Beyond the Scales

Recent reporting on the COVID-19 (coronavirus) outbreak that originated in Wuhan, China suggests that the world’s most trafficked mammal – the pangolin – may have been the intermediate carrier of the virus from bats to humans. While experts continue to collect evidence and determine the epidemiology of the virus, China has banned the consumption of wild animals, which would include pangolins. The ban recognizes the link between the consumption of wild animals and the spread of novel diseases. However, for this ban to positively impact the vulnerable pangolin, there must be greater understanding of how and where the pangolin meat supply chain operates in Asia.

Beyond the Scales: Pangolin Meat Trade in Asia #

Recent reporting on the COVID-19 (coronavirus) outbreak that originated in Wuhan, China suggests that the world’s most trafficked mammal – the pangolin – may have been the intermediate carrier of the virus from bats to humans. While experts continue to collect evidence and determine the epidemiology of the virus, China has banned the consumption of wild animals, which would include pangolins. The ban recognizes the link between the consumption of wild animals and the spread of novel diseases. However, for this ban to positively impact the vulnerable pangolin, there must be greater understanding of how and where the pangolin meat supply chain operates in Asia.

Scales of Justice #

Pangolin scales are made of keratin, like human fingernails, and are believed to carry curative properties in traditional medicine. Similar to pangolin scales, pangolin meat is trafficked for its alleged medicinal value, as well as a luxury food item. This demand is pushing pangolins towards extinction, and in response to this threat, CITES up listed all eight species of pangolins to Appendix I in 2016, prohibiting the international trade of the species.

Much of the discussion around the pangolin’s threatened status has been centered on the sheer magnitude of pangolin scales trafficked annually to destination markets, mostly in Asia. This focus is well-deserved: over the past five years, C4ADS has tracked a steady increase in the number of seizures of pangolin scales globally. While the significance of pangolin scale trafficking cannot be overlooked, it is also critical to consider the size of the illicit trade in pangolin meat. Without also understanding the pangolin meat trade in Asia, the illicit trade cannot be holistically addressed even with targeted actions such as the ban on wild meat trade in China.

