Pier Pressure

In the past three months, more than 80 high-risk distant water squid fishing vessels have landed in Chilean ports — an increase of more than 1,600 percent over years past, when the fleet primarily crowded the Peruvian exclusive economic zone.

When C4ADS released Keeping the Lights On in June 2025, we advised that the distant water squid fleet (DWSF) was adapting to oversight pressures in Peru. Just three months later, that prediction has borne out: the DWSF has all but abandoned its traditional Peruvian hub, while more than 80 high-risk squid vessels have landed in Chile. This shift south signals more than just a relocation. It brings with it a record of risk and regulatory abuse that Chile must now confront.

Unprecedented Arrivals #

Historically, Peru was the primary port of call for the DWSF, even after 2020 and 2024 legislation mandated the use of vessel monitoring system (VMS) to access port services.[1] Despite this, hundreds of squid vessels continued to land in Peru without the required VMS, often by invoking vague emergency requests for “forced arrival,” a practice reportedly never used by Chinese vessels before the 2020 legislation.[2] [3]

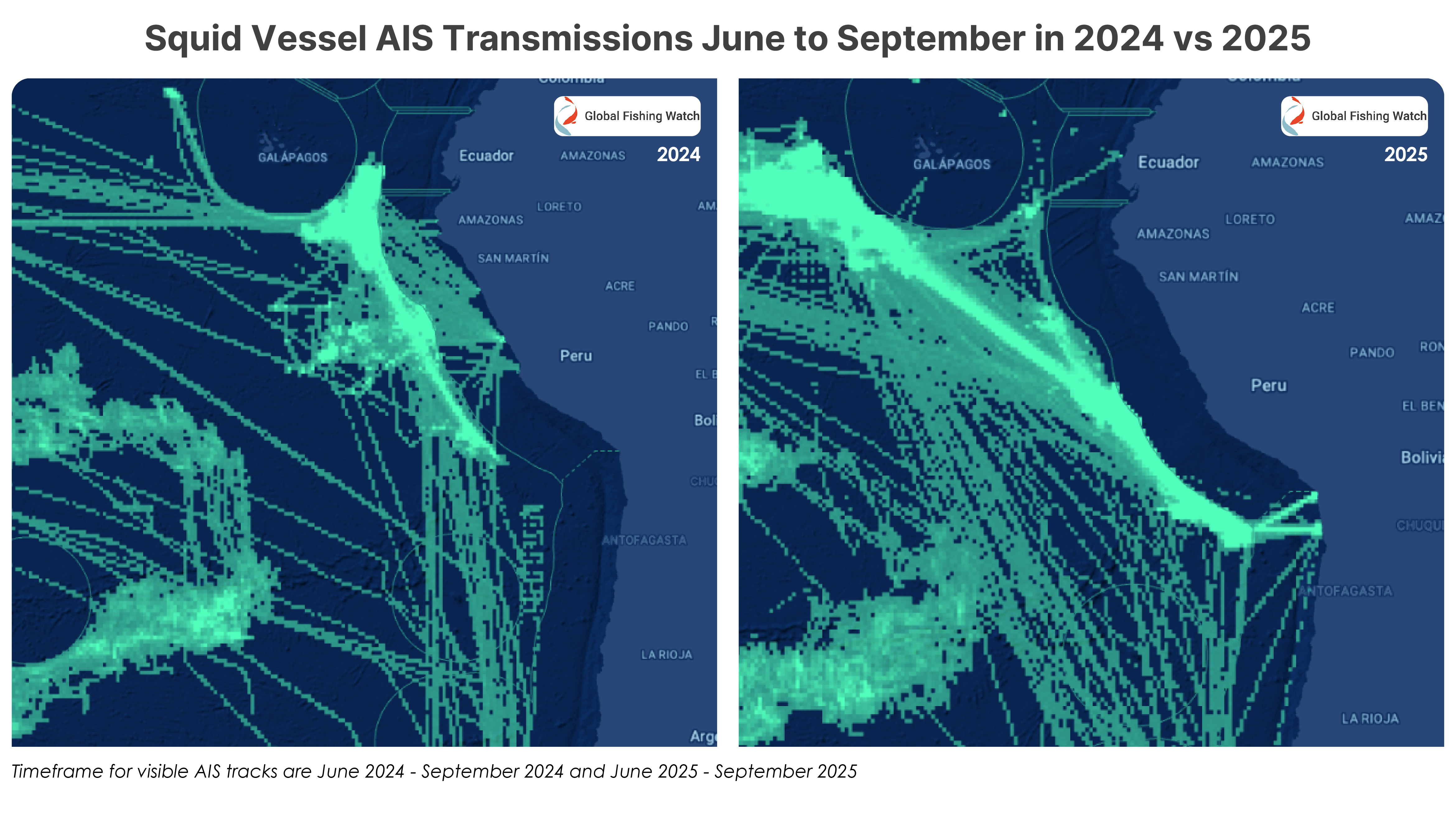

Chilean Port arrival records and AIS data indicate that port calls to Peru between June 1 and September 20 fell from more than 100 last year to 0 this year. As of the date of writing, not a single distant water squid vessel has landed in Peru.[4][5]

