In Plane Sight

In Plane Sight examines wildlife trafficking through the air transport sector by analyzing nine years’ worth of open source seizure information, and is intended to provide an update on wildlife trafficking activity in airports since last year’s Flying Under the Radar. Over the past year, C4ADS analysts have continued to collect ivory, rhino horn, reptile, and bird seizures, and have developed three new datasets covering pangolin, marine products, and mammal seizures.

In general, the report finds wildlife trafficking activity to be truly global in scope, and increasingly so, as trafficking networks continue to seek out new source regions and demand markets for their illicit products.

Executive Summary #

Wildlife traffickers are benefiting from an increasingly interconnected world. As marketplaces have become progressively more international, wildlife trafficking networks have been able to exploit the advance of technology, profiting off the development of the international financial system and increasingly intertwined transportation networks. By 2016, environmental crime had grown into a multi-billion dollar industry, worth as much as $91 to $258 billion annually, with wildlife crime specifically making up $7 to $23 billion of the total.

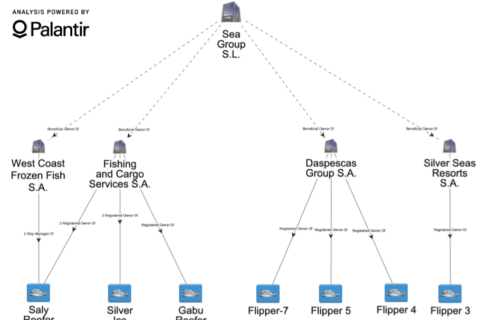

But while wildlife criminal networks were learning to take advantage of finance and transportation networks, they made a mistake: they became dependent on them. Wildlife criminal groups now rely on international systems of trade, finance, and transport to make a profit, forcing them to emerge from behind their carefully constructed disguises to engage with the lawful, regulated world, thus exposing themselves to discovery.

Wildlife seizures are the clearest outward sign of this weakness. If carefully collected, stored, and analyzed, wildlife seizure data can reveal a great deal about wildlife trafficking trends, routes, and methods, including how wildlife networks seem to respond to different enforcement and market pressures. In Plane Sight examines wildlife trafficking through the air transport sector by analyzing nine years’ worth of open source seizure information, and is intended to provide an update on wildlife trafficking activity in airports since last year’s Flying Under the Radar.

Unhindered by laws, regulations, or bureaucracy, criminal networks are creative and evolve quickly, generally outpacing enforcement, which remains perpetually a step behind. Ultimately, large-scale disruption of wildlife criminal networks requires shifting alongside them, identifying new trafficking methods as they arise, and overtaking them by anticipating their responses to enhanced enforcement activity and preparing accordingly.

Over the past year, C4ADS analysts have continued to collect ivory, rhino horn, reptile, and bird seizures, and have developed three new datasets covering pangolin, marine products, and mammal seizures. Together, these seven categories account for about 81% of known trafficked wildlife, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC).3 Although seizure data can present a slightly inaccurate view of wildlife trafficking, if considered with the appropriate caveats, it provides the best available picture of overall trafficking activity and can be used to direct future anti-trafficking efforts.

This report is divided into the seven different wildlife categories included in the C4ADS Air Seizure Database. The analysis in each section is broken down into smaller subsections that review, in order: overall trafficking trends, trafficking routes, and trafficking methods. The first four sections (ivory, rhino horn, reptiles, and birds) focus primarily on 2017 data, while the next three sections (pangolins, marine products, and mammals) cover 2009 through 2017. The wildlife category sections are followed by five appendices, which include:

- an analysis of WCO CEN wildlife seizure data,

- an analysis of FWS LEMIS seizure data,

- annual trafficking route maps (2015 through 2017) for each wildlife category,

- a Human Trafficking Assessment Tool for the air transport sector,

- a seizure reporting template,

- the R packages used to create the graphics for this report.

In general, this report finds wildlife trafficking activity to be truly global in scope, and increasingly so, as trafficking networks continue to seek out new source regions and demand markets for their illicit products.