By the Numbers #

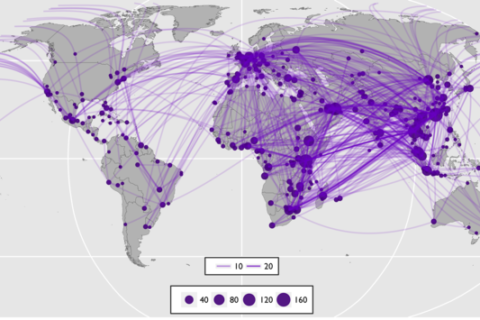

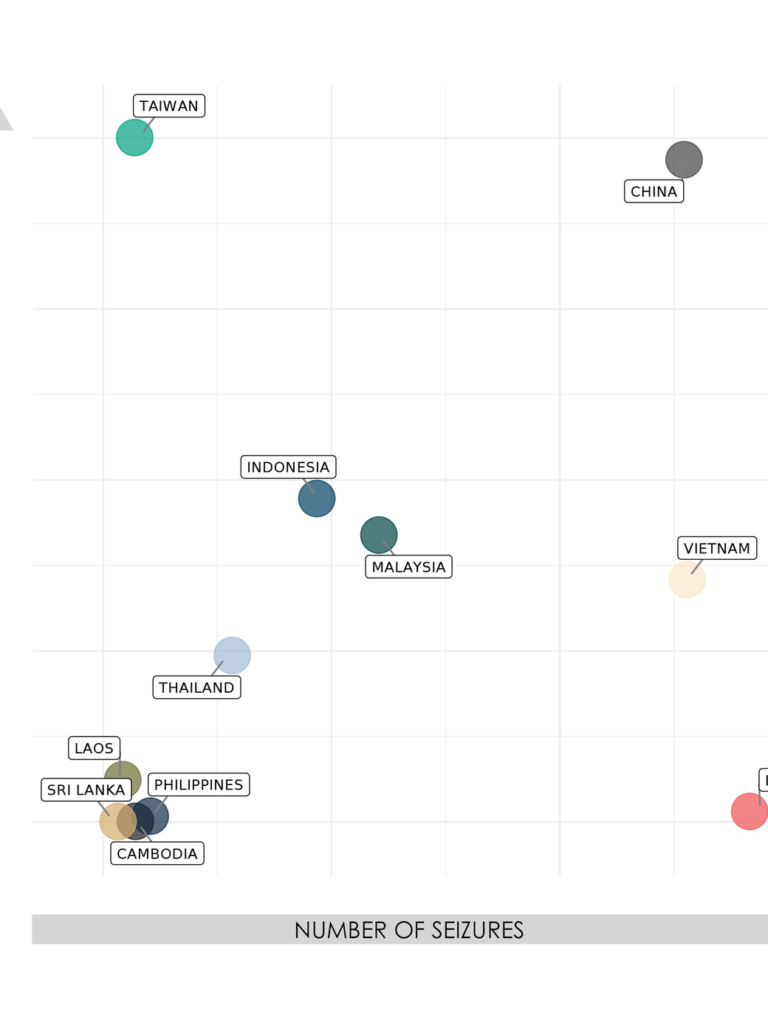

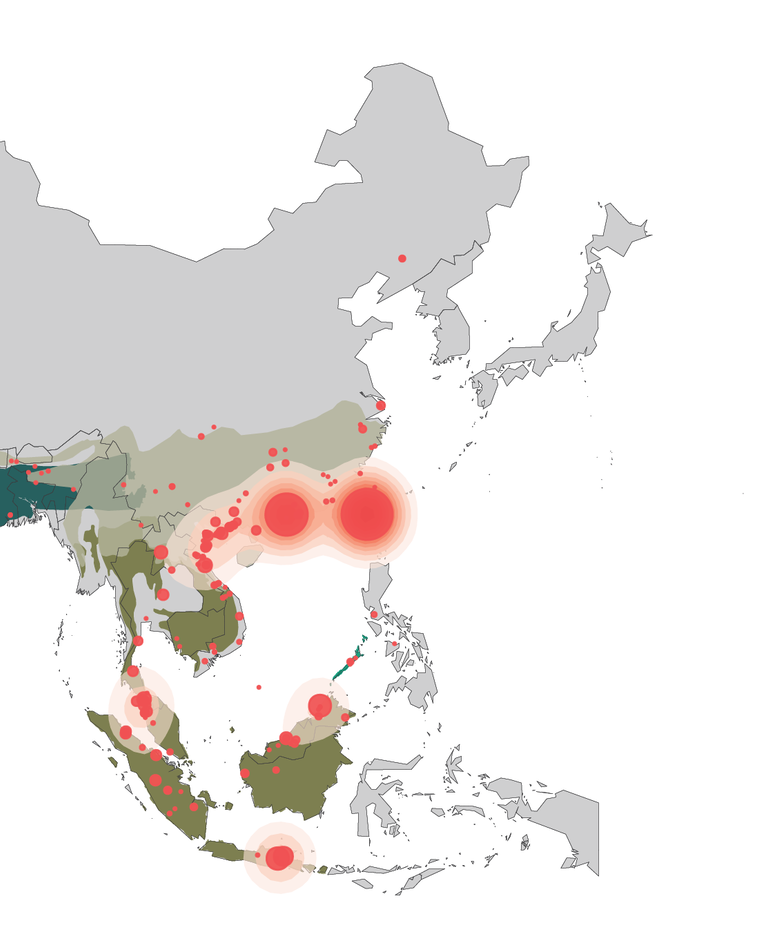

In the last five years alone, the C4ADS Wildlife Seizure Database has recorded seizures of over 14,000 live or dead pangolins that have been intercepted globally. This figure only reflects the known number of whole pangolins seized, and does not account for the number of animals poached and shorn of their scales for trafficking, or seizures where the quantity of pangolins recovered is not reported. Of these 14,000 pangolins, 99% were seized in Asia. While pangolin seizures are widespread across the Asian continent, China, India, and Vietnam account for the majority of them at 25%, 23%, and 22%, respectively.

Compared to pangolin scales, whole pangolins, live or dead, are more complicated for trafficking networks to transport to market. Pangolins survive on a supply of ants and termites gathered through foraging. While some Asian species of pangolin have been known to consume an artificial diet, pangolins often struggle to survive in a captive environment. Therefore, seizures of live pangolins are generally indicative of recent poaching activity. Dead pangolins require proper storage to preserve the quality of the meat and therefore are often seized frozen or recently-deceased alongside live pangolins. Maintaining product quality requires immediate transportation to the consumer, explaining why 90% of live and dead pangolin seizures in Asia are land seizures, often from buses and vehicles.

