Refining Power

Indonesia is on track to become the largest global producer of refined nickel, a mineral critical for everything from lithium-ion electric batteries to steel. But new C4ADS analysis shows that more than 75 percent of refining capacity in the country is controlled by Chinese stakeholders, many with ties to the CCP.

Introduction #

Indonesia, home to the world’s largest nickel reserves and a rapidly growing refining sector, will shape the future of green energy.[1] [2] Global demand for nickel—a key mineral used in steel and lithium-ion electric battery production—is projected to grow from around three million metric tons in 2023 to between five and six million metric tons by 2040, fueled primarily by the growth of clean energy technologies.[3] Yet in 2023, just two countries produced 65% of the world’s refined nickel: Indonesia and China.[4]

Global demand for nickel under current “stated policies scenario” for 2020 to 2040, by sector. Source: “Total nickel demand by sector and scenario, 2020-2040,” International Energy Agency, 2021, https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/charts/total-nickel-demand-by-sector-and-scenario-2020-2040.

Between 2020 and 2023, Indonesia’s share of the global refined nickel market grew from 23% to 27%, largely due to export bans on raw nickel in 2014 and 2020.[5] [6] By 2030, Indonesia is projected to account for 44% of the world’s refined nickel.[7]

However, much of this capacity is foreign-owned. Chinese companies or shareholders ultimately control at least 75% of Indonesia’s nickel refining capacity, but this is hidden behind layers of shell companies that mask foreign ownership.[8] [9] [10] U.S. and European Union automakers have only recently entered the industry, often by partnering with or sourcing from established Chinese companies, even as their governments grow increasingly cautious of Chinese dominance in critical supply chains.[11]

While the growth of Indonesia’s nickel refining industry has undoubtedly contributed to domestic economic development and job creation by adding value to the mineral domestically, it has also brought negative consequences, such as deforestation, pollution, and community health challenges.[12] [13] [14] The country’s nickel mostly comes from laterite ore deposits, which require substantially more energy to process into the high-grade, Class 1 nickel needed for EV batteries compared to the sulfide deposits in other countries.[15] Today, much of Indonesia’s nickel refining industry relies on coal-fired power plants, raising concerns about the use of fossil fuels to power the renewable energy transition.[16] [17]

Numerous reports have uncovered lax workplace safety within Indonesian processing facilities.[18] [19] [20] There have been several high-profile incidents in the past two years, and between 2015 and 2023, over 90 deaths and more than a hundred injuries have been reported in processing facilities.[21] Other investigations found that safety protocols in several smelters have been frequently ignored and accidents underreported.[22] In 2024, the U.S. Department of Labor added Indonesian nickel to its annual list of goods produced by forced labor.[23]

To effectively navigate this complex landscape and ensure ongoing accountability, it is crucial to identify the key players, understand their influence on the supply chain, and assess their responsibility for environmental and worker conditions.[24] This commentary maps the beneficial owners behind Indonesia’s nickel refining industry and its broader implications for the global energy market.

Methodology #

C4ADS identified 19 nickel refineries responsible for over 90% of Indonesian nickel production capacity in 2023 using data from Indonesia’s Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources. Note this analysis is based on capacity, not current production levels. C4ADS next identified the corporate ownership for these companies using official corporate registries and third-party aggregators. Each company or shareholder’s share of production capacity was calculated by multiplying the share in ownership of the company by the smelter’s share of total capacity.

Ownership #

Indonesia’s eight million metric ton nickel refining capacity (as of 2023) initially appears to be distributed across 33 companies.[25] However, ownership tracing reveals there is significant concentration in foreign countries and substantial overlap in shareholders.[26] [27] When ownership is traced to the second level, Chinese companies or shareholders control 61% of the refining capacity, while Indonesian companies or shareholders control just 13%. Further tracing uncovers that Chinese beneficial ownership exceeds 75%.[28] [29] As Indonesia aims to use the nickel industry for economic growth, this substantial foreign influence could limit its ability to control and shape the industry for its benefit.

Foreign shareholder control of Indonesia’s 2023 nickel refining capacity separated by layers of ownership. Inner circle represents first layer of ownership, and outer circle represents second layer of ownership. Country of ownership was determined by company registration location. Source: Author’s calculations based on data from PT Citra Cendekia Indonesia, Wirescreen, and corporate records.