Instead, the fleet has shifted its movements south: In the last three months, over 80 distant water squid vessels have landed in Chilean ports including Arica, Iquique, Talcahuano, and Valparaiso. This marks a drastic increase from the nine squid vessels that landed in these ports in 2024. [6]

Eighty three of these 84 vessels had never landed in these specific ports before, according to analysis of AIS data. [7] For many, this was their first port call anywhere in Latin America in the previous 5 years. [8]

High Risk Vessels #

These vessels that landed in Chilean ports were previously identified by C4ADS as vessels of interest or part of fleets of interest tied to suspected or confirmed IUU fishing, forced labor, or other high-risk practices.[9]

Among these are nine vessels reportedly linked to or owned by Pingtan Marine Enterprise (PME), which has been sanctioned by the U.S. Treasury since December 2022, and its affiliated branch Juchangtai.[10] These vessels are not only landing at Chilean ports, but in some cases are also receiving services from Chilean state-owned shipyards.[11]

Familiar Enabling Networks #

C4ADS analysis shows that some of the fleet’s enabling actors have shifted with the vessels, picking up previous operations in the fleet’s new jurisdiction of choice.

Chief among them is Agental, a Chilean port agent previously spotlighted in Keeping the Lights On for facilitating high-risk port calls in Peru.[12] According to port records, the DWSF appears to still be using Agental as a preferred port agent while operating in Chile. [13]

Agental has been linked to a disproportionate number of arrivals involving sick, injured, or deceased crew in Peru, raising questions about its role in obscuring or enabling potentially dubious fleet practices. [14] The ease with which the DWSF shifted to Agental’s Chilean operations underscores the fixture of enabler networks, which provide the communications and logistical infrastructure that help high-risk actors to quickly pivot across jurisdictions.

Why It Matters #

Peru’s stricter oversight appears to have closed one door, but Chile, at least for now, has opened another. Without strengthened oversight and monitoring, Chile risks becoming the fleet’s “port of least resistance,” a hub for opaque and abusive operations.

This shift mirrors the resilience we’ve documented in companies like PME, which continue to operate despite U.S. sanctions through mutli-layered ownership, state subsidies, and enabling networks. [15] Geography shifts, but the playbook remains the same.

What’s Next? #

The fleet’s sudden relocation south puts Chile at the center of a challenge for South Pacific fisheries that, until now, was largely confined to Peru. What was once Peru’s burden of enforcement, inspections, and monitoring is now Chile’s to contend with. This shift also presents an opportunity to close oversight gaps and strengthen monitoring in a more integrated and sustainable way.

This season will provide the baseline data and momentum for Chile, its neighbors, and international partners to coordinate more effectively, offering Chilean authorities the chance to build on Peru’s lessons, close oversight gaps, and create a stronger regional framework for monitoring.

Will Chilean authorities apply stronger monitoring measures like VMS requirements, or has the fleet found an opportunity to evade oversight? For those of us watching the South Pacific squid season, the next few months will set the tone for whether Chile becomes a new hub for high-risk fleet operations, or a leader in ensuring greater transparency at sea.

[1]https://artis0nal.wixsite.com/my-site/en/post/what-is-the-distant-water-squid-fleet-hiding-to-resist-being-monitored

[2] https://apnews.com/article/fishing-peru-squid-forced-labor-9d839b6fa16c5f754cf10c4e3c433a19

[3]https://news.mongabay.com/2023/12/perus-ports-allow-entry-of-chinese-ships-tied-to-illegal-fishing-forced-labor/

[4] Global Fishing Watch

[5] https://sitport.directemar.cl/#/navpto

[6] Global Fishing Watch, Starboard Maritime Intelligence

[7] Global Fishing Watch

[8] Starboard Maritime Intelligence

[9] https://c4ads.org/reports/keeping-the-lights-on/

[10] https://c4ads.org/commentary/off-the-nasdaq/

[11] S&P Global AIS Reported Destination; SPRFMO Inspection Records

[12] https://c4ads.org/reports/keeping-the-lights-on/

[13] Port Arrival and Inspection Reports

[14] https://c4ads.org/reports/keeping-the-lights-on/

[15] https://c4ads.org/commentary/off-the-nasdaq/