, generating an estimated US$2 billion from a network of subsidiaries in the defense sector. MASAD serves as a weapons procurement arm for the SAF and is a key driver of the Sudanese war economy. Despite targeted sanctions from the European Union, the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom, Sudanese and Indian trade data show that MASAD and its subsidiaries continue to import goods that could be used to further manufacture and maintain weapons or military material.[2] With the SAF’s rising demand for weapons components and raw materials, MASAD is becoming an increasingly important pressure point in the SAF’s corporate network.

Using commercial trade data and public reporting, C4ADS took a deeper dive into MASAD, revealing the network involved in supplying materials with the potential for ammunition production in Sudan.

MASAD and Sudan’s Defense Industry, the Gears and Cogs of SAF’s Supplies #

MASAD, formerly known as the Military Industrial Corporation (MIC),[3] is controlled by the SAF. The primary role of MASAD is to supply and maintain the wide arsenal of arms, ammunition, military vehicles, and military material used by the SAF.

MASAD can be grouped into five complexes, each with their own function: [4]

MASAD’s relationships with state-controlled enterprises are obfuscated by a complex network of subsidiaries and affiliated entities. Some ownership connections to MASAD are obfuscated by partner corporations like the U.S.-sanctioned Sudan Master Technology Engineering Company Ltd. (SMT).Khartoum-basedSMT is a shareholder of multiple MASAD-affiliated companies involved in producing weapons, ammunition, and vehicles for the SAF. Both times the U.S. sanctioned SMT—May 29, 2007 and June 1, 2023—the U.S. Department of the Treasury linked the company to the alias Giad Industrial Group.[5] [6] Through these relationships, MASAD appears to exert direct or indirect control over a larger conglomerate of companies under the Giad Industrial Group, which claims it is one of the “largest pillars of the [Sudanese] national economy.” In this case, the MASAD-affiliated company of interest is Giad Elsewedy[7] Cables, which is a Sudanese branch of the multinational Egyptian company Elsewedy Electric SAE. According to Elsewedy Electric SAE promotional materials, Giad Elsewedy Cables was established in 2002 in a joint venture with the Giad group in Sudan.

The above graphic illustrates the complex network of entities connecting MASAD and Giad Elsewedy Cables.

Screengrab of Giad Industrial Group’s website on March 5, 2025 listing Giad Elsewedy Cables as part of the Giad “Group companies.”

RMIL and Indian Exports of Ammo Components to Sudan #

Trade data indicates that Giad Elsewedy Cables may be acting as an intermediary between MASAD and an Indian metals producer, Rashtriya Metal Industries Ltd (RMIL). According to its website and promotional materials, RMIL is a Mumbai, India-based company that produces cold-rolled strips in a wide range of copper and copper alloys. Its products include brass cups, a primary component of cartridge cases. RMIL advertises on its website that it has “global reach” that extends to Sudan. In February 2022, shortly after the October 2021 military takeover of the civilian-led transitional government in Sudan, MASAD reportedly signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with RMIL and several other Indian defense-related entities.

Commercially-available data suggests that MASAD and SMT produced ammunition for the SAF using components sourced from RMIL.[8] Sudanese trade records show that on August 22, 2023, Giad Elsewedy Cables imported 112 packages of brass cups, weighing a total of approximately 84,574 kg (186,452 lb) from RMIL.[9] Notably, trade data indicates that the shipments took place after the start of the conflict on April 15, 2023 and after subsequent U.S. sanctions of both MASAD and SMT on June 1, 2023.[10]

The brass cup is “drawn out” or processed through several stages until it becomes ready to be utilized in a cartridge.

Indian trade records indicate that between October 1 and 3, 2023, RMIL exported an additional 62,000 kg (136,686.6 lb) of brass cups to Giad Elsewedy Cables.[11] Sudanese trade records show that on October 19, 2023, Giad Elsewedy Cables imported 65,558 kg (144,530.6 lb) of wooden pallets.[12] While there is insufficient data available to definitively determine whether these are the same cargoes, there are notable correlations in timing, consignee, consignor, and weight.[13] RMIL does not list wooden pallets as a product available on its product page.

RMIL has made multiple exports of brass cups to Sudan between April and October 2023.[14] The amount of brass cups contained in RMIL’s July and August 2023 exports could be used to produce over 10 million cartridges.

All of RMIL’s brass-cup exports to Sudan are listed in available Indian trade records as being 7.62mm.[15] Human Rights Watch documentation from 1997 reports that 7.62mm ammunition was used in Sudan for seven types of high-power weapons, including AK-47/Type 56 assault rifles and PKM/type 80 machine guns.

Ammunition sizes and associated gun types identified in Sudan that are compatible with the brass-cups exported to Sudan by RMIL.

These weapons are common across Sudan: reporting from 2024 indicates that AK-pattern rifles remain popular, while reporting from August 2023 indicates there has been an influx of AK-47 rifles on the black market.

Ammunition-Caliber Brass Cups Exported to Sudan #

Available Indian trade data shows that RMIL has exported brass cups in common ammunition calibers (including 9mm, 5.56mm, 7.62mm, and 12.7mm) to foreign defense manufacturers, including to entities in the MENA region.[16] Indian and Russian trade data indicates that in 2018 and 2020 RMIL sent brass goods for shell production to the Russian arms manufacturer Joint Stock Company Tula Cartridge Works (TulAmmo),[17] which was sanctioned by the U.S. Treasury Department on July 20, 2023.[18] Sudan War Monitor has identified videos of SAF soldiers alongside boxes of TulAmmo-branded 7.62×39 ammunition in October 2024.