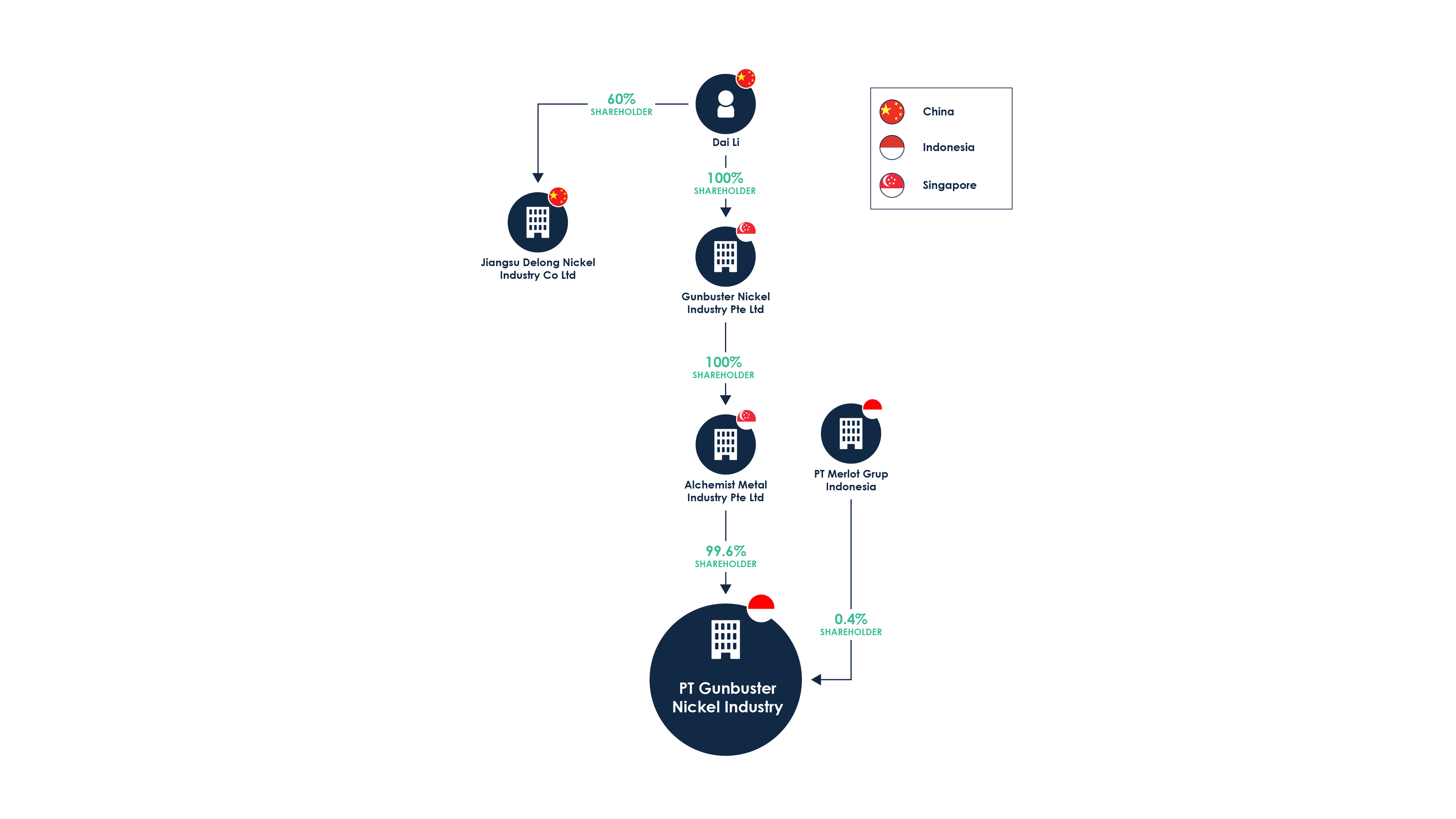

The ownership structures of these top companies are often complex, with Chinese involvement masked behind layers of corporate entities registered in different countries.[30] For example, corporate records disclose that PT Gunbuster Nickel Industry, which accounts for just over 5% of Indonesia’s refining capacity, is primarily owned by a company registered in Singapore.[31] [32] Tracing such publicly available records back further, the company is ultimately controlled by Dai Li, who is also the majority shareholder of Jiangsu Delong Nickel Industry Company Ltd, a Chinese company with significant ownership ties to Indonesia’s two largest smelters: PT Virtue Dragon Nickel Industry and PT Obsidian Stainless Steel.[33] [34]