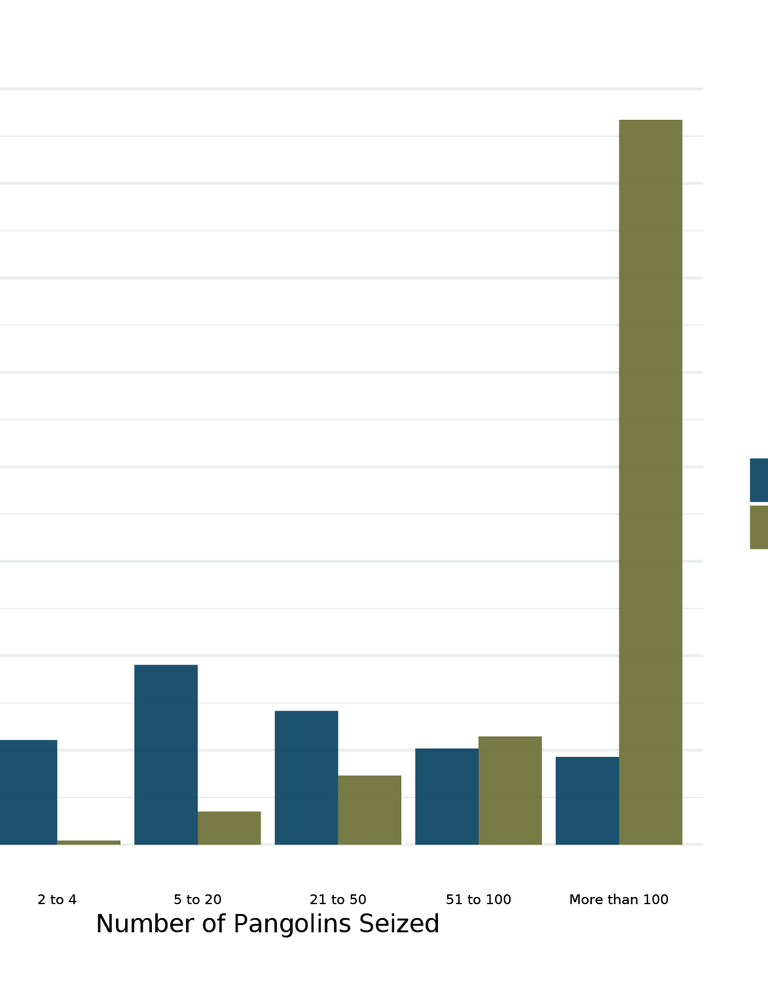

The short distances between poaching activity and consumers of pangolin meat in Asia and the intricacies of operating at-scale often lead to the assumption that the trade is run by informal networks. However, seizure characteristics indicate that this is not the case with pangolin meat. The C4ADS Wildlife Seizure Database reveals that large-scale seizures of whole (live or dead) pangolins account for a majority of the pangolin meat traded in Asia. Despite the fact that 57% of whole pangolin seizures are small-scale (resulting in the interception of one to 20 pangolins), 95% of the over 14,000 known trafficked pangolins were intercepted in large-quantity seizures (21 or more pangolins together). The capability to consolidate and transport large numbers of pangolins at one time points to the involvement of sophisticated, high-capacity networks of poachers, buyers, and transporters, similar to what is seen in networks trafficking ivory, pangolin scales, and rhino horn internationally.

At markets, pangolins, like other wild animals, can become potential vectors for the spread of infectious diseases. While pangolin scales elicit international attention, pangolin meat is a significant component of this illicit trade, and a potential catalyst of the current international coronavirus outbreak. Understanding the complexity of the pangolin meat trade may prompt new solutions that protect the species and global public health. In 2019, China made a public effort to reduce the demand of pangolin scales, specifically by not allowing Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) containing pangolin scales to be covered by its national insurance program. Meanwhile, the trade in pangolin meat took a backseat to such progress; pangolin meat continued to be sold in markets until the recent ban was announced as a result of the coronavirus outbreak. Tracking seizures of live or dead pangolin will be an important proxy for determining the effect of the new ban on the pangolin meat trade and whether there will be any real impact on the coordinated networks of illicit actors that profit from it.