Open Secrets

In this update to our 2022 Trade Secrets investigation, we share evidence of increased wartime trade in sensitive defense technologies between state-owned Chinese conglomerates and sanctioned Russian defense companies — as well as the presence of one key entity, Poly Technologies, in Western supply chains and capital markets.

Introduction #

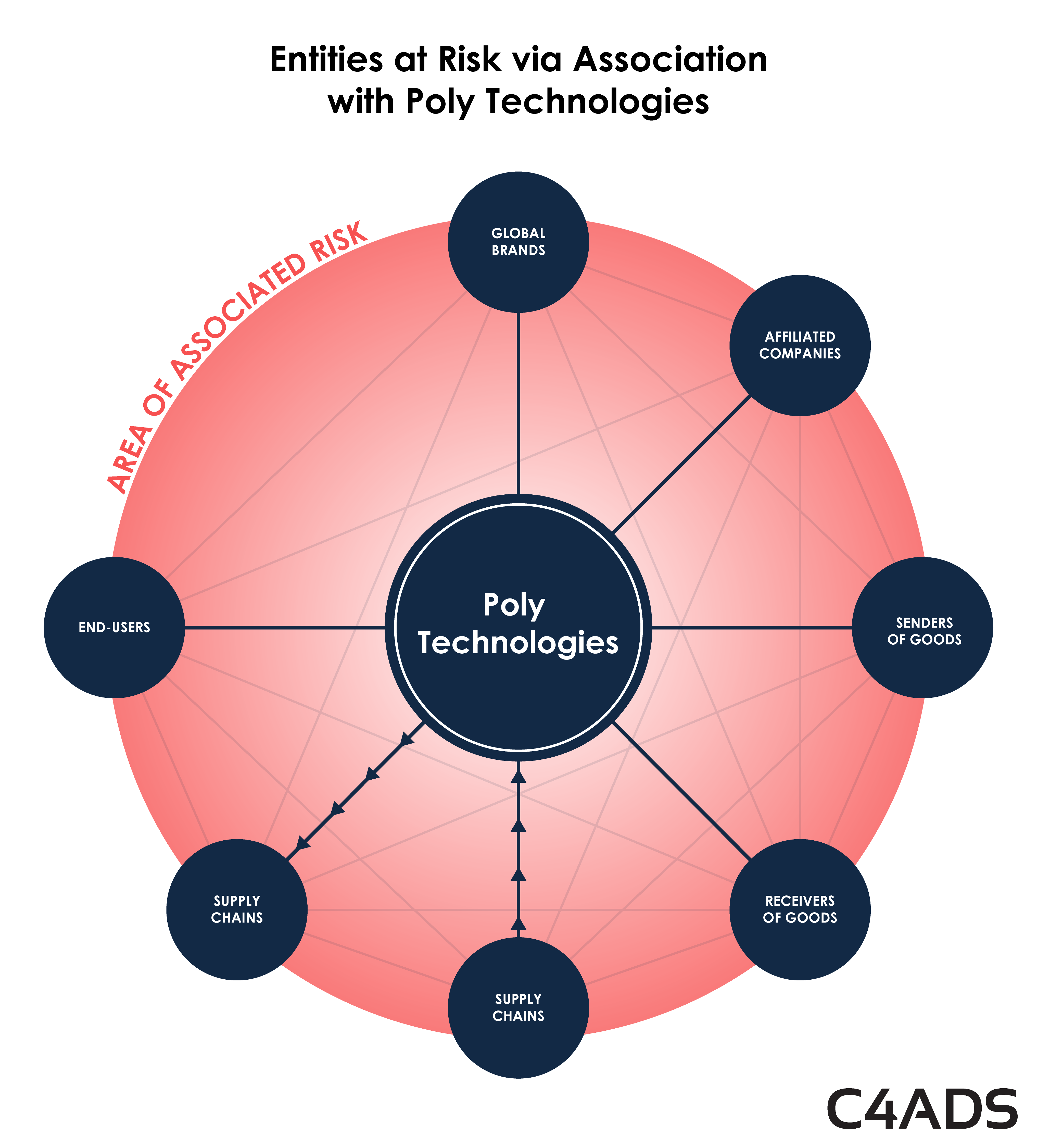

Recent updates to Russian and international trade data show an increase in trade in sensitive technologies from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) state-owned defense company Poly Technologies Inc (保利科技有限公司) to sanctioned Russian defense companies since Russia’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine. These records shed light on an opaque network of Chinese and Russian companies that trade in military-applicable[1] technologies at a time when both Beijing and Moscow are bolstering their military cooperation, laying the groundwork for a renewed period of global instability. These networks of companies financially and materially supporting Russia-PRC wartime defense-applicable trade are not isolated. Publicly available information shows entities of Poly Group – of which Poly Technologies is a 100% wholly-owned subsidiary – in Western supply chains and capital markets, directly implicating unwitting consumers and nation-states in supporting Russia’s wartime acquisition of financing and military-applicable goods.

- According to aggregated global trade data, from June 2 to November 16, 2022, Poly Technologies exported 13 shipments labeled as spare or used parts for the Mi-171, Mi-Sh, and other unspecified Mi-system helicopters to the sanctioned Russian defense and aviation company Ulan-Ude, and one such shipment to Russia’s sanctioned United Engine Corporation.

- This same trade data indicates that three of these post-invasion shipments from Poly Technologies were labeled as spare parts for the Russian Mi-8AMTSh (Ми-8АМТШ; МИ-171Ш), a military assault helicopter that Russian sources report has been used in the war against Ukraine.

- Ulan-Ude is a Russian state-owned defense company subject to new rounds of stricter international sanctions in December 2022 through March 2023 for the production of items “that have been used in Russia’s assault against Ukraine.”

- The apparent timeline of these shipments may indicate a growing Russian need for Mi-system helicopter parts. Trade records indicate that more than one-third of Poly Technologies’ total M-system helicopter shipments to Russia since 2014 took place in the nine months following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

- International entities that trade with or invest in Poly Group entities or Poly Technologies’ primary trade partners should rigorously vet their supply chains to avoid any risks associated with financially or materially supporting sanctioned Russian defense supply chains, even unwittingly. See “Secondary Sanctions Risks Explained” below for more detailed information.