Ownership Network of PT Gunbuster Nickel Industry

Source: Author’s calculations based on Wirescreen and corporate records.

Several of the Chinese companies involved in Indonesia’s nickel refining industry have connections to the People’s Republic of China government or have benefited from substantial financial backing from Chinese banks.[35] [36] For example, the People’s Government of the Guangdong Province and the Department of Finance of Guangdong Province, two Chinese government entities, together ultimately own the largest share of the Indonesian registered refining company, PT Guang Ching Nickel and Stainless Steel Industry.[37]

Ownership Network of PT Guang Ching Nickel & Stainless Steel Industry

Source: Author’s calculations based on Wirescreen and corporate records.

PT Indonesia Tsingshan Stainless Steel, which accounts for over 7% of Indonesia’s refining capacity, reportedly received initial loans from the China Development Bank and Bank of China worth over US$570 million to finance its efforts.[38] [39] Such financial support gives it a competitive edge that the United States and other international competitors struggle to match.[40]

China’s early investment in Indonesia’s nickel industry has positioned it as a dominant player for years to come.[41] This strategic move ensures a supply of cheap nickel for China’s EV manufacturing sector and gives China greater control over prices going forward.[42] Between January 2023 and July 2024, the price of nickel fell by 47% following a surge in Indonesian production.[43] On one hand, this benefits Chinese and other EV manufacturers with cheap material, but on the other hand, it raises the barrier to entry for competitors and poses financial challenges for refining companies that have less capital to withstand price fluctuations.

Key Chinese Companies #

Public records indicate that two Chinese companies have considerable shares in refineries that account for over 70% of Indonesia’s nickel refining capacity: Tsingshan Holding Group and Jiangsu Delong Nickel Industry Co Ltd.[44] [45] Not only does this ownership concentration raise concerns about industry dominance, but these two companies have also been associated with significant environmental and social issues.

Case Study: Tsingshan Holding Group #

Tsingshan Holding Group (Tsingshan) is known as the world’s largest stainless steel producer and is a major force in Indonesia’s nickel industry.[46] Its investment in Indonesia dates to at least 2009, when the company reportedly invested in the development of Indonesia’s laterite ore mines.[47] Today, records show that Tsingshan holds shares in at least five of the major nickel smelting companies in Indonesia, including the third-largest smelter.[48] [49]

Tsingshan Holding Group’s Ownership Stake in Nickel Refining Companies in Indonesia and Links to PT Indonesia Morowali Industrial Park

Note: Chart may not encompass all of Tsingshan Holding Group’s operations in the sector. Source: Author’s calculations based on Wirescreen and corporate records

One of Tsingshan’s most prominent holdings in Indonesia is PT Indonesia Morowali Industrial Park (PT IMIP).[50] PT IMIP is a nickel refining industrial park that houses over 54 companies, employs more than 80,000 people, and is listed as one of Indonesia’s National Strategic Projects.[51] Public reporting indicates that the initial US$1.22 billion investment for PT IMIP came from the China Development Bank in 2018, which the State Council of China oversees and uses to support China’s economic development in key industries, suggesting Chinese financial and state interest in Indonesia’s nickel industry.[52] [53]

There is substantial reporting that PT IMIP’s operation and construction have had significant negative environmental effects.[54] The local community reports general water pollution from PT IMIP’s activities, an increase in the water temperature due to the direct release of exhaust from the park’s cooling systems, particulate pollution from the coal-fired power plants used to power the park, and species loss.[55]According to the nonprofit Mighty Earth, PT IMIP is expected to have an annual coal-fired power capacity of 5GW, which is equivalent to the country of Mexico’s entire capacity.[56] Furthermore, over 8,700 hectares (33 square miles) of land was reportedly cleared to make space for PT IMIP.[57] Deforestation from this and other projects has led to severe flooding in the nearby community, destroying homes and local infrastructure.[58]