As such, the exports of 7.62mm brass cups from RMIL to MASAD through Giad Elsewedy Cables in 2023 suggest the possibility that the SAF’s supply includes domestically-produced ammunition. This may represent a larger trend in SAF procurement practices that ultimately decrease their reliance on external actors for small arms ammunition, in this instance through indigenizing production of ammunition previously sourced from foreign markets.

While it is possible that RMIL’s exports of brass cups to Giad Elsewedy Cables could be used for other industrial purposes, it seems unlikely for several reasons. First, RMIL is providing Giad Elsewedy Cables—a defense industry partner beneficially owned by SAF-affiliated state-owned enterprises (SMT and MASAD)—with brass cups, a product that RMIL leadership and advertisements have stated are for small arms ammunition. Second, given the dense network of connections between RMIL and defense corporations, as well as RMIL’s reported historic exports of brass cups to foreign defense-related entities like MASAD, RMIL’s shipments of precursor materials to Giad Elsewedy Cables may serve as a means of acquiring materials for domestic ammunition production in Sudan. Finally, according to Elsewedy Electric’s 2023 sustainability report, “GIAD Elsewedy manufacturing facility in Sudanwas not operational in 2023 due to the ongoing conflict,” further casting doubt on the brass cups’ potential use in Giad Elsewedy Cable’s non-defense manufacturing processes. It is likely that these shipments supplied sanctioned entities with materials that can produce ammunition for the SAF, which uses ammunition of the corresponding caliber.

Context note sources:[19] [20] [21]

Implications of the Indigenization of Ammunition Production #

Precursor materials and components used in the production of arms and ammunition contribute as much to exacerbating the conflict and humanitarian crisis in Sudan as the arms and ammunition themselves, and the procurement of these materials deserves just as much international attention as the flow of arms. The importation of brass cups from entities like RMIL for domestic ammunition production suggests that MASAD and SMT may be having to expand or restart ammunition production that was previously sourced from external actors. The indigenization of ammunition production may make targeted enforcement actions more difficult, and could undermine the United Nations arms embargo on Sudan. Importing separate components of ammunition such as the brass cups imported from RMIL—rather than outright importing completed arms or ammunition from known actors like TulAmmo—obfuscates traditional arms procurement pathways, making enforcement more complex. The Giad Elsewedy Cables case exemplifies how the SAF obfuscates its activity by operating through companies that are not immediately identifiable as SAF-affiliated entities. As such, improving due diligence, monitoring, and regulation of the export of raw materials and components for military equipment to conflict zones is a necessary step in closing vulnerabilities that allow actors like the SAF to side-step sanctions and arms embargoes.

[1] https://www.nytimes.com/2025/01/07/world/africa/sudan-genocide-numbers.html; https://www.unrefugees.org/news/sudan-crisis-explained/#:~:text=More%20than%20one%20year%20since,who%20fled%20to%20neighboring%20countries.;

[2] Sudan and India Trade Data

[3] When searching for MASAD in C4ADS’ State-Controlled Enterprise Explorer, please note that both its current name (Defense Industries System) and historic name (Military Industrial Corporation) should be selected.

[4] https://web.archive.org/web/20180409195733/http:/www.alshagara.sd/index.php/pages/index; https://sudantribune.com/article43647/; https://www.smallarmssurvey.org/sites/default/files/resources/HSBA-WP-18-Sudan-Post-CPA-Arms-Flows-arabic.pdf; https://presidency.gov.sd/news/amanamatakhtet; https://safataviationgroup.com/safat-aircraft-manufacturing-and-development-complex/.

[5] Government of the United States, “Sudan / Darfur Designations,” Department of the Treasury, May 29, 20007, https://ofac.treasury.gov/recent-actions/20070529.

[6] Government of the United States, “Counter Terrorism Designations; Sudan Designations; Russia-related Designation Removal; Issuance of Sudan General Licenses,” Department of the Treasury, June 01, 2023, https://ofac.treasury.gov/recent-actions/20230601.

[7] When searching Giad Elsewedy Cables or other entities whose names contain “Elsewedy” in C4ADS’ State Controlled Enterprise Explorer, please note that these entities are listed under the term “Swedish” instead of “Elsewedy” due to a direct translation from Arabic.

[8] Sudan and India Trade Data

[9] Sudan Trade Data

[10] Sudan Trade Data

[11] India Trade Data

[12] Sudan Trade Data

[13] Neither trade records indicated whether this was gross or net weight.

[14] India Trade Data

[15] India Trade Data

[16] India Trade Data

[17] India and Russia Trade Data

[18]Available Russian trade records indicate that the shipments in question contained “brass caps.” One of the shipments explicitly indicates that the caps in question are for use in shell production. Source: Russia Trade Data

[19] https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/sudan-military-factions-battle-over-weapons-fuel-depots-2023-06-07/

[20] https://www.voanews.com/a/massive-fire-as-sudanese-factions-battle-for-control-of-arms-factory/7127618.html

[21] Commercially-available trade data