Reliable aggregated global trade records indicate that the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC’s) state-owned defense company Poly Technologies, Inc. (保利科技有限公司) has neither stopped nor decreased its trade in sensitive technologies with Russian state defense companies since the start of Russia’s war against Ukraine and the imposition of broader Western sanctions against Russia. In fact, global trade records indicate an increase in Poly Technologies’ total exports to Russia after the start of the invasion—including in parts explicitly labeled for use in Russia’s Mi-system helicopters.

These reported trade flows between PRC and Russian state military conglomerates come at a time when Beijing has touted its “no limits” partnership with Russia, even promoting high-level meetings between PRC and Russian officials during Russia’s war. As widely reported in Western media at the start of Russia’s aggression in Ukraine, PRC General Secretary Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin convened on February 4, 2022—less than three weeks before Russia’s February 24 invasion—to announce a strategic “no limits” partnership between the two countries in all sectors of industry and trade. After the start of the war, the two leaders next met in September 2022 at the Shanghai Cooperation Organization summit, again confirming their unlimited “comprehensive partnership” after seven months of Russia’s ongoing attack. In the months following, Beijing continuously refused to denounce Russia’s aggression, even naming the United States as the “main instigator” of the war against Ukraine.

While international leaders have worked to understand the bounds of the two countries’ “no limits” partnership—with China continuously denying any military aid to Russia—perhaps the most telling is China’s response to new findings derived from publicly available trade data. In early February 2023, international news agencies, including the Wall Street Journal and DW News, published reports detailing military-use shipments sent from China to Russia after the start of the war. In response to these reports, initial Chinese state media denied these exports, calling the findings “totally false,” and even denounced the researchers as “alarmist” and “untrustworthy,”[2] in line with Beijing’s official stance that it has “not provided military assistance” to Russia. Beijing even co-opted these denials to further promote its stance that the United States was to blame for the war, with China’s state-run English-language media unit, the Global Times, reporting on February 22, 2023, that research into PRC-Russia military trade only exposes the “ill intentions of Western media,” while still refusing to take a stance against Russian aggression.[3]