Aerial Footage of PT Indonesia Morowali Industrial Park. Source: Mas Agung Wilis, 2024

Journalists examining workplace safety incidents across Tsingshan’s operations since 2023 revealed numerous reports of small- and large-scale workplace injuries. Workers reported widespread failures such as inadequate protective equipment, poor communication, and lax safety practices.[59]

In 2023, at least 60 deaths or accidents were reportedly linked to Tsingshan, including a fire that killed 21 individuals and injured 38 at PT Indonesia Tsingshan Stainless Steel.[60] [61] Indonesian government officials were quoted saying that there were “strong indications” of violations in procedures and negligence of safety requirements leading to the fire and named two Chinese nationals who were in charge of the furnace as suspects.[62] [63] In March 2024, 40 employees at PT IMIP reported suffering from shortness of breath following an acid leak at a PT Merdeka Tsingshan Indonesia plant.[64] A few months later in June, two workers reportedly received intensive care after suffering injuries from a burst of hot vapor at one of PT Indonesia Tsingshan Stainless Steel’s smelter furnace areas.[65] In addition, according to China Labor Watch, workers within PT IMIP reported facing issues such as “wage withholdings, illegal contracting practices, workplace injuries and deaths, dangerous conditions, abuse, and an overall culture of silence.” [66] These examples are just a small sample of some of the workplace atrocities associated with operations conducted by Tsingshan in Indonesia.

Video of a smelter fire at PT IMIP in August 2024 Source: Confidential Source

Case Study: Jiangsu Delong Nickel #

Jiangsu Delong Nickel Industry Co., Ltd. (Jiangsu Delong Nickel) is a large Chinese stainless steel company that appears to have initially invested in Indonesia in 2015 and has since emerged as an industry powerhouse.[67]

Business records show that Jiangsu Delong Nickel has significant ownership stakes in three of the top refining companies: PT Virtue Dragon Nickel Industry, PT Obsidian Stainless Steel, and PT Gunbuster Nickel Industry. When combined, these three companies account for over 38% of Indonesia’s 2023 nickel refining capacity.[68] [69]

Jiangsu Delong Nickel’s Ownership Stake in Nickel Refining Companies in Indonesia and Links to Chinese Contractors and State-Owned Enterprises

Note: Chart may not encompass all of Jiangsu Delong Nickel Industry’s operations within the sector. Source: Author’s calculations based on Wirescreen and corporate records.

According to Indonesia’s Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources, PT Virtue Dragon Nickel Industry (Virtue Dragon) has the largest refining capacity in Indonesia with the ability to produce 1.6 million metric tons of ferronickel and nickel pig iron per year, accounting for over 19% of the country’s capacity.[70] [71] Wirescreen data indicates that one of Virtue Dragon’s other major shareholders, Sino Virtue International Development, is ultimately owned by China First Heavy Industries, a major Chinese state-owned enterprise with ties to the Chinese military through defense contracting.[72]

PT Obsidian Stainless Steel accounts for over 14% of Indonesia’s nickel refining capacity, and PT Gunbuster Nickel Industry accounts for over 5%.[73] Corporate records indicate that PT Obsidian Stainless Steel is ultimately 51% owned by Xiamen Xiangyu Group Corporation, a Chinese state-owned enterprise. As previously noted, PT Gunbuster Nickel Industry’s ultimate ownership appears to be masked behind three layers of corporate ownership.[74]

Jiangsu Delong Nickel’s operations have also been associated with a number of environmental issues and concerns. An investigation by Mongabay reported that Virtue Dragon and PT Obsidian Stainless Steel’s coal-fired power plants reportedly polluted over 16 million square feet of fishponds owned by locals, threatening their livelihoods.[75] Mongabay also reported that when PT Gunbuster Nickel Industry built its coal-fired power plant, it dammed a local river which caused flooding in the nearby community.[76]

