Hooked

Once essential to the economy of the Gulf of California in Mexico, the totoaba fish has suffered a precipitous decline over the past century due to overfishing. The problem reached its zenith in the 1970s, resulting in a ban on totoaba fishing, and the species’ receipt of the highest levels of protection under Mexican, U.S., and international law. After a few decades of comparative calm, the totoaba is under attack once again. Illegal fishermen hoping to amass a few kilograms of the totoaba’s famed bladders–potentially earning them over a year’s salary in a single night–are destabilizing the remaining totoaba population.

But the totoaba’s high value signals trouble for more than just the continued viability of the species; the nets used to catch them, called gillnets, are devastating marine life in the Gulf. One species in particular, the vaquita, the world’s smallest porpoise species, has suffered disproportionately from the resurgence of totoaba poaching. A reclusive and shy animal, the vaquita have suffered substantial losses at the hands of totoaba poachers, declining from 567 individuals in 1997 to an estimated 26 by May 2017.

Executive Summary #

Once essential to the economy of the Gulf of California in Mexico, the totoaba fish has suffered a precipitous decline over the past century due to overfishing. The problem reached its zenith in the 1970s, resulting in a ban on totoaba fishing, and the species’ receipt of the highest levels of protection under Mexican, U.S., and international law. After a few decades of comparative calm, the totoaba is under attack once again. Illegal fishermen hoping to amass a few kilograms of the totoaba’s famed bladders – potentially earning them over a year’s salary in a single night – are destabilizing the remaining totoaba population.

But the totoaba’s high value signals trouble for more than just the continued viability of the species; the nets used to catch them, called gillnets, are devastating marine life in the Gulf. One species in particular, the vaquita, the world’s smallest porpoise species, has suffered disproportionately from the resurgence of totoaba poaching. A reclusive and shy animal, the vaquita have suffered substantial losses at the hands of totoaba poachers, declining from 567 individuals in 1997 to an estimated 26 by May 2017. With illegal totoaba fishing showing no signs of decreasing – some evidence suggests that totoaba fishermen have only become more brazen – and despite a gillnet ban, gillnet removal operations, and other programs, the vaquita face a dark future without an immediate and substantial change.

Compounding the problem (and further imperiling the vaquita), organized criminal networks entered the totoaba trafficking scene in about 2013, attracted by the prospect of a little-known fish bladder worth as much as its weight in cocaine.i Their entrance signaled the arrival of a period of volatility and insecurity in the region, as criminal bosses jockeyed to control the totoaba trade in seaside towns and cities, and criminal fishermen began to use their law-abiding counterparts as a smokescreen for illegal activity.

Mexican authorities have struggled to address the problem, with little help from foreign governments who recognize totoaba trafficking as a conservation problem, but not a major criminal or security issue. In the meantime, organized criminal groups have solidified their hold on the totoaba trade in the Gulf, corrupting those officials who stand in their way (even those who proved resistant to the corrupting influence of narcotics traffickers), and frightening the local populations into silence.

Without a concerted, international effort to loosen their grip and reverse the devastation wrought on the Gulf of California, the totoaba and the vaquita could both be lost. Organized criminal actors will then turn to some other high-value crime. Newly minted totoaba traffickers may join them, unwilling – and perhaps unable – to return to the unassuming, often difficult life of a legal fisherman.

Hooked examines the totoaba trafficking supply chain, from the Gulf of California, through the United States, and into Chinese destination markets. The report is broken down into the following sections:

- Fishing briefly examines the history of totoaba fishing and panga activity in the Gulf, and traces the origins of the current crisis. Recent gillnet retrieval data is used to shed light on fluctuations in illegal fishing activity, and the modus operandi of totoaba fishermen are described in detail. Finally, the recent involvement of organized criminal groups in totoaba fishing – and the resulting impact on regional stability and security – is revealed.

- Trafficking follows the totoaba supply chain from the Gulf of California to Chinese destination markets, beginning with the methods used to move totoaba bladders from the shores of the Gulf to consolidation and processing points. Trafficking methods and routes between Mexico, the United States, and Asia are exposed, and various possible explanations are given for the recent decline in identifiable totoaba trafficking activity, despite little to no observed changes in illegal totoaba fishing.

- Destination first describes known and suspected trafficking methods between the Americas and Asia, as well as between Hong Kong and mainland China. The significant drop in totoaba prices and overt market activity since 2012 are assessed, and the still thriving online trade for totoaba bladders is analyzed.

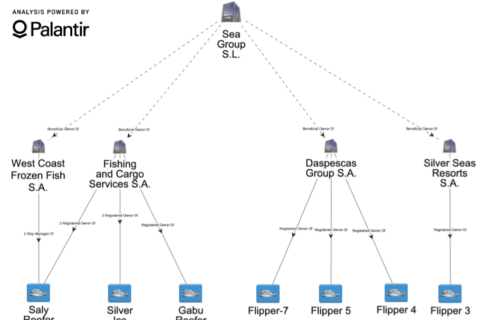

Finally, C4ADS identified a number of small-scale networks moving totoaba from the Gulf of California to Asia, occasionally passing through the United States on the way. C4ADS found that even in cases where networks could not be identified, common modus operandi associated with the illicit totoaba trade were highly suggestive of organized criminal activity, rather than opportunistic fishing by a small sub-set of local fishermen. A number of cases given slight coverage in the Mexican press, and almost no coverage beyond the Gulf of California area, cast light on the links between the totoaba trade and other crime types, and highlight the need to address totoaba trafficking as the organized crime it has become.

The totoaba trafficking crisis has escalated to the point that Mexican authorities cannot fix the problem alone; additional support – from other governments, NGOs, and the international community – is desperately needed. Continuing to think of totoaba trafficking as only a conservation issue ignores the clear security implications it has and could have for Mexico and the United States, including the long-term destabilization of the Baja California region. Surely addressing the problem now, and perhaps saving the vaquita, is preferable to watching the biodiversity of the Gulf continue to decline, and in so doing, driving the further deterioration of the Gulf economy and allowing for the insidious expansion of Mexican organized crime’s already substantial reach and power