After the publication of numerous late-February international media reports further detailing military-applicable PRC exports to Russia, Beijing shifted its stance. From mid-to-late February 2023, multiple prominent international media outlets, such as Qatar’s Al Jazeera, Japan’s Nikkei, Australia’s The Australian, the U.S.’s CNN, and the U.K.’s Daily Mirror, published articles detailing Poly Technologies’ and other PRC companies’ dual-use shipments to Russia after the war began. On February 24, 2023, the anniversary of the start of the war, the PRC’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs published an official call for a “comprehensive ceasefire” in Ukraine. International media outlets highlighted the change, reporting that “China calls for Russia-Ukraine ceasefire as claims to neutrality questioned.”

Amid this increased public scrutiny, Beijing has not only dropped its denials of supporting Russia’s war effort, but the state-owned Poly Group has also partially withdrawn its presence from Western nations. Canadian news agencies such as BIV and Breaker reported that, in late February 2023, Poly Group’s art gallery operator Poly Culture Art Center, “quietly closed its […] art gallery in downtown Vancouver” and that its holding company Poly Culture North America Investment Corp. Ltd. “quietly closed its North American office in Richmond,”[4] Canada. Both news agencies cited recent C4ADS trade data findings on Poly Technologies as possibly connected to the unannounced closure of the Poly Group companies in North America.[5]

While there is no indication that the nature or purpose of these goods has been obfuscated in recorded shipments from China to Russia, this may be due, in part, to the fact that large-scale analysis of global trade data has traditionally been limited and therefore overlooked as an area of enforcement risk for these trading companies. Global trade data aggregation for public reporting has been historically challenging due to the time and cost of collecting global databases, the large data storage capacity required, the need for foreign-language expertise, and the computational difficulty of aggregating variations on reported company names. For more information on global trade data research and computational techniques, refer to the July 2022 C4ADS report, Trade Secrets.

Trade Secrets identified 281 previously unreported military-applicable dual-use exports from PRC state-owned Poly Technologies and its subsidiaries to sanctioned Russian defense companies that currently support Russia’s war in Ukraine. Since the beginning of the war, C4ADS continued to track Poly Technologies’ global trade and identified 14 new exports of potential dual-use goods to sanctioned Russian wartime actors during the ongoing invasion of Ukraine.

This publication relies on aggregated global trade data to achieve three primary purposes: to expose and deter illicit defense networks present in global supply chains, to assist international enforcement agencies in detecting those networks in their markets, and to inform international trading companies of the risks of indirectly or unwittingly transferring goods through sanctioned Russian supply chains. We hope to empower similar international research organizations to use trade data for findings that promote peace and security. C4ADS encourages international trading companies to search for their trading partners in global trade data before doing business to understand upstream and downstream risks they may be unaware of in their supply chains.

Methodology #

The C4ADS Approach: 1.5 Billion Aggregated Global Trade Records

The analysis presented in this report stems from C4ADS’ continuous efforts to collect, clean, and quality check global trade records from reliable reporting jurisdictions and third-party trade data providers. To date, C4ADS has collected and harmonized approximately 1.5 billion reliable global import and export records detailing shipments to or from more than 200 jurisdictions using Palantir Foundry. At the time of writing, analysts have not identified any comparable at-scale free-text search databases of global trade records available for public reporting.

This analysis identifies exports from companies based in China, which stopped publicly releasing its trade records around 2018. To identify military-applicable exports from China without using Chinese trade records, C4ADS analysts instead use global records of imports from China to mirror PRC shipments abroad. In this analysis, C4ADS researchers use Russian import records to attempt to identify Poly Technologies’ exports to Russia and the Russian defense companies that have received Poly Technologies’ shipments.

Given the self-reported nature of each jurisdiction’s global trade, there is no way to confirm the comprehensiveness of a given set of trade records. However, statistical information for C4ADS’ dual-use Russian trade records closely matches those of the trade statistics reported by UN Comtrade.[6] Still, given the nature of such limitations, C4ADS does not aim to present a comprehensive view of PRC exports globally; instead, we offer this data as a baseline to identify and detect individual companies and shipments that can be corroborated with other sources of data.