The local community has highlighted concerns over lax workplace safety standards within Jiangsu Delong Nickel’s operations.[77] In January 2023, two workers died at a protest at PT Gunbuster Nickel Industry over labor conditions as well as numerous documented accidents and deaths within Jiangsu Delong Nickel’s operations.[78] Trend Asia reported that, between 2015 and 2022, Jiangsu Delong Nickel’s operations were associated with at least 12 accidents, nine deaths, and five injuries.[79] Despite growing attention to safety issues, China Labor Watch reported that, in 2023, Jiangsu Delong Nickel’s operations had four separate documented incidents, including a vehicle accident, a fall from an elevated surface, and two fires that killed at least two individuals and injured six more.[80] These statistics likely represent only a fraction of the actual incidents, as workplace accidents often go unreported.

High Grade Nickel Refining #

Indonesia’s nickel industry continues to evolve in parallel with the demand for nickel, presenting an opportunity to address many of its issues.

Refined nickel is divided into two main classes: Class I and Class II. Class I nickel is a higher-grade nickel, mainly used in EV batteries. Class II nickel is a lower-quality nickel, mainly used in stainless steel production.[81] While Indonesia’s current refining industry, including the operations of Tsingshan and Jiangsu Delong Nickel, predominantly produce Class II nickel, there has been a recent push for the development of Class I refining operations.[82] [83] Class II nickel can become Class I nickel through additional refining. With the increased global demand for Class I nickel, this may become more common.[84]

Ownership tracing for Class I operations reveals a landscape similar to that of Class II nickel: an industry dominated by foreign companies, primarily with Chinese ultimate beneficial ownership.[85] [86] [87]

Class I nickel refining also comes with additional important environmental considerations. Most notable are concerns surrounding the storage of tailings, the toxic byproduct produced during refining.[88] Currently, tailings are often left to dry in the open air or returned to open mines, but this can produce toxic waste that pollutes waterways and harms nearby communities, especially in Indonesia’s tropical climate.[89] An alternative to open-air disposal is deep-sea disposal, which would threaten the vital and biodiverse coral triangle in Southeast Asia.[90] On top of that, the refining processes to reach Class I nickel is more energy intensive than refining for Class II nickel, which, in turn, further increases the demand for coal.[91]

Conclusion #

The concentration of Indonesia’s refined nickel supply chain in a handful of companies—many with connections to Chinese state-owned enterprises—will have multiple long-term ramifications.

It will be challenging for other countries to meet domestic demand without access to Indonesian nickel. China’s entrenched position in the industry makes it difficult for companies to establish a fully independent and secure supply chain outside of China. The reliance on Chinese-controlled nickel production not only raises concerns about supply chain resilience, but also places U.S. and European automakers at a competitive disadvantage in the global EV market amid increasingly restrictive policies against trade with China. These competing pressures have the potential to hinder innovation, delay production timelines, and disrupt supply.

To safeguard the nickel supply chain amid an ever-changing geopolitical landscape, transparency, accountability, and decentralization will be pivotal challenges for policymakers and corporate actors to overcome.

[1] “Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2024,” International Energy Agency, https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/ee01701d-1d5c-4ba8-9df6-abeeac9de99a/GlobalCriticalMineralsOutlook2024.pdf, accessed October 2024.

[2] Ayman Falak Medina, “Unleashing Nickel’s Potential: Indonesia’s Journey to Global Prominence,” Dezan Shira & Associates, May 30, 2023, https://www.aseanbriefing.com/news/unleashing-nickels-potential-indonesias-journey-to-global-prominence/.

[3] “Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2024,” International Energy Agency.

[4] “Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2024,” International Energy Agency.

[5] “Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2024,” International Energy Agency.

[6] Isabelle Huber, “Indonesia’s Nickel Industrial Strategy” Center for Strategic and International Studies, December 8, 2021, https://www.csis.org/analysis/indonesias-nickel-industrial-strategy

[7] “Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2024,” International Energy Agency.

[8] PT Citra Cendekia Indonesia, “Industry and Market Prospect of Nickel Processing in Indonesia,” Bizteka Industry & Commodity, NO ISSN: 2540-9603, June 2023;

[9] Wirescreen/Corporate Records.

[10] Antonia Timmerman, Lucy Stevenson-Yang, and Chi Yuan, “Nickel Nexus: Indonesia’s China-Backed Nickel-To-Battery Ambition,” China Global South Project, September 2024, https://chinaglobalsouth.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Report-004-Nickel-2024-09-11-web-1.pdf.

[11] Rick Mills, “Indonesia and China Killed the Nickel Market,” Mining.com, March 04, 2024, https://www.mining.com/web/indonesia-and-china-killed-the-nickel-market/.

[12] Valdya Baraputri, “The rush for nickel: ‘They are destroying our future’,” BBC News, July 09, 2023, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-66131451.

[13] Rebecca Tan, Dera Menra Sijabat, and Joshua Irwandi, “To meet EV demand, industry turns to technology long deemed hazardous,” Washington Post, May 10, 2024, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/interactive/2023/ev-nickel-refinery-dangers/.

[14] Matthew Campbell and Annie Lee, “The Deadly Mining Complex Powering the EV Revolution” Bloomberg, June 17, 2024, https://www.bloomberg.com/features/2024-indonesia-sulawesi-nickel-fire/?sref=OrVjKRhh

[15] “GHG emissions intensity for class 1 nickel by resource type and processing route,” International Energy Agency, May 05, 2021,

[16] Rodrigo Castillo, Lilly Blumenthal, and Caitlin Purdy, “Indonesia’s electric vehicle batteries dream has a dirty nickel problem,” Brookings, September 21, 2022, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/indonesias-electric-vehicle-batteries-dream-has-a-dirty-nickel-problem/.

[17] Castillo, Blumenthal, and Purdy, “Indonesia’s electric vehicle batteries dream has a dirty nickel problem.”

[18] Baraputri, “The Rush for Nickel: They are destroying our future.”

[19] Tan, Dera Menra Sijabat, and Irwandi, “To meet EV demand, industry turns to technology long deemed hazardous.”

[20] Matthew Campbell and Annie Lee, “The Deadly Mining Complex Powering the EV Revolution”

[21] Workplace Accident: Neglect and Violation of Employee Rights in Indonesia Nickel Industrial Areas,” Trend Asia, March 13, 2023, https://trendasia.org/en/workplace-accident-neglect-and-violation-of-employee-rights-in-indonesia-nickel-industrial-areas/.

[22] Anantha Lakshmi and Diana Mariska, “‘Production first, safety later’: inside the world’s largest nickel site,” Financial Times, November 28, 2024, https://www.ft.com/content/56013ee9-f456-4646-895c-aeb65a685f85.

[23] Government of the United States, 2024 List Of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor, Office of Child Labor, Forced Labor, and Human Trafficking, 2023),https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/ilab/child_labor_reports/tda2023/2024-tvpra-list-of-goods.pdf.

[24] “Just Transition for All: The World Bank Group’s Support to Countries Transitioning Away from Coal,” World Bank, https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/extractiveindustries/justtransition, accessed December 01, 2024.

[25] PT Citra Cendekia Indonesia, “Industry and Market Prospect of Nickel Processing in Indonesia,”

[26] PT Citra Cendekia Indonesia, “Industry and Market Prospect of Nickel Processing in Indonesia,”

[27] Wirescreen and Corporate Records

[28] PT Citra Cendekia Indonesia, “Industry and Market Prospect of Nickel Processing in Indonesia.”

[29] Wirescreen and Corporate Records

[30] Antonia Timmerman, Lucy Stevenson-Yang, and Chi Yuan, “Nickel Nexus: Indonesia’s China-Backed Nickel-To-Battery Ambition,”

[31] PT Citra Cendekia Indonesia, “Industry and Market Prospect of Nickel Processing in Indonesia.”

[32] Wirescreen and Corporate Records

[33] PT Citra Cendekia Indonesia, “Industry and Market Prospect of Nickel Processing in Indonesia.”

[34] Wirescreen and Corporate Records

[35] Wirescreen and Corporate Records

[36] Angelo Tritto, “How Indonesia Used Chinese Industrial Investments to Turn Nickel into the New Gold,” Carnegie Europe, April 11, 2023, https://carnegieindia.org/research/2023/04/how-indonesia-used-chinese-industrial-investments-to-turn-nickel-into-the-new-gold?lang=en¢er=europe. d

[37] PT Citra Cendekia Indonesia, “Industry and Market Prospect of Nickel Processing in Indonesia,”.

[38] PT Citra Cendekia Indonesia, “Industry and Market Prospect of Nickel Processing in Indonesia,”.

[39] Arianto Sangadji and Pius Ginting, “Multinational Corporations and Nickel Downstreaming in Indonesia,” Perkumpulan Aksi Ekologi dan Emansipasi Rakyat (AEER), September 2023, https://www.aeer.or.id/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Arianto_Sangadji_25_Juli_2023-Layouted.pdf.

[40] Antonia Timmerman, Lucy Stevenson-Yang, and Chi Yuan, “Nickel Nexus: Indonesia’s China-Backed Nickel-To-Battery Ambition,”

[41] Tritto, “How Indonesia Used Chinese Industrial Investments to Turn Nickel into the New Gold,”

[42] Mills, “Indonesia and China Killed the Nickel Market,”

[43] Tim Treadgold, “Indonesia has a China Problem in its Nickel Industry,” Forbes, July 30, 2024, https://www.forbes.com/sites/timtreadgold/2024/07/29/indonesia-has-a-china-problem-in-its-nickel-industry/#:~:text=The%20flood%20of%20nickel%20from,particularly%20good%20for%20Indonesian%20miners.

[44] PT Citra Cendekia Indonesia, “Industry and Market Prospect of Nickel Processing in Indonesia,”.

[45] Wirescreen and Corporate Records.

[46] Tritto, “How Indonesia Used Chinese Industrial Investments to Turn Nickel into the New Gold,”

[47] Aiqun Yu, “Case Study: Tsingshan Industrial Parks in Indonesia Post-China’s Coal Pledge,” Energy Tracker Asia, November 30, 2021, https://energytracker.asia/tsingshan-industrial-park-in-indonesia-case-study/.

[48] PT Citra Cendekia Indonesia, “Industry and Market Prospect of Nickel Processing in Indonesia,”.

[49] Wirescreen and Corporate Records.

[50] Tritto, “How Indonesia Used Chinese Industrial Investments to Turn Nickel into the New Gold.”

[51] Pius Ginting and Ellen Moore, “Indonesia Morowali Industrial Park (IMIP),” The People’s Map of Global China, November 22, 2021, https://thepeoplesmap.net/project/indonesia-morowali-industrial-park-imip/.

[52] Ginting and Moore, “Indonesia Morowali Industrial Park (IMIP),” The People’s Map of Global China.

[53] “About CDB” China Development Bank, https://www.cdb.com.cn/English/gykh_512/khjj/

[54] Antonia Timmerman, “The Dirty Road to Clean Energy: How China’s Electric Vehicle Boom is Ravaging the Environment,” Rest of World, November 28, 2022, https://restofworld.org/2022/indonesia-china-ev-nickel/; https://imip.co.id/.

[55] Timmerman, “The Dirty Road to Clean Energy.”

[56] David Brown and Jackson Harris, “From Forests to Electric Vehicles,” Mighty Earth, 2024, https://mightyearth.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/FromForeststoEVs.pdf.

[57] Peter Yeung, Workers Are Dying in the EV Industry’s ‘Tainted’ City,” Wired/Pulitzer Center, February 20, 2023, https://pulitzercenter.org/stories/workers-are-dying-ev-industrys-tainted-city.

[58] Arianto Sangadji and Pius Gingting, “Multinational Corporations and Nickel Downstreaming in Indonesia, AEER, September 2023, https://www.aeer.or.id/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Arianto_Sangadji_25_Juli_2023-Layouted.pdf.

[59] Anantha Lakshmi and Diana Mariska, “‘Production first, safety later’: inside the world’s largest nickel site,” Financial Times, November 28, 2024, https://www.ft.com/content/56013ee9-f456-4646-895c-aeb65a685f85.

[60] China Labor Watch, shared dataset.

[61] “Indonesia nickel smelter furnace fire kills 13 workers, injures 46,” Reuters, December 24, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/smelter-furnace-blast-kills-12-indonesias-morowali-nickel-industrial-park-media-2023-12-24/.