Wartime Shipments #

Aggregated global trade records indicate that leading up to and during Russia’s invasion of Ukraine from mid-January 2022 to December 31, 2022 (the most recent available data), Poly Technologies’ total recorded exports, including potential dual-use technologies to sanctioned Russian defense companies, was more than 15 times higher than the previous year. These reported shipments may indicate an effort by the PRC and Russian state military apparatuses to acquire increased access to financial and technical capabilities with direct military applications. See below for a timeline visualization of the trade data indicating Poly Technologies’ total shipments to Russia since January 1, 2022.

Trade data indicating increase in Poly Technologies’ exports to Russia mid-January 2022, with an increase in Mi Helicopter Parts Exports beginning July 2022

The newly released trade records show that Poly Technologies exported all 21 of its postwar shipments to Russia to two sanctioned state-owned Russian defense companies: JSC Ulan-Ude Aviation Plant (Ulan-Ude; “ОАО Улан-Удэнский авиационный завод”) and JSC United Engine Corporation (UEC; “АО ОДК”). From June to November 2022, trade records show that Poly Technologies exported 20 parts shipments to Ulan-Ude and one shipment to UEC. Russian importers Ulan-Ude and UEC were both subject to new North American, Oceanian, and European sanctions before April 2022, specifically for their facilitation of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, including the manufacture of M-system military aircraft and accessories.[7] All recorded post-invasion shipments from Poly Technologies are listed here. We include dates, Russian recipient companies, and original Russian-language goods descriptions with no alterations.

According to the data, these post-invasion exports from Poly Technologies included three shipments to Ulan-Ude of electromagnetic control and engine regulation parts labeled for use in the Russian Mi-8AMTSh (Ми-8АМТШ; МИ-171Ш) combat, assault, and military transport helicopters. Prominent international and Russian media sources have cited Russia’s use of the Mi-8AMTSh in its ongoing invasion of Ukraine. In late April 2022, Izvestia (Известия) and other Russian pro-state media agencies detailed the Russian army’s use of the Mi-8AMTSh assault helicopter to “destroy” Ukrainian defenders in a “special operation” in Donbas. (See below.)

Russian Ministry of Defense footage of Mi-8AMTSh assault helicopters used by the Russian army in Ukraine.

The remaining 11 post-invasion M-system helicopter parts shipments from Poly Technologies to Russia appear to have included parts for radio receivers, engine starters, helicopter telecommunications devices, and helicopter hydraulic system components. One of these 11 shipments was labeled only for generic use in “Mi Helicopters,” while the remaining 10 were logged for Mi-8AMT (Ми-8АМТ; Ми-171Е) helicopters, which are primarily used for non-combat army personnel transport but easily modified for use in the aforementioned Mi-8AMTSh assault helicopter variant. An undated Russian military news website accessed in March 2023 reports that “a significant portion” of Ulan-Ude’s Mi-8AMT helicopters are being “upgraded to the Mi-8AMTSh variant.”

As detailed above, Poly Technologies’ post-invasion exports to Russia appear to have consisted primarily of component parts labeled for use in Russia’s M-system helicopters, sent to Ulan-Ude. Available trade records even report a total increase of Poly Technologies’ M-system component parts shipments to Russia after the beginning of the war, compared with all shipments from 2014 to March 2022.[8] These records show that more than one-third of Poly Technologies’ total M-system parts shipments to Russia from 2014 to the present took place after the start of the invasion (see below).

Available trade records also show increased total Poly Technologies exports to Ulan-Ude during the invasion (see below). According to the data, approximately one-third of Poly Technologies’ total exports to Ulan-Ude from 2014 to the time this report was published[9] took place after the 2022 invasion of Ukraine began.

Notably, from January 1, 2021 to January 2022, before the war began, Poly Technologies exported 27 total shipments labeled as “for warranty repair” to Russia, though none of these were Mi-system shipments, according to the data.[10] These exports reportedly included electronic modules as well as ambiguous shipment descriptions such as “property for the KA helicopter.”[11] Given the discrete nature of each shipment record, researchers cannot comprehensively confirm the intended nature or end-use of any given shipment. This raises the question of whether an undisclosed percentage of Poly Technologies’ parts exports to Russia were returned to the original Russian manufacturing companies for repairs or updates, in addition to direct exports to Russia.

There is also the possibility these shipments comprised used, spare, or remanufactured parts left from Poly Technologies’ earlier purchases of M-System helicopters from Russia without any additional manufacturing. This could indicate a Russian need for spare parts for the Mi-8AMTSh assault and other helicopters or could also point to a PRC interest in acquiring updated Russian military aviation technologies in the future—an excellent topic for further study.

While the complex nature of bilateral trade prevents analysts from determining the ultimate destination of these shipments, our takeaways remain the same. These shipments together depict an escalation in the financial and material relationship between a prominent PRC state defense company and Russian defense companies sanctioned for supporting the war in Ukraine, all after the war began. These findings underline two primary conclusions:

- The PRC has not halted military-applicable trade with Russia in response to the war in Ukraine, despite PRC claims to the contrary.

- Companies that send or receive goods through Poly Technologies or its affiliates may be at risk of exposure to sanctions and must carefully investigate end-users to avoid potential penalties. See the section “Secondary Sanctions Risks Explained” for information on the risks of trading, even unknowingly, in such sanctioned supply chains.

Secondary Sanctions Risks Explained #

In response to Russia’s initial aggression in Ukraine in February 2014, many international jurisdictions imposed heavy sanctions on Russia to prohibit the transfer of dual-use and sensitive technologies. These sanctions protocols have become increasingly strict since Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, with new heightened penalties and restrictions for trade in any goods with sanctioned Russian entities. Each jurisdiction maintains its own set of prohibitions for trade with Russia, and trading companies are responsible for following the laws of their jurisdictions and those in which they trade. However, many jurisdictions’ anti-Russian sanctions measures follow similar protocols prohibiting even the indirect transfer of goods to Russian defense supply chains.

This means that entities found to have transferred or received goods through Russian defense supply chains via any international trade participants may be at risk of sanctions penalties from their domestic authorities, regardless of whether the transfer was intentional. For example, the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) sanctions on Russia prohibit domestic companies from sending goods—knowingly or unknowingly—that are later diverted to any OFAC-sanctioned end-user. In a July 2020 OFAC settlement, Amazon.com paid US$134,523 to settle a potential civil liability case for mistakenly selling goods to users located in Crimea, Iran, and Syria, which OFAC found was due to automated sanctions screening processes that “failed to fully analyze all transaction and customer data.” Previous C4ADS reporting in Trade Secrets also details U.S. technology company Cobham Holdings Inc.’s 2018 civil liability investigation settlement of US$87,507 for indirectly transferring goods to Russia’s sanctioned defense company Almaz Antey through Canadian and Russia distribution companies.

These stipulations mean that all international trading companies must thoroughly vet their supply chains, goods producers, and end-users to avoid potential penalties associated with unwittingly supporting sanctioned defense networks. For a company like Poly Technologies, trading companies are encouraged to strongly investigate all legs of a shipment’s journey—import or export—that may transit any of Poly Technologies’ trading partners.

Presence in Western Markets #

Trade in Goods

According to the data, from 2018 to the present, Poly Technologies has traded with over 100 international counterparts that trade in Western goods or with Western-domiciled companies. While this trade took place at least four years after the initial rounds of international sanctions on Russian defense companies in response to Russia’s 2014 invasion of Ukraine, this trade does not in any way indicate the trade partners listed below are or have been in violation of any international sanctions. This analysis of Poly Technologies’ Western-touching trade highlights the depth of Chinese defense conglomerates’ footprints in Western supply chains and underscores the need for all trading companies to thoroughly investigate their end-users before engaging in international trade. This analysis aims to assist international trading partners in understanding the risks present in their supply chains. It does not in any way indicate these companies have transferred potential dual-use items to Russia through Poly Technologies.

Poly Technologies’ top-five trading partners since 2018 with Western trade are VMI Holland BV, the Ministry of Defence and the National Police Service of Uganda, The Officer Commanding (OC) Pakistan, Aircraft Rebuild Factory of Pakistan, and CO PNS Raza of Pakistan, according to the data. This depicts Poly Technologies’ trade with Western trade partners since 2018, showing the interconnectedness of our global supply chains and the possibility of unknowingly trading, directly or indirectly, with sanctioned end-users.

Capital Markets

In addition to their presence in global trade markets, publicly-traded Poly Group companies also appear in U.S. capital markets. The California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS)—widely considered the largest U.S. public pension and retirement system—holds shares in three Poly Group companies, according to its 2022 annual report. CalPERS’ most recent available Annual Investment Report, which details the retirement system’s investments for the fiscal year ending in June 2022, lists US$3.6 million directly invested in shares of three Poly Group subsidiaries.

CalPERS reported at the time of its most recent annual report that it holds the following:[12]

Conclusion #

This investigation only pulls on one thread of the PRC’s efforts to assist Russia in its war of aggression against Ukraine, inviting the question of whether the cooperation may be more extensive than Poly Technologies. Indeed, the PRC’s increasing willingness to test redlines around its state-owned companies’ trade with Russian defense firms adds to an already fragile geopolitical environment that risks growing instability and potential conflict. Within this context, an array of U.S. and international firms, many of which have legitimate business dealings with Beijing-based companies, will have to face the choice of either divesting their interests from the opaque web of Chinese-Russia trade ties or at least accepting the consequences of public scrutiny for supporting Moscow’s war in Ukraine, if not the prospect of secondary international sanctions. While sanctions have failed to deter the PRC from trading with the Russian defense industry thus far, the public fallout of doing business with companies trading with the Russian defense industry could very well hurt unwitting affiliated U.S. companies and shrink economic gains. It may take real financial hardship to slowly turn the tide of the PRC partnership with Russia. Even then, geopolitical calculations will likely drive the relationship now and in the years to come.

Poly Technologies’ Wartime Exports

The chart below lists all 21 of Poly Technologies’ post-February 24, 2022, exports to Russia as reported in Russian customs records, including the date, recipient of Poly Technologies’ export, and goods description. The goods description is included in its original Russian as provided verbatim from the original data with no alterations.

Notes

C4ADS would like to thank all those who provided guidance and support during this project. The authors would like to particularly thank the C4ADS analysts who supported one or more aspects of the creation of this report: Andrew Boling and Sara Thelen for shaping and editing the writing, and Anna Wheeler and Brody Morgan for improving the report layout and design.

[1] The term “military-applicable” refers to items or component parts that have the potential to be used by military forces and civilians. For example, an oil tank shipment has the potential to be used in simple civilian automobiles; however, given the nature of the trade flow of military-applicable goods from one sanctioned state-owned defense manufacturer to another, these shipments are labeled high-risk. More detailed information on each of the identified shipments in question is provided below.

[2] Lanlan and Wenting, “GT investigates.”

[3] Lanlan and Wenting, “GT investigates.”

[4] Mackin, “B.C. arm of powerful Chinese state-owned conglomerate closes office, gallery.”

[5] Mackin, “B.C. arm of powerful Chinese state-owned conglomerate closes office, gallery.”

[6] Talley and DeBarros, “China Aids Russia’s War in Ukraine, Trade Data Shows.”

[7] “Sanctioned Companies: Ulan-Ude Aviation Plant JSC,” War & Sanctions website.

[8] The first year of comprehensive international sanctions on Russian defense companies in response to the 2014 invasion of Ukraine was 2014.

[9] The first year of comprehensive international sanctions on Russian defense companies in response to the 2014 invasion of Ukraine was 2014.

[10] We detect warranty repair shipments by searching the goods descriptions for the words warranty or repair (ГАРАНТИЙНОГО, РЕМОНТА/РЕМОНТ) and manually check the results.

[11] Reported in the data originally as: “ИМУЩЕСТВО ДЛЯ ВЕРТОЛЕТА МАРКИ КА, ПОСТАВЛЕТСЯ ДЛЯ ВЫПОЛНЕНИЯ РЕМОНТА, КАТЕГОРИЯ ПРОДУКЦИИ ВОЕННОГО НАЗНАЧЕНИЯ 4.2.”

[12] Annual Investment Report, Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2021, CalPERS.