[62] “Indonesia says ‘strong indication’ of safety violation led to fire at Chinese-owned nickel plant that killed 21 people,” South China Morning Post, January 16, 2024, https://www.scmp.com/news/asia/southeast-asia/article/3248665/indonesia-says-strong[…]safety-violation-led-fire-chinese-owned-nickel-plant-killed-21.

[63] “Indonesia Police Seek 2 Chinese Suspects in Nickel Plant Explosion,” Voice of America, February 12, 2024, https://www.voanews.com/a/indonesia-police-seek-2-chinese-suspects-in-nickel-plant-explosion-/7484735.html.

[64] “Repeated Work Accidents, Gunhar Asks for Thorough Investigation at PT IMIP Morowali,” JPNN, March 26, 2024, https://www.jpnn.com/news/40-karyawan-meninggal-gunhar-minta-investigasi-menyeluruh-di-pt-imip-morowali.

[65] “Another Explosion at Indonesian Nickel Plant Injures Workers,” Industri All Global Union, June 26, 2024, https://www.industriall-union.org/another-explosion-at-indonesian-nickel-plant-injures-workers.

[66] “Forged in Silence – The Untold Stories of Chinese Workers at Indonesia’s Nickel Plants,” China Labor Watch, June 28, 2024,

[67] Wirescreen

[68] PT Citra Cendekia Indonesia, “Industry and Market Prospect of Nickel Processing in Indonesia,”

[69] Wirescreen and Corporate Records

[70] PT Citra Cendekia Indonesia, “Industry and Market Prospect of Nickel Processing in Indonesia,”

[71] Wirescreen and Corporate Records.

[72] Wirescreen and Corporate Records.

[73] PT Citra Cendekia Indonesia, “Industry and Market Prospect of Nickel Processing in Indonesia,”.

[74] P Wirescreen and Corporate Records.

[75] Hans Nicolas Jong, “Activists slam coal pollution from Indonesia’s production of ‘clean’ batteries,” Mongabay, August 23, 2023, https://news.mongabay.com/2023/08/activists-slam-coal-pollution-from-indonesias-production-of-clean-batteries/.

[76] Jong, “Activists slam coal pollution from Indonesia’s production of ‘clean’ batteries.”

[77] China Labor Watch, shared dataset.

[78] Bernadette Christina and Ananda Teresia, “Indonesia deploys security forces after nickel smelter protest turns deadly” Reuters, January 16, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/violence-indonesia-nickel-smelter-protest-kills-2-dozens-detained-2023-01-16/

[79] “Workplace Accident: Neglect and Violation of Employee Rights in Indonesia Nickel Industrial Areas,” Trend Asia, March 13, 2023, https://trendasia.org/en/workplace-accident-neglect-and-violation-of-employee-rights-in-indonesia-nickel-industrial-areas/.

[80] China Labor Watch, shared dataset.

[81] Rodrigo Castillo, Lilly Blumenthal, and Caitlin Purdy, “Indonesia’s electric vehicle batteries dream has a dirty nickel problem,” Brookings, September 21, 2022, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/indonesias-electric-vehicle-batteries-dream-has-a-dirty-nickel-problem/.

[82] PT Citra Cendekia Indonesia, “Industry and Market Prospect of Nickel Processing in Indonesia,”.

[83] Wirescreen and Corporate Records

[84] Castillo, Blumenthal, and Purdy, “Indonesia’s electric vehicle batteries dream has a dirty nickel problem.”

[85] PT Citra Cendekia Indonesia, “Industry and Market Prospect of Nickel Processing in Indonesia,”

[86] Wirescreen and Corporate Records.

[87] Brown and Harris, “From Forests to Electric Vehicles.”

[88] David Brown and Jackson Harris, “From Forests to Electric Vehicles,” Mighty Earth, 2024, https://pulitzercenter.org/stories/workers-are-dying-ev-industrys-tainted-city.

[89] Brown and Harris, “From Forests to Electric Vehicles.”

[90] Brown and Harris, “From Forests to Electric Vehicles.”

[91] Castillo, Blumenthal, and Purdy, “Indonesia’s electric vehicle batteries dream has a dirty nickel